Will the European Parliament elections have an impact on the EU’s enlargement agenda?

Polls predict that the next European Parliament (EP) will shift towards the right of the political spectrum after the elections. While the traditional European political centre is expected to hold, this new reality will likely have an impact on EU policymaking. Since this vote is taking place in an era of geopolitical shifts, one of the key questions will be the foreign policy implications of the elections, including the EU’s enlargement agenda.

According to the latest polls, more than 25% of the members of the next European Parliament will sit further to the right of the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP). The two parties on that side of the political spectrum, Identity and Democracy (ID) and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), could also become the fourth and fifth largest groups, respectively. The balance of power between the ECR and the ID groups will hinge significantly on whether Victor Orbán’s Fidesz chooses to align with one of the groups or remain non-attached.

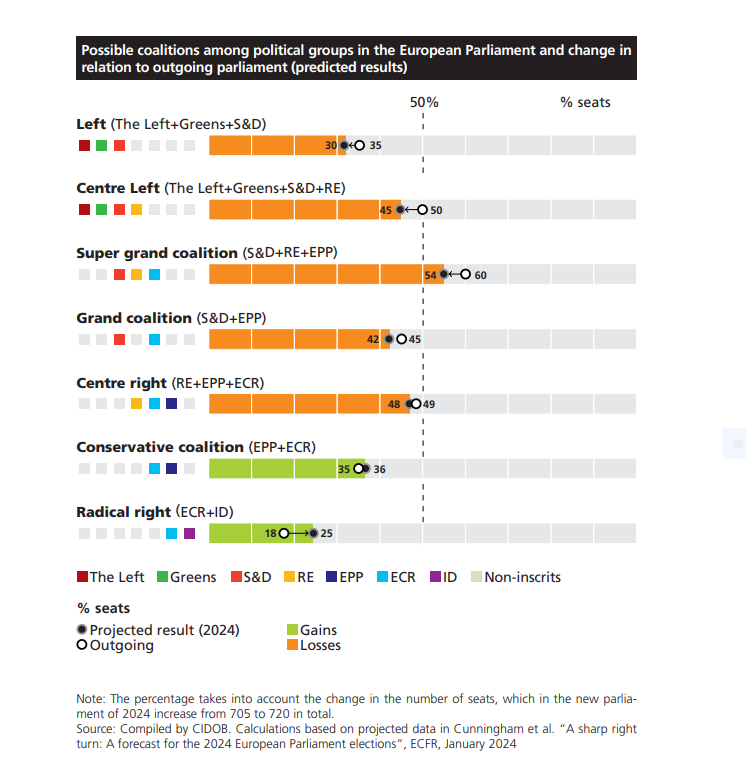

The pro-European “super grand coalition”, consisting of the conservative EPP, the social democrat S&D and the liberal Renew groups (plus the Greens/EFA, sometimes), will still have sufficient seats. Majorities could still be found without the support of the radical right parties, but things will be tighter as this coalition is projected to lose seats and only hold slightly over 50%. Indeed, the bigger the presence of ID and the ECR, the less space there will be for the centrist parties to build majorities.

The EPP will also be tempted to look to its right to seek partners on issues close to its conservative agenda, such as economic and monetary affairs, as well as the internal market or migration. For the first time, the possibility is emerging of a right-wing coalition, comprising the EPP, ECR and ID, and potentially supplemented by non-attached MEPs, predominantly from the extreme right. All this will place the EPP in a powerful agenda-setting position and move the EP further to the right. Before exploring the possible impact of the extreme right, it is essential to understand the role the EP plays in the EU’s external relations.

The EP’s role in EU foreign, security and enlargement policies

In the EU’s institutional set-up, member states have the competence when it comes to foreign and security policy, but this does not leave the EP powerless. The EP possesses three key competences, all of which extend to enlargement policy.

First, the EP possesses supervisory and deliberative powers. This competence is vital, as it influences the discourse on foreign policy. A noticeable shift towards the right within the European Parliament could lead to changes in foreign policy debates and recommendations aligned with the positions and priorities of radical right political parties, including on enlargement.

Secondly, the EP plays a significant role in the law-making and law-shaping process in the external action domain when it comes to the negotiation and ratification of international agreements. The parliament’s consent is required for any new accession to the EU.

Lastly, the European Parliament has budgetary powers. Through them, the parliament holds significant influence over the financial aspects of accession, allowing the institution to directly shape the allocations for the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance and other types of resources assigned to candidate countries, starting with Ukraine. This gives the EP a final say in the budget debate, which is core in terms of defining foreign policy priorities and implementing them.

Any potential shift towards the right in the EP elections would impact the future of European legislation, the EU budget, and, more specifically, the EU’s enlargement policy moving forward.

How does the radical right deal with enlargement?

Radical right parties in Europe share a strong ethnonationalist orientation. They often insist on the primacy of national sovereignty over EU laws and EU foreign policy. Some of them are also sceptical of regional and global institutions and norms. There are certainly different levels of radicalism in radical right parties in their opposition to the European project, and national narratives and interests among radical right parties are often discordant.

Until now, radical right fragmentation in the European Parliament and the united stance of the mainstream parties on external affairs have reduced the overall impact of the extreme right on EU’s foreign policy. The divisions have also hampered radical right parties’ ability to present a unified stance on key policy areas, including enlargement. Yet, while these parties have had a modest impact on the decisions, they shine when framing EU foreign policy debates. The polarisation and securitisation of EU foreign policy is a common feature of the radical right.

Radical right parties often oppose further EU enlargement. The main exception to this is when the inclusion of a specific new member favours particular national interests. The overall radical right perception of further EU enlargement is that it is too costly in terms of national sovereignty concessions and economic efforts and that it will lead to “undesired” migration flows. However, radical right parties also vary in their hostility towards further EU expansion.

Some European radical right parties oppose EU enlargement because of socio-economic considerations. The Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), for instance, argues that enlarging the EU could jeopardise the EU’s political and economic stability. New EU member states would draw considerable funds from the EU budget while making only small contributions to it given the size of their economies. Moreover, the FPÖ rejects using the EU budget to finance further enlargement as it sees that this approach would erode member states’ sovereignty.

France’s Rassemblement National (National Rally; RN) also cites socio-economic reasons for its opposition to enlargement. It argues that this process would bring a large increase in immigrants, who would compromise the security, well-being and job opportunities of French citizens. Likewise, the Sweden Democrats (SD) question the EU’s ability to integrate more members and the new members’ capacity to protect their borders from cross-border organised crime.

The second major rationale against further EU enlargement among European radical right parties is closely related to their focus on domestic policies. They claim that an enlarged EU will threaten member states’ sovereignty. This is the case for the French RN, which rejects enlargement on the grounds that it is contrary to the will of the European people and that it jeopardises member states’ interests. The Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) and Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany; AfD), both Eurosceptic parties, go even further and claim that EU policies pose a threat to their respective domestic affairs. Enlargement for them is no different.

A third approach against further EU enlargement can be found in Finland’s Perussuomalaiset (the Finns Party). Their opposition to expanding the EU springs from their perception that this process is not consistent with the reasoning behind it. EU enlargement is now seen as a geopolitical response to the imperatives of the current security landscape. The Finns Party argues that the EU is not a relevant geopolitical actor and that the union is incapable of providing security to their country, and that, therefore, enlargement is not a geopolitical answer to security challenges.

Nonetheless, not all radical right parties oppose further EU enlargement so firmly. For instance, while the Polish party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice; PiS) highlights the importance of maintaining Poland’s sovereignty, it also supports enlargement and EU-aided democratic reforms in the EU’s neighbouring countries. PiS endorses the transformative power of EU enlargement and its contribution to the stability, prosperity and security of the continent.

Then, there is also a transactional and opportunistic approach to EU enlargement among European radical right parties. Some will support enlargement if they see that political benefits can be extracted from it. This is the case of the Romanian party Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor (Alliance for the Union of Romanians; AUR). It supports the integration of neighbouring countries in exchange for an EU reform that increases member states’ sovereignty.

It is also the case of the Hungarian party, Fidesz. Hungary has traditionally been a supporter of enlargement, particularly to the Western Balkan countries, where Hungary has significant political and economic interests. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has close connections with illiberal leaders in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Hungary’s endeavours to extend its influence in the Western Balkans have served to advance Orbán’s political and economic agenda. This rapprochement has proven to be detrimental to the democratic centrality of the enlargement process and, therefore, to the EU’s enlargement strategy.

How will the results of the elections impact EU enlargement policy?

While the EP is arguably not the most decisive institution when it comes to EU foreign policy and enlargement, it still has powers that might have an impact. An increase in radical right representation could complicate the parliamentary approval process for accession treaties, enhanced financial assistance for enlargement-related reforms and the importance given to the rule of law within and outside the EU.

A rightward shift in the EP is likely to frame the necessary debate on EU enlargement in polarising and securitised terms. In doing so, radical right parties will try to shape the enlargement debate according to their own perspectives while disregarding the intrinsic transformative power of the EU’s enlargement policy. Moreover, centrist parties might be tempted to adopt more extreme positions, regarding enlargement too, due to growing electoral competition with the radical right. The consequences of this shift may hamper the EP’s ability to form coalitions to move forward.

Furthermore, increased representation of the radical right in the EP will potentially undermine the EU’s cohesion and credibility as a liberal democratic project. This would therefore reduce the possibilities of enlargement being a transformative tool, as candidate countries may not find the core values that made them seek EU membership in the first place.

Last but not least, although the European Council is the key institution for EU enlargement, the EP elections will provide a first glimpse of the challenges that the European Council may face in the near future. If this current political trend is not reversed, increased representation for the radical right in the European Council (determined by national elections) will pose even deeper challenges to the enlargement policy moving forward.

Radical right parties can be expected to deploy a transactional approach to further EU enlargement through national vetoes. Blocking consensus-building on enlargement in the European Council may become more frequent when national interests kick in and some sort of political or economic benefit can be obtained. This will diminish the EU’s potential to move forward with further enlargements.

In conclusion, the prospective shift to the right side of the political spectrum in the upcoming EP elections could impact the future of EU enlargement policy. While the mainstream “super grand coalition” is forecast to hold, the coalition’s solidity is expected to diminish.

Even if radical right parties in the EP do not have a unified approach to EU foreign policy, they have generally opposed EU enlargement for three main reasons: the socio-economic costs of enlargement and the division of its burdens within the EU; the interpretation that enlargement is a threat to national sovereignty; and the perception that adding new members to the EU does not fulfil enlargement’s purpose of enhancing peace, prosperity and security on the European continent.

Worryingly, an increased presence of the radical right in the EP could contribute to eroding the EU’s cohesion and credibility as a liberal democratic entity on the continent and around the world. Furthermore, the upcoming EP elections will offer insights into the potential challenges awaiting the European Council. At the end of the day, the European Union’s overall political landscape will be reflected in different institutions and impact policy-making.

CIDOB Monographs -88- 2024

P 19-23. ISBN:978-84-18977-22-0