After the elections: more or less Europe?

The story of European construction is one of a gradual transfer of national sovereignty to a supranational entity. But this process of integration has happened in fits and starts, and moments of crisis have raised questions about the logic of an ever closer union. Still, many of these crises have resulted in further integration (Schimmelfennig, 2024). In practice, the transfer of sovereignty has allowed the Europeans to address common challenges in an increasingly competitive world as a bloc. On their own, the member states would not have the same capacity to assert their interests and mould the world according to their rules. As the saying goes, there are only two types of country in Europe: small countries and small countries that have not yet realised they are small.

But the elections to the European Parliament in June may mark a break with this integrating logic; not as a consequence of a crisis (in democracy, voting is never a crisis), but because the political forces that will be regarded as winners are reluctant to continue committing to the transfer of powers. And because they do not agree with the logic of supranational cooperation as a guiding principle of the European Union (EU).

Brussels, the capital of Europe (and go-to scapegoat for the problems of the member states, as if they had no hand in the decisions that are taken there), has become the symbol of an EU perceived as a regulatory behemoth over the course of its 70-year history. And certain political forces, which have sworn enmity to this image of Brussels (Enzensberger, 2014), could be bolstered at the ballot boxes in the upcoming European elections in June.

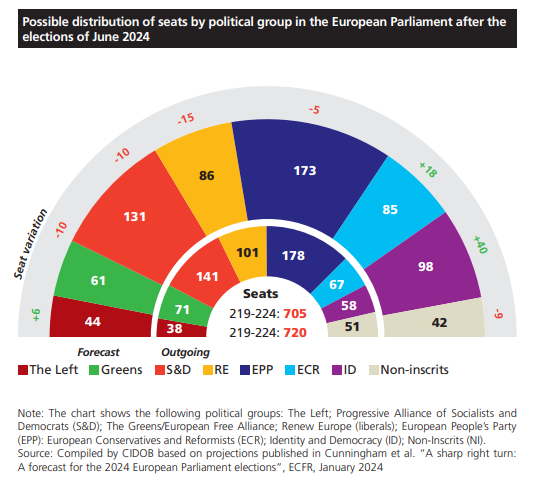

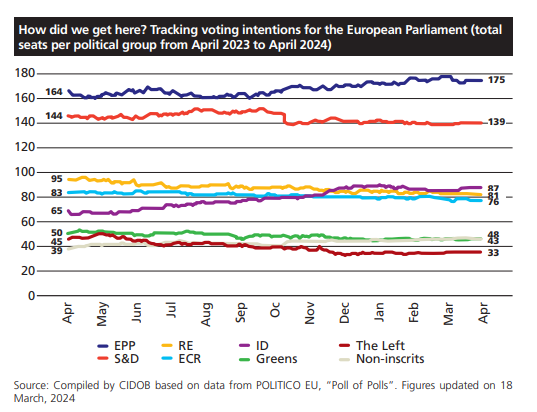

The polls show the two parliamentary groups on the radical and extreme right obtaining the best results, relatively speaking, even aiming at record shares of the vote. According to these election surveys, Identity and Democracy (ID) could be the third-largest group in the European Parliament for the first time in its history; and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) would vie for fourth place with the liberals. With these results, the very idea of the EU and the way it functions would be at risk.

Transfer or recovery of sovereignty?

The question of how much sovereignty the member states must retain or recover from the EU and how much must continue to be transferred to the EU institutions is a fault line between political families. Moving from left to right across the spectrum, below are the views of the European political parties and groups.

The Party of the European Left (PEL), which encompasses the radical left parties, is not averse to transferring more sovereignty to the EU, even if the group does call for a different kind of union. In its manifesto it advocates extending the EU’s powers in sensitive areas such as taxation and regulation of artificial intelligence (AI). Other proposals include a permanent investment mechanism or an EU regulation on labour rights. The European Left invokes the conclusions of the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE) regarding a revision of the treaties to secure a more democratic, transparent union that is accountable and socially cohesive. It even calls for granting the European Parliament the right to initiate legislation.

The Greens’ election manifesto, for its part, argues that the European Union is the key level for climate and environmental policy. They want a democratic, feminist Europe that safeguards human rights and that is why they too demand a different EU: a federal Europe with enhanced powers. The Greens also cite the CoFoE as a source of legitimacy.

The Party of European Socialists (PES) defends the need to enhance EU powers and refers to this in the first point of its manifesto when it calls for full implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights or a strengthened European Labour Authority. Other proposals from this group that would include the transfer of more powers are a permanent European investment capacity or increasing EU support for member states to combat unemployment. The political forces from the PES family back enlargement and to that end champion a reform of the EU, with targeted treaty changes that empower the parliament and the commission. There is no specific mention, however, of granting the European Parliament the right to initiate legislation or of a total reform of the treaties, nor do they look to the CoFoE as a source of legitimacy.

The political parties gathered under the umbrella of Renew, as the liberal group in the European Parliament came to be known after the elections of 2019, have set out their position via the manifesto of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), the party to which most of the Renew forces belong. The liberals’ manifesto includes the need to reform the EU in line with the conclusions of the CoFoE. They call for revisiting the treaties and transforming the European Commission into a true political leadership body, as well as the introduction of transnational voting lists.

For its part, the European People’s Party (EPP) presents itself as a “bridge” between those who consider themselves “global citizens without roots” and those who want to retreat into “national egoism”. Its manifesto makes constant appeals to the EU motto of “United in diversity” to stake its claim to the role. The EPP says the parties to its left (Socialists, Greens and liberals) have lost sight of the big picture in the project of European construction at times; but it makes a distinction between them and the populist parties on the right, who it directly accuses of wanting to destroy Europe today. The EPP champions a strong and effective EU. But the conservatives do a balancing act when it comes to the dilemma of kicking on towards an ever closer union or restoring powers to the member states. They make no mention of the CoFoE but acknowledge that the EU must improve its institutions if it is to be capable of acting in a more efficient, strong and democratic manner. At the same time, they defend revising which powers could be transferred back to the member states, in a nod to the parties of the ECR. To that end, they propose a new European Convention to potentially improve the treaties.

In their Prague Declaration (2013), the European Conservatives and Reformists already championed the importance of the integrity of national sovereignty in the face of EU federalism and of putting an end to the waste and excessive bureaucracy of all things EU. A decade later, in the Reykjavik Declaration (2023), the parties of this radical right alliance said that the Europe they believe in is a union of “independent nations” that, though they cooperate, “retain their identity and integrity”. In other words, they would rather the exercise of power lies with the states than with any supranational authority. Its manifesto for the elections builds on the same idea that state sovereignty must be safeguarded and there is no room for “unnecessary centralisation of power in Brussels”. This means that cooperation in Europe is best when it takes place between sovereign states rather than in the framework of a supranational authority to which powers have been delegated.

Identity and Democracy dispensed with adopting a manifesto for the elections of June 2024. At the party’s meeting in November last year, Marine Le Pen declared the EU is a recent, artificial and ideological creation compared to a Europe of nations that has existed for thousands of years. In the Declaration of Antwerp (2022), the closest thing to an electoral programme, the ID parties level the criticism that, since Brexit, there has been an acceleration of efforts within the EU to replace the member states with a unitary state. And they accuse the bloc of seizing every crisis to advance its plan of more integration. In view of this, ID is opposed to any future transfer of sovereignty, arguing that the only cooperation among nations they are ready to accept is that in which the peoples and member states retain their rights. And they call for the return of powers to the states.

The subject of which specific powers could be restored to the member states, and under what conditions, is unlikely to come under discussion during the election campaign. Instead, it is more probable that the parties in favour of continuing European integration – each with its own nuances – will accuse those who are not of wanting to torpedo the union by trying to subvert its purpose of supranational cooperation, as the Socialists, EPP, Left and Greens do. The parties on the radical right and national conservatives that make up the ECR and ID, meanwhile, will counter by declaring they are patriots and will level accusations of “cultural Marxism” and globalism, backed by a transatlantic “national conservative” front that appears to have made Budapest its new mecca (The Economist, 2024).

Division or pragmatism to the right of the EPP?

Support, or lack thereof, for European integration forms a deep fault line between European parliamentary groups and parties. On the whole, the forces that sit on the ECR and ID benches are loath to continue relinquishing national sovereignty to a supranational entity that they believe wants to stifle states’ individuality. Yet there are differences between the two groups, as well as in the perception that the majority families in the European Parliament have of them. The EPP’s relations with Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, in her role of pragmatic Atlanticist, are testimony to that.

The EPP is performing a balancing act by courting the European Conservatives and Reformists but in turn rejecting the forces it describes as “Putin’s friends”, in the words of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. The polls say the current head of the EU’s executive branch could need the support of Meloni and the political family she leads to secure a second term. Perhaps that is why Von der Leyen visited Italy several times in the closing stages of her first term; she travelled to Tunisia in the company of Meloni (and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte) to close a deal under the “Team Europe” formula that helped to stem the arrival of migrants on Italian shores, and she has adopted certain points of the Italian prime minister’s discourse. Von der Leyen has “Melonised” (de Benedetti, 2023) and in turn the ECR has also opted to move closer to the EPP (Pascale and Griera, 2023) in a bid to gain more clout and forge alliances on a European level. It is a strategy that the EPP leader, Manfred Webber, already espoused ahead of the Italian elections in 2022 (Sánchez Margalef, 2022). The ECR parties have dropped the idea of leaving the EU because they reap substantial rewards from belonging to the union, such as funds. And they have bolstered their narrative of reliable partners in votes on foreign and security policy matters in the European Parliament (Becker and Von Ondarza, 2024) on particularly sensitive issues in the current context, like the war in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, according to Becker and Von Ondarza (2024), the “Putin’s friends” that Von der Leyen alluded to would be the parties that make up ID. These political forces too have dialled down their inclination to exit the EU, partly out of electoral interests, but they still display varying degrees of Eurosceptic vehemence in their rhetoric. While National Rally, Marine Len Pen’s party, specifically omitted the option of leaving the EU in its domestic electoral programme in 2022 because it could have cost it votes (Wright, 2022), Alternative for Germany has been more explicit in pursuing the Brexit model (Chazan, 2024) without seeing its short-term chances of wielding influence harmed in any way.

Will polarisation halt integration?

If the election results are as the polls are predicting, the new European Parliament will be more belligerent over the transfer of powers. European integration could therefore experience a sudden slowdown and, potentially, grind to a halt altogether. The European People’s Party group will hold the key. If ECR and ID gain greater sway over EPP decision-making, the Christian Democrats will be obliged to take a stand on whether they remain a force for an ever closer union or they act as a blocking minority on certain issues with the groups to their right.

There are two effects worth noting as we head into a new political cycle. First, this scenario in the European Parliament does not bode well for major steps towards greater European integration. And only in the event of an external crisis could the urgency of the situation act as a catalyst for further transfer of new powers to the EU, such as on issues of defence and taxation, for example.

Second, polarisation in the European Parliament is set to increase and this will likely lead to greater politicisation of European affairs and push the parties to be more confrontational in setting out their vision for the EU. If the central bloc (EPP, PES and liberals) disappeared, or was clearly weakened, we could also see an alternative political bloc scenario emerge on the left (PES, Greens and Left) and right (EPP, ECR and ID), with the liberals holding the balance of power. That could lead to new political dynamics both inside the parliament and in interinstitutional disputes.

Still, European integration is not decided in the Parliament alone. The Council of the EU remains largely dominated by parties from the central bloc. Even if representatives of ID took office as heads of state or government in the future, consensus will remain the norm rather than the exception. What changes is the capacity to undermine the institutions and the European project.

References

Becker, Max and von Ondarza, Nicolai (2024). “Geostrategy from the Far Right”, SWP Comment 2024/C 08. doi:10.18449/2024C08. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/geostrategy-from-the-far-right

De Benedetti, Francesca (2023). “Ursula von der Leyen Is Taking Europe to the Right”, The Jacobin. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://jacobin.com/2023/09/ursula-von-der-leyen-state-of-the-union-far-right-centralization-giorgia-meloni-european-commission

Chazan, Guy. “German far-right leader hails Brexit as ‘model for Germany’”, Financial Times, January 22nd, 2024. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://www.ft.com/content/5050571e-79f9-4cb7-991c-093702ec8833

Enzensberger, Hans Magnus (2014). El gentil monstruo de Bruselas o Europa bajo tutela, Barcelona: Anagrama.

Pascale, Federica and Griera, Max. “Spain’s possible ‘Melonisation’ strengthens ‘patriots’ EU plans”, Euractiv, June 2nd, 2023. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/spains-possible-melonisation-strengthens-patriots-eu-plans/

Sánchez Margalef, Héctor. “Elecciones en Italia: ‘¿Alea iacta est?’”, Revista 5W, September 24th, 2022. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://www.revista5w.com/temas/poder/elecciones-en-italia-alea-iacta-est-68317

Schimmelfenning, Frank (2024). “Crisis and polity formation in the European Union”, Journal of European Public Policy. DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2024.2313107.

The Economist. “Nationalists of the world, unite!”, The Economist Briefing, February 14th, 2024. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://www.economist.com/briefing/2024/02/15/national-conservatives-are-forging-a-global-front-against-liberalism

Wright, Georgina (2022). “What a Marine Le Pen Victory Would Mean for Europe”, Institute Montaigne. [Accessed 12.03.24] https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/what-marine-le-pen-victory-would-mean-europe

CIDOB Monographs -88- 2024

P. 11-17 ISBN:978-84-18977-22-0