China in the South Pacific: geopolitical competition and local agency

The presence of the People’s Republic of China in the South Pacific is shaped by its contest for international recognition with Taiwan and its (re)emergence as an economic power. Since 2022, Beijing’s geopolitical calculations in relation to the Western powers have altered China’s footprint in the region, adding a new security dimension. Yet this presence cannot be understood without considering the agency of the 14 island states and their desire to determine the Pacific’s future.

In 1994, Fijian anthropologist Epeli Hau’ofa defined the South Pacific as “Our Sea of Islands”. This phrasing sought to break with the notion of the region as a group of small, remote and vulnerable island states in order to place the ocean at the heart of their identity and independence. The discursive shift would subsequently serve as a platform for the Pacific nations to reframe themselves as “large ocean states”, with control over vast maritime areas. The region, comprising 14 sovereign island states plus seven territories under European or United States control1, covers 15% of Earth’s surface area and is rich in natural resources like wood, minerals, fisheries and seafloor deposits.

However, despite these local attempts at self-definition, the narrative of realpolitik appears to prevail in the South Pacific. Its history is marked by the shadow of colonialism, its strategic importance during the Pacific War and the perception of the region as an exotic—and unstable—backyard of Australia and the United States. The consolidation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the zone over the last two decades and its presumed impact on the regional order has resurrected old dynamics of geopolitical rivalry. The signing of a security agreement between the Solomon Islands and China in April 2022 and the (rejected) proposal of an interregional agreement with 10 island nations has sparked a fresh wave of interest. The islands, however, are adamant they will determine the future of the region and its bilateral and multilateral relations on their own terms.

The Taiwan factor

Relations between the PRC and the Pacific nations date back to the 1970s, when Beijing began to provide development assistance to the new postcolonial states as it jostled for international recognition with Taiwan. At the time, both capitals laid claim to the status of legitimate representative of the Chinese government in the international system. And for decades, China and Taiwan employed what was known as “chequebook diplomacy”. In other words, they offered foreign aid and other incentives, including bribes and diplomatic support in the United Nations (UN), on one condition: the establishment of official diplomatic relations. The island states, in need of an economic boost following independence, created a “market for diplomatic recognition” that rooted both actors to the region (Atkinson, 2010).

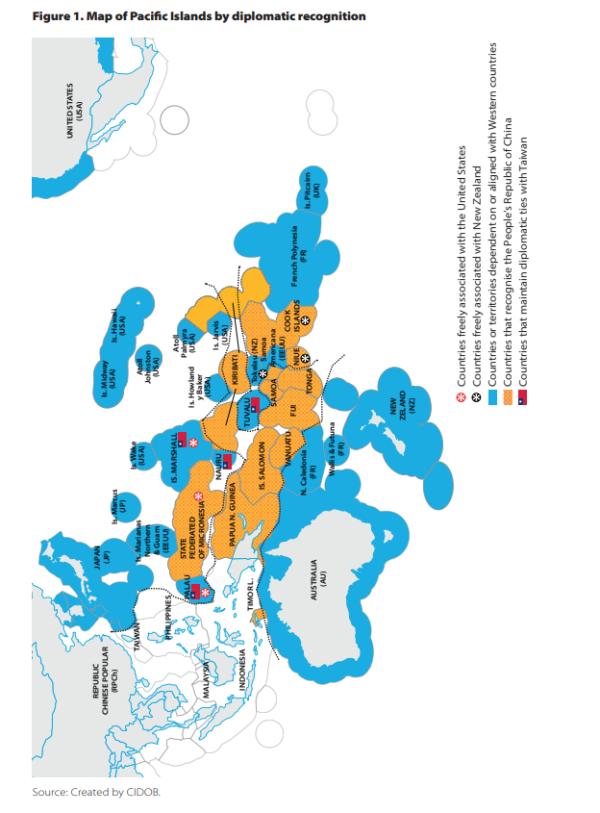

Competition was fierce in the 2000s, with economic assistance, the cultivation of bilateral and multilateral relations via high level visits and the creation of regional cooperation frameworks. A more conciliatory tone towards Beijing from Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou, of the Kuomintang (KMT), eased this rivalry between 2008 and 2015. But the arrival in power of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 2016 under Tsai Ing-wen, and her staunch defence of Taiwan’s sovereignty, reignited the competition between them. Since then, Taiwan has lost eight diplomatic allies around the world, two of them in the Pacific. The Solomon Islands and Kiribati broke off relations with Taipei less than a week apart in 2019. Currently, 10 of the South Pacific’s 14 island states recognise the PRC diplomatically and just four recognise Taiwan—Nauru, Tuvalu, Palau and the Marshall Islands.

As well as the initial catalyst of Beijing’s engagement in the South Pacific, recruiting states from this zone in support of the “One China” principle and reducing Taipei’s influence in the region remains a key issue for the PRC to this day. If we bear in mind that four of the 13 diplomatic allies that Taiwan has left in the world are in the region, the Pacific is of major importance to Chinese interests.

Yet the Pacific states have not been mere spectators of this rivalry; they have stoked it and leveraged it at will according to their interests, weighing up the benefits and challenges of recognising one or the other. Several countries have switched sides in this competition multiple times, be it because of changes in government (Papua New Guinea in 1999; Tuvalu in 2004; or Vanuatu in 2006), a leader’s personal financial gain (Kiribati in 2003), promises of development assistance (Solomon Islands and Kiribati in 2019) or more specific but crucial reasons, such as the reestablishment of the country’s only airline (Nauru in 2004). The most recent example was in 2023, when, just before leaving office, President of the Federated States of Micronesia David Panuelo declared he was ready to recognise Taiwan to the detriment of the PRC in return for initial aid of $50m and a further $15m a year for a period of three years (Needham, 2023).

China in the South Pacific: between global trends and geopolitical interest

The first indication of a shift in relations between the South Pacific and China came in 2006. The creation of the Economic Development and Cooperation Forum between Beijing and the—then eight—Pacific Islands nations that recognised the PRC diplomatically provided for preferential loans, the removal of trade tariffs and the cancellation or renegotiation of debt. Since then, China has consolidated its presence in the region with diplomatic visits at the highest level, including President Xi Jinping’s trips to Fiji (2014)—the first to the region by a Chinese leader—and Papua New Guinea (PNG) (2018), plus multiple aid packages (including a $4bn pledge in 2018 that failed to materialise). There are several reasons for this surge. In addition to the rivalry with Taiwan, identity issues (the Chinese elite’s commitment to south-south cooperation); economic and trade motives (the interests of state-owned and private extractive companies and access to new markets); political grounds (the islands’ support in the UN); and geopolitical reasons (gaining political and economic clout in the region and breaking the chain of islands in the US orbit) account for this strengthening of ties.

While economic and diplomatic relations between Beijing and the South Pacific have increased substantially over the last two decades, it is in line with the global trend accompanying China’s transformation into a major trading power. According to the Office of Pacific Trade and Investment in Beijing (2020), total trade between China and the independent nations of the Pacific came to over $7.7bn in 2019. PNG and the Marshall Islands are China’s main trading partners in the region (nearly 40% of the total in 2022), well ahead of other states such as the Solomon Islands or Fiji, which account for less than 10% of China’s regional transactions. PNG is of greater importance because of its position as an exporter of liquified natural gas, nickel, cobalt and fish, and it attracts the biggest Chinese investments, like the $1.4bn Ramu nickel mine. American Enterprise Institute (AEI) figures (2022) suggest PNG has captured 90% of Chinese investment in the South Pacific over the last 17 years. Yet in aggregate terms, the region barely accounts for 0.2% of China’s global trade, which shows that economic interests do not drive its affairs in the zone.

What has attracted most attention in the region is the rise in Chinese development assistance without the “conditionality” of political reforms other than diplomatic recognition. According to Australian think-tank Lowy Institute’s data base (2022), China committed over $3.7 billion to the region between 2008 and 2020. Papua New Guinea ($964m), Fiji ($378m), Samoa ($362m) and Tonga ($300m) were the main recipients. Beijing provides 9% of the total development aid allocated to the region, making it second only to Australia (36%). But for China the assistance devoted to Oceania amounts to less than 4% of its total foreign aid, given the small size of these economies. After peaking at $333m in 2016, its volume is declining and its size in the future is in question (Smith, 2021).

Contrary to the widely held view of China as a unitary actor implementing a master plan for the region, the truth of the matter is that many of the development assistance projects are not managed from Beijing. Instead, they are run from Guangdong province, the origin of most of the Chinese diaspora in the South Pacific, and from the head offices of some of the companies with greatest presence there, like the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation or the China Harbour Company. In practice, the most important projects in the South Pacific are in fact promoted by local companies (or politicians) and Chinese contractors that seek funding from institutional banks specialising in investment abroad, like Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank). The result is a fragmented, bottom-up approach to aid adoption guided by commercial interests that has led to some successful projects, but also some flops and criticism of its ineffectiveness (Smith, 2018). The South Pacific’s incorporation into the southern route of the Maritime Silk Road in 2016, however, is seen as a bid for coherence from Beijing in its action and that of the various Chinese stakeholders in the region.

In addition, most of the development assistance has come in the shape of loans, fuelling concerns about a possible “debt trap” that strikes such a chord in other regions of the Global South. The evidence, however, suggests otherwise, at least in the South Pacific. In the case of Tonga, we have seen how China has agreed to a payment deferral on two occasions to avert debt default (2013 and 2018). And this is not the only example of a country where Beijing has forgiven debt or agreed to alternative repayment methods. According to the researcher Alexander Dayant (2020), moreover, while these countries have racked up debt, it has been due to reconstruction after natural disasters, not the China factor.

Zhou Fangyin (2021), expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), says that until 2022 there was no clear evidence that the Chinese elites had prioritised the region strategically, politically or economically. But this could be changing following the signing of the security agreement between the Solomon Islands and China in 2022. The deal allows the Solomon Islands government to seek the support of Chinese police and military personnel. And, with Solomon Islands consent, it offers China the possibility of protecting its interests and citizens in the country, as well as providing for Chinese ship “visits”. It is a major plus to the relations Beijing has traditionally forged in the zone. Security also featured in the proposed multilateral pact a “Common Development Vision” that China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, offered the Pacific Island countries in May 2022 and which they rejected on the spot. These moves have raised the alarm in Australia and the United States. They are making a bid to return to the South Pacific with new policies, which include blocking strategic telecommunications deals between China and some of these countries, the signing of new security agreements (like the new agreement between the US and PNG that grants an unrestricted increase in US military presence in the country in return for infrastructure) or the reopening of embassies in the island states. This has been met with concern in Beijing, which appointed a Special Envoy for Pacific Island Affairs, Qian Bo, in 2023, redoubling efforts to ensure coordination among all the actors involved and declaring a previously veiled geopolitical interest.

The “Blue Pacific” and local agency

While geopolitics is a visible dynamic in the region, the competition between major powers tends to mask other realities—and agendas—that, far from assuming the Pacific Island states are mere pawns in a geopolitical game, place the emphasis on an indisputable fact: the Pacific nations’ own agency.

China’s presence in the Pacific cannot be explained solely through Beijing’s agenda; it is also shaped by the interests and capacities of the island governments to engage the multiple actors present in the region to their benefit. Zealously protective of their sovereignty and independence, they exert their capacity to switch allegiances depending on their economic interests and maximise their latitude in the face of former regional powers that still wield considerable influence. Until recently, China was a vocal exponent of the principle of non-interference and of funding infrastructures that no other donor would sponsor. It has been the local elites themselves, then, who had the greatest interest in feeding the narrative of China’s huge influence to Western audiences (Hameiri, 2015), looking to see them re-engage in the region. In contrast, this has fuelled tension and local negative perceptions in relation to the Chinese diaspora, accompanied by violence in some cases.

Since 2017, the Pacific Island leaders have asserted their agency and identity with the construction of the “Blue Pacific” framework that unites and mobilises the countries on matters that are important to them, such as the existential threat posed by climate change. This new narrative champions regionalism, collective decision-making and the commitment to operating as a united and interconnected “Blue Continent” in the face of changes in the regional order (Kabutaulaka, 2021).

It is these same states that have been quick to voluntarily reject Beijing, as well as other actors in the region, when their agency, interests or established deliberation mechanisms have been snubbed. The rejection of Wang Yi’s proposal of greater development and security cooperation or the resistance on the part of Nauru, Tuvalu, Palau and the Marshall Islands to cease recognising Taiwan are clear examples of this capacity to stand firm. As was the signing of the security agreement between the Solomon Islands and China despite enormous pressure from the United States, Japan and Australia. As Henry Puna, the secretary general of the region’s main multilateral platform the Pacific Islands Forum, recalled, any actor who fails to take account of its “collective ability to think, live, engage and deliver as one Blue Pacific region” will find it hard to advance their interests—and that includes China.

References

Atkinson, David. “China–Taiwan diplomatic competition and the Pacific Islands”, Pacific Review, vol. 20, nº nº4 (2010), p. 407–427.

Dayant, Alexandre. “¿Un océano de deudas? Gestionar la Diplomacia de la Deuda china en el Pacífico”. Anuario Internacional CIDOB 2020 (2020), p. 235.

Dziedzic, Stephen. “China wanted a swift diplomatic victory in the Pacific. But the region’s leaders won’t be rushed”. Islands Time (June 3, 2022).

Hameiri, Shahar. “China’s ‘Charm Offensive’ in the Pacific and Australia’s Regional Order”. Pacific Review, vol. 28, nº5 (2015), p. 631–654.

Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius. “Mapping the Blue Pacific in a Changing Regional Order”, in: Smith, Graeme and Wesley-Smith, Terence. The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands. Canberra: ANU Press, 2021.

Lowy Institute. “Pacific Aid Map Database”. Lowy Institute (2022). https://pacificaidmap.lowyinstitute.org/

Needham, Kirsty. “Pacific's Micronesia in talks to switch ties from Beijing to Taiwan-letter “, Reuters (March 10, 2023).

Office of Pacific Trade and Investment in Beijing. Trade Statistical Handbook Between China and the Pacific Islands 2020. Beijing: Pacific Trade and Investment, 2022.

Smith, Graeme. “The Belt and Road to nowhere: China’s incoherent aid in Papua New Guinea”. The Interpreter (February 23, 2018).

Smith, Graeme. “Ain’t No Sunshine when Xi’s Gone: What’s behind China’s Declining Aid to the Pacific?” Australia National University: In Brief, nº21 (2021).

Zhou Fangyin. “A Reevaluation of China’s Engagement in the Pacific Islands”, in: Smith, Graeme y Wesley-Smith, Terence. The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands. Canberra: ANU Press, 2021.

Notes:

1- The 14 sovereign island states are the following: Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Salomon Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua Nova Guinea, Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. The seven territories under Western control are the Mariana Islands (US), New Caledonia (FR), French Polynesia (FR), American Samoa (US), Tokelau (NZ) and Wallis and Futuna (FR).