India and Pakistan as the pivot of China’s South Asia strategy

Critical to understanding China’s rise in South Asia is an appreciation of the dynamics of competition between Beijing and Delhi, and the geostrategic relationship between China and Pakistan. Indeed, the growing rivalry between China and India has an impact on the domestic and foreign policies of the other countries in the region, which face pressure to find a balance between their economic and development interests and their geostrategic concerns.

There has been a shift in China’s perception of South Asia over the last decade. From being considered peripheral and of little relevance to Beijing, the region comprising Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka has moved up its list of foreign policy priorities. China shares a border with five of these countries, namely Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan. But the key factor that explains Chinese interest in this subregion of Asia is its contest with India and its strategic relationship with Pakistan, whose support is vital to counter Delhi’s hegemonic position in South Asia. The fact that these three countries are also in possession of nuclear weapons adds a disturbing element to the dynamics of competition among them.

Regional trends in South Asia are marked by the dysfunction arising from the confrontation between India and Pakistan; the lack of economic integration among the countries in the region; and structural limitations (like the absence of connecting infrastructure or barriers to trade); as well as changes in governments’ foreign policies with each new election cycle. The Chinese government has capitalised on these failings as it has drawn closer to the region. Indeed, Beijing engages with South Asia mainly through economic measures and trade, and the primary instrument is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Under this approach, Beijing proposes improving the various countries’ investments, trade development and connectivity with China (not so much among one another), in turn trying to isolate India from its neighbours. Furthermore, it has diversified the channels through which it engages with the countries of the region over the last few years, however, adding security, political and cultural facets to its interaction. Prominent among these instruments are arms sales and military cooperation with Pakistan and Bangladesh (the world’s biggest buyers of Chinese weapons); China’s role as a mediator in the Istanbul Process for peace in Afghanistan between 2014 and 2022, and between Bangladesh and Myanmar following the Rohingya crisis in 2017 (Legarda, 2018); or the opening of Confucius Institutes in the region, which has 15 of these centres.

The political and economic dynamics of South Asia also reflect the impacts of Sino-Indian competition, as every country feels the pressure of such rivalry. Although China’s presence in the region is a relatively recent phenomenon, the role of India is crucial. Delhi is obliged to juggle its ambitions of greater global clout with being careful not to alienate China too much, while maintaining the edge in its backyard, where it preserves political, economic and cultural primacy in varying degrees of intensity. However, India sees the launch of the BRI maritime route as a ‘string of pearls’ with which its rival is looking to restrict or control its access to the sea through the construction or control of surrounding ports, including Chittagong and Payra in Bangladesh, Hambantota and Colombo in Sri Lanka, and Karachi and Gwadar in Pakistan (Faridi, 2021). Delhi’s concern over China’s interest in dominating its sphere of influence by bringing pressure to bear on small countries is no trivial matter. Every country in the area, regardless of its size, faces pressure to turn towards one power or the other.

Dictating a new regional order: India’s perception of China

Since the change of focus towards a foreign policy that prioritises a stable neighbourhood, the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, has pushed the idea of creating a “community with a shared future”, based on the principles of friendship, sincerity and mutual benefit, in a bid to create an image of China as a benevolent actor (Garver, 2012). But Delhi rejects that rhetoric, as it eyes China’s growing presence in the region with suspicion and is mindful of the contradiction between the words of its neighbour to the north and its actions.

Contrary to the official discourse, Beijing has shown limited interest in defining the demarcation of over 3,400 km of border with India, the only country other than Bhutan in this situation. It is no coincidence that neither is a member of the BRI. In Delhi’s view, China reignites the border tensions periodically to throw it off-balance and shape South Asia, as shown by the crisis active since 2020 in the Galwan Valley on the Himalayas border, following a deadly brawl between Chinese and Indian troops. In India they believe that Beijing considers the country inferior, and as such it must never be on an equal footing in the global hierarchy (Menon, 2021).

China, meanwhile, calls on India to end its conflict with Pakistan and develop their economic and political potential together, accommodating the rise of Beijing in the region. But in the growing competition in the Indo-Pacific, where India is better placed, China sees Pakistan as a longstanding ally and a strategic partner that plays a key role in the zone, one that can be relied on to promote a new order. Pakistan, for its part, tries to thwart Indian leadership in the subcontinent, as well as Delhi’s aspirations to be a global actor, by using strategies of attrition and destabilisation along the Line of Control – the boundary separating it from India – employing non-state actors (like the extremist groups Jaish-e-Mohammad and Lashkar-e-Taiba) to rock India’s domestic stability and divert its attention away from economic development. Bearing in mind Pakistan’s importance for Beijing, these two fronts discourage any cooperation on the part of Delhi.

In the face of China’s growing assertiveness, India has felt compelled to seek alternatives to preserve its leadership in the region, including drawing closer to Washington, as it prioritises evening up the balance of forces alongside other powers, aware still of the asymmetry in relation to China. Without altering its preference for creating partnerships rather than alliances, India has come to the conclusion that its previous policy of appeasement towards China failed to temper its neighbour’s conduct. If Beijing was looking to turn it away from the United States, then, it has achieved the exact opposite. India’s membership of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, along with the United States, Japan and Australia, illustrates Delhi’s desire to invite and obtain greater involvement of other actors in the Indian Ocean that help to check China’s ambitions. It is, then, a strategy to manage China’s presence rather than outright opposition, which differentiates India’s view from that of Washington.

Pakistan and the BRI’s success as a foreign policy instrument

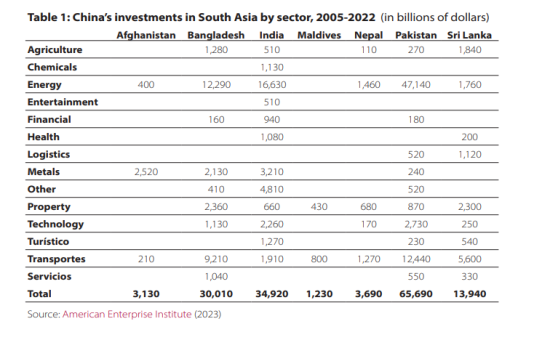

China-Pakistan relations have been framed as an “all-weather friendship” for decades, but this bond has grown stronger over the last few years, propelled by India and the United States moving closer, deteriorating relations between Washington and Islamabad and, above all, Pakistan’s central place in the BRI. Islamabad is the biggest BRI investment recipient thanks to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), launched in 2015. It was the beneficiary of over $65bn between 2005 and 2022.1 In fact, the CPEC is the flagship BRI project and aims to connect the port of Gwadar in the western province of Balochistan – an undertaking that began in 2006 – with the Chinese province of Xinjiang, as well as develop multiple energy and transport initiatives. Once finished, it would give China direct access to the Indian Ocean, allowing the Asian giant to avoid the Strait of Malacca, through which 70% of its energy imports transit. For Beijing, the BRI’s legitimacy hangs on the success of this corridor, touted as the deal of the century.

The project has run into obstacles, however. Pakistan is mired in political instability and on the brink of economic collapse, a situation exacerbated by the floods in the summer of 2022 that left a third of the territory under water and damaged a large part of the infrastructure already built. These domestic difficulties have stalled the progress of the CPEC. As the Wilson Center expert Michael Kugelman stated, “the reality on the ground is that Pakistan has been slow to complete infrastructure projects and China has been slow to fund new ones”. Given Pakistan’s importance, and in order to prevent defaults hitting Chinese firms in the light of the country’s debt servicing difficulties, China has come to its financial rescue on numerous occasions through state-owned banks and enterprises. Since 2013, that also includes the use of People’s Bank of China liquidity lines2. In 2022, for example, China extended a loan to the value of €2.18bn. In total, Pakistan has run up rescue loans to the value of 9.5% of its GDP and is the world’s biggest recipient of financial assistance from China. Trade only accentuates that dependence. Nearly a quarter of Pakistan’s imports come from the Asian power.

China’s major presence in Pakistan, however, is facing a growing security threat on account of the existence of insurgent groups that are hostile to its projects, particularly in Balochistan. This western province, which has a long history of opposition to the central government, sees China’s presence with distrust, both because of the extractivism it promotes and because of the political and economic exclusion of the Baloch people from the planning and execution of projects instigated by a centralist Islamabad. The perception that the execution of certain investments (particularly infrastructure ventures carried out directly by Chinese companies) do not benefit the local population, as well as Chinese interference in Pakistani politics, generates a hostile environment in the shape of attacks and acts of sabotage on Chinese projects or workers. A suicide bombing in April 2022 claimed the lives of three Confucius Institute staff at the University of Karachi. At present, the Pakistani military establishment has most interest in maintaining good relations with China, given that many of its companies are profiting from CPEC contracts.

However, the increase in terrorist attacks on Chinese nationals and the links between Islamist militants in Xinjiang and Pakistani terrorist groups – a concern that extends to the situation in Afghanistan and the prospect of regional instability – have raised Beijing’s reservations about its partner. But it has little bearing on the strategic view that China has of Islamabad or on its readiness to prop the country up. Ultimately, against a backdrop of greater competition in the region, Beijing is backing Pakistan, even if the doubts among China’s elites over continued investment may increase if the instability persists.

Echoes of Sino-Indian rivalry in other countries in the region

In 2017, Indian analyst Brahma Chellaney coined the term “debt trap diplomacy” after Sri Lanka surrendered control of the port of Hambantota to China over a supposed loan default. The writer’s description holds that Chinese diplomacy rests on the coercive use of geostrategic economic instruments whereby countries take on debt they cannot service and Beijing exploits the situation to secure a position of advantage, gain control of strategic infrastructure and increase its influence over these countries. The idea serves to discredit China’s action in the neighbourhood, which India views as interference. While the Sri Lanka argument has been since been rebutted3, the idea has taken hold in the perceptions and imaginations of leaders across the world, tarnishing China’s BRI action as a whole.

Despite India’s bid to demonise these economic interests among its neighbours, China is sometimes the only available option given the lack of economic opportunities from Delhi or the inability to meet the conditions imposed by international bodies. Other prominent examples of major beneficiaries of Chinese investment besides Sri Lanka are Bangladesh and Nepal, bearing in mind that Bhutan has not joined the BRI and the Maldives has cooled on the project because of domestic party interests and India’s influence. Bangladesh, for instance, is the country to have benefited most from the BRI in the region after Pakistan, with investment in excess of $26bn since 2014 (see appendix table 5). Dhaka’s success is also down to its ability to manoeuvre and tread a fine line not only between China and India – which has also invested and developed similar projects in the country – but with other powers like the United States or Japan, too.

Nepal, meanwhile, was one of the first countries to sign up to the BRI in a bid to diversify its dependence on India and attract connectivity and infrastructure projects, particularly after the devastating earthquakes of 2015. Many BRI-linked projects, however, have ground to a halt or are on ice – sometimes because of logistical issues, like the difficulty in executing projects in the Himalayas, other times out of lack of interest of the parties – tarnishing the initiative’s image in the region.

In addition, there is also the fear that Beijing’s economic sway will influence these countries’ domestic policies. Over the last few years, some political parties in Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal or Sri Lanka have reactivated (and exploited) the power dynamics between Beijing and Delhi to make political gains. In the Maldives, for example, the former president, Abdulla Yameen, who is in favour of a greater Chinese presence, campaigned in a T-shirt bearing the slogan “India Out”.Similarly, in Sri Lanka, China’s shadow pits the Rajapaksa clan, with their promises of China-sponsored economic development, against the president, Ranil Wickremesinghe, who is more inclined to remain neutral. The latter leader treads a delicate path between not opposing Beijing and moving closer to Delhi, particularly amid the current process of renegotiating Sri Lanka’s debt.

Finally, it is important to highlight that, while these countries have capitalised on the contest to reap gains from both China and India (and even from the United States), what concerns them is how these loans and Chinese infrastructures affect the functioning of their governments. The Chinese projects, which come with few conditions attached, contribute to local economic development. But sometimes other factors, like their poor quality, a lack of sustainability, scant profit sharing or debt pressure, make them less appealing. All the same, it is beyond question that China’s growing presence in South Asia has helped to reconfigure the political and economic order of a key region of the Indo-Pacific.

References

Chellaney, Brahma. “China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy” Project Syndicate, January 2017. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-one-belt-one-road-loans-debt-by-brahma-chellaney-2017-01

Faridi, Saeeduddin. “China's ports in the Indian Ocean”. Indian Council on Global Relations – Gateway House, 2021. https://www.gatewayhouse.in/chinas-ports-in-the-indian-ocean-region/

Garver, John W. “The Diplomacy of a Rising China in South Asia” Orbis, Summer 2012. https://www.chinacenter.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/diplomacy-of-a-rising-china-in-south-asia.pdf

Jones, Lee and Hameiri, Shahar. “Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt-trap Diplomacy’” Chatham House – Research Paper, 2020. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-08-25-debunking-myth-debt-trap-diplomacy-jones-hameiri.pdf

Kugelman, Michael. “Have China and Pakistan Hit a Roadblock?” Foreign Policy – South Asia Brief, 2023. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/09/china-pakistan-cpec-infrastructure-economy/

Legarda, Helena. “China as a conflict mediator: maintaining stability along the Belt and Road” MERICS, 2018. https://www.merics.org/en/comment/china-conflict-mediator

Menon, Shivshankar. India and Asian Geopolitics. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2021.

Notes:

1- See Appendix, Table 5.

2- For more information see the chapter by Víctor Burguete in this series.

3- In 2016, when Sri Lanka ceded control of the port of Hambantota to China for 99 years, the island nation’s debt was mostly in sovereign bonds, not in Chinese hands. Today, China accounts for 20% of the country’s total debt, compared to the 36.5% in sovereign bonds. The country’s macroeconomic situation was also exacerbated by a series of political decisions in the economic sphere – such as tax cuts – along with the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic, triggering an economic crisis caused by those same elites. See Jones & Hameiri (2020).