China’s bid for leadership in Southeast Asia

China has become a key player in the future of Southeast Asia. The country is looking to secure its economic, political and security interests the region in order to consolidate its status as a superpower. Relations between China and the Southeast Asian countries have improved considerably, but there is a lingering distrust of the Asian giant fuelled by its diplomatic influence in several countries and its growing military might, visible in the South China Sea.

China’s economic ascent has transformed the country’s role in the international system and consequently in one of its areas of greatest interest, Southeast Asia. It has a close terrestrial and maritime connection to the region – it shares a land border with Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam – and interaction has been intense down the centuries, as evidenced by the presence of a large Chinese diaspora scattered across the zone.

There has been a gradual shift in China’s relations with the eleven Southeast Asian nations over the last two decades, both on the mainland (Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore) and in the insular states (the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei and East Timor), brought on by a dual process of change. First, China’s ascent has made the country the Indo-Pacific’s main economy. And second, the profound transformation of its foreign policy has turned the Asian giant into an extremely assertive actor, with an agenda designed to maximise its position in the region. While China’s global relations have improved with time, there are still major pockets of distrust in Southeast Asia.

What does China want in Southeast Asia?

Deng Xiaoping’s arrival in power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1978 spelled the end of its most revolutionary foreign policy period, marked by support for various communist and Maoist insurgencies in the region. The ensuing period of reform and opening up signalled the start of a new stage in relations with Southeast Asia, and a return to the principle of non-interference. It was defined by globalisation and greater cooperation and economic integration.

Economics

Beijing has prioritised outreach to a region that currently comprises over 675 million inhabitants and constitutes the third economic force in the Indo-Pacific after China and India. As a whole, it accounts for around 15% of China’s total trade with the world and 14% of its investments1. Southeast Asia’s market has huge growth potential, it plays a prominent role in regional value chains and has rich agricultural, energy and mineral resources. For example, China has shown an interest in importing natural gas and oil from Myanmar and Malaysia; nickel from Indonesia and the Philippines; or foodstuffs – like rice and fruit –, reflecting a particular to attention food security, the importance of which has increased in recent years.

China is now the main partner of every country in Southeast Asia, assisted by the signing of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China in 2010 and the entry into force of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade deal in 2022. China was the region’s biggest trading partner in 2022, accounting for 21% of ASEAN exports and 24% of its imports. Vietnam (3.8%), Malaysia (2.4%) and Singapore (2.2%) are the main destinations of Chinese exports to the region in the sectors of machinery and electronic goods – with a percentage inside the three countries in excess of 40% –, which illustrates the role these economies play in regional value chains.

China’s huge Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) targets Southeast Asia as a primary area of operation in the development – and funding – of port infrastructures and overland corridors in order to smooth trade. Two of these corridors are expected to cross mainland Southeast Asia. The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor2, connecting China to India via the unstable Myanmar, and the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor, traversing the entire region from north to south, are prime examples of Chinese interests. Similarly, President Xi Jinping’s announcement of the Maritime Silk Road in Jakarta in 2013 illustrates the region’s importance in China’s rush to connect with Europe.

This desire for enhanced economic relations is apparent in the rapid rise in Chinese direct investment in the 10 countries, rocketing from $1.59bn in 2005 to over $30bn in 2018, although it decreased to $18bn in 2022. These investments prioritised manufacturing ($3.51bn), communication and information ($2.44bn) and real estate ($2.36bn) in 2021. Following a reduction in flows on account of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic downturn, China was the third biggest investor in the region in 2022 with 6.8% of the total, trailing well behind the United States (16%) and the European Union (10%) (ASEANStats, 2022).

By country, Indonesia is the biggest regional recipient, particularly in the logistics and mining sectors thanks to the country’s wealth of mineral resources and its geographical importance on maritime trade routes. Singapore is next, with significant investments in the real estate, technology and logistics sectors, owing to the country’s position on the Strait of Malacca (through which 80% of China’s oil imports transits). It is followed by Malaysia, thanks to major investments in financial services, natural resources and new technologies.

Diplomatic support

Beijing also needs political allies in its undisguised bid to steer the US-led global order towards a more multipolar world. To that end, it is not only key to win the Southeast Asian countries’ backing in the United Nations and for China’s new global governance initiatives; it is also important to secure their acquiescence on extremely sensitive domestic issues and vital affairs for Beijing, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong or Xinjiang. Regarding the latter issue, the silence on the plight of the Uyghurs from most Southeast Asian nations, including Indonesia – which has the world’s biggest Muslim population –, is a perfect example. They merely state that it is a Chinese domestic matter.

This search for allies is perhaps one of the most compelling features of the current age of systemic rivalry between the United States and China, in which Southeast Asia is a crucial area of competition between the two great powers.

Laos and Cambodia have been considered close to China for years, as two of the biggest recipients of Chinese development assistance in the region (Lowy Institute, 2023). But while Laos has accommodated the Asian giant to improve its domestic situation and regional standing compared to other actors in the neighbourhood– like Vietnam and Thailand – Cambodia has thrown in its lot with China (Pang, 2018). Of all the countries in the region, it is the one with most political affinity with Beijing, as their near identical voting record in the United Nations shows. In Myanmar too, following the army’s coup in February 2021 and the civil war afflicting the country since then, the military junta has swung towards China after receiving certain political support, and in spite of criticism of Beijing’s attitude from the rest of the ASEAN members.

At the same time, Washington has seen its influence over the ASEAN member countries wane, with the exception of Singapore and the Philippines thanks to the United States’ importance to both countries’ defence (Patton & Sato, 2023). In the Philippines, the Biden administration has enjoyed some recent significant success, however, such as the shift by the new government of Ferdinand Marcos Jr and the opening of new US military bases in 2023.

US-China Competition will be fiercest, then, in the countries where they both wield similar influence – like Vietnam and Thailand – and in those that have strong economic relations with Beijing, but close security and defence ties with Washington – like Indonesia, Malaysia or Brunei. Thailand in particular, as the natural leader on mainland Southeast Asia, is set to be a key battleground in the future struggle for hegemony in the region. A struggle in which China will continue to try to transform its huge economic power into political clout.

Troubled waters: the South China Sea dispute

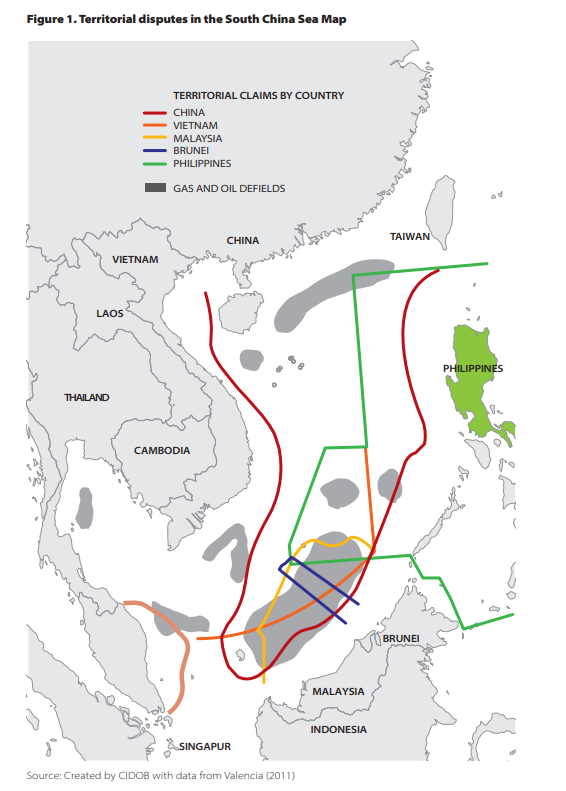

In parallel with China’s rise and the region’s economic integration, Beijing has stepped up its claims to sovereignty and jurisdiction over territory in the South China Sea (SCS). This has caused considerable friction with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei, which also claim jurisdiction over parts of the area. The dispute has been simmering since the 1970s, with military clashes between China and Vietnam in 1974 in the Paracel Islands, and 1988 in the Spratlys. But the number of incidents has increased since 2012, coinciding with a rise in China’s assertiveness and its inclusion of these territories as “core interests”.

Beijing is looking to strengthen a terrestrial and maritime security perimeter through the claim to historic rights in an area demarcated by the famous “nine-dash line” covering nearly 90% of the region’s waters, including the Spratly and Paracel Islands. This serves a triple purpose. First, to defend and protect China’s mainland coastal provinces, home to the country’s economic powerhouse and a large part of the population. Second, to safeguard the shipping routes of a region through which around 65% of China’s trade transits and, at the same time, pierce the barrier of US islands blocking China’s development as a sea power. Third, Beijing also aspires to force through the reorientation of a huge maritime space that is vital to its political and economic stability, thereby demonstrating its leverage in the vicinity as a major power in the Indo-Pacific.

The International Court of The Hague ruling of 2016 on ownership of the Mischief Reef in favour of the Philippines and its rejection of China’s claims of historic rights in the SCS for lack of legal foundation marked a new milestone in the dispute. The authorities in Beijing rejected the arbitration, contradicting the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that China ratified in 1996. China has embarked on a growing militarisation of the islands over which it exercises de facto authority to reinforce its control of the maritime area for defensive purposes, particularly through the construction of dual-use (civilian and military) infrastructures and coercive action on the part of Chinese coast guard.

These moves by China have been accompanied by a regional trend for increased defence spending, particularly visible in the case of the PRC, with the modernisation of the People’s Liberation Army serving hegemonic designs in the Asian region, thereby increasing tension and the risk of accidents. This conduct is precisely what has raised most hackles among China’s neighbours, particularly in the Philippines – which has a Mutual Defence Treaty with the United States –, Vietnam and, to a lesser extent, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. It brings back painful memories of violence experienced in a colonial past under Europe and Japan, or the imprint of the Cold War, such as the Vietnam conflict.

China as a disruptor of the ASEAN consensus

China and ASEAN have gradually strengthened relations since the 1990s, facilitating a process of mutual institutional convergence. If initial contact with ASEAN dates back to 1991, by 1996 China had already acquired the status of ASEAN’s full Dialogue Partner. Since then, China has gone on to form part of all the cooperation mechanisms established by the organisation, like ASEAN Plus Three – an economic cooperation platform comprising ASEAN and South Korea, Japan and China – or the East Asia Summit – a forum for regional cooperation and strategic dialogue formed by the 10 ASEAN member states, Australia, China, Japan, India, New Zealand, South Korea, the United States and Russia. Since Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, however, the importance and intensity of Southeast Asian interaction has increased, given the region’s primacy in a “neighbourhood diplomacy“ aimed at ensuring a favourable local environment for its security and development.

In parallel, China is also a divisive factor in ASEAN’s unity of action on such vital matters as the SCS wrangle. Cambodia plays a leading role in this, impeding an ASEAN consensus on the dispute. Along with the increase in internal challenges, like the Myanmar issue and the organisation’s non-interference principle, and external developments, such as the creation of the AUKUS (the military alliance between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States) or the war in Ukraine, there is concern about growing disunity among ASEAN members. According to the State of Southeast Asia 2023 Survey, 61% of respondents thought ASEAN was increasingly fragmented and 73% feared the transformation of the institution into an arena of geopolitical competition between powers where its members act as proxies of the great powers’ interests.

Southeast Asia rises up

Southeast Asia is crucial to China’s designs as a regional and global power given the importance of its neighbourhood as an area of natural influence. The view of China held in the region has changed enormously in recent decades. While some governments initially perceived it as a threat because of its support of communist insurgencies, China has now become an indispensable trading partner and crucial to maintaining economic development, as well as a major regional actor. But that preeminent role as a trading partner does not mask deep suspicion triggered by its aggressive policy in the SCS, its political rise in the region, emerging hegemonic tendencies and the economic reliance on China the countries of the neighbourhood have acquired.

In terms of soft power, China has made a major incursion into cultural affairs through the Confucius Institutes – there are now over 30 throughout the region – and a huge scholarship programme to study in the PRC. Yet for all the activity aimed at improving the country’s image abroad, China is neither as popular nor as loved as the giant would like. Despite enormous and enduring economic and political clout, it is perceived as a revisionist power which aims to transform the region into its area of influence.

And here lies one of the chief sources of prospective instability: the difficult balance between China’s goals of a higher profile as a regional leader, its expansionary policy in the SCS and the response from the Southeast Asian nations. It is a complex situation, since one of the most important legacies of the colonial era in the region was the need to fight for freedom and independence. That is why, though the tension is hidden, if Beijing continues to display hegemonic behaviour, we cannot rule out a deterioration in relations between China and the Southeast Asian countries as a whole.

References

ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Statistical Yearbook 2022. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, 2022. https://www.aseanstats.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ASYB_2022_423.pdf

ASEAN Stats. “Flows of Inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into ASEAN by Source Country (in million US$)”. ASEAN Stats Database. https://data.aseanstats.org/fdi-by-hosts-and-sources

Pang, Edgar. “Same-Same but Different: Laos and Cambodia’s Political Embrace of China”. ISEAS Yusof-Ishak Institute Perspectives, 66 (2017). https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ISEAS_Perspective_2017_66.pdf

Patton, Susannah & Sato, Jack. Asia Power Snapshot: China and the United States in Southeast Asia. Sidney: Lowy Institute Report, 2023. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/API%20Snapshot%20PDF%20v3.pdf

Seah, Sharon et al. The State of Southeast Asia 2023 Survey Report. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Institute, 2023. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/The-State-of-SEA-2023-Final-Digital-V4-09-Feb-2023.pdf

Lowy Institute. “Southeast Asia Map Database”. Lowy Institute (2023). https://seamap.lowyinstitute.org/

Notes:

1- See Appendix, Table 5.

2- The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor is currently on pause given India’s reticence to join the Belt and Road Initiative and the domestic instability of Myanmar, especially after the Military Junta coup d’état in 2021.