The world in 2022: ten issues that will shape the international agenda

Text finalised on December 14th 2021. This document is the result of the collective reflection of the CIDOB research team in collaboration with EsadeGeo. Coordinated and edited by Eduard Soler i Lecha, it has benefited from contributions by members from both organisations (Hannah Abdullah, Inés Arco, Anna Ayuso, Jordi Bacaria, Ana Ballesteros, Pol Bargués, Moussa Bourekba, Anna Busquets, Carmen Claudín, Carme Colomina, Emmanuel Comte, Carlota Cumella, Anna Estrada, Francesc Fàbregues, Oriol Farrés, Agustí Fernández de Losada, Blanca Garcés, Eva Garcia, Andrea G. Rodríguez, Juan Garrigues, Francis Ghilès, Seán Golden, Berta Güell, Juan Ramón Jiménez-García, Francesca Leso, Josep Mª Lloveras, Rafael Martínez, Esther Masclans, Óscar Mateos, Sergio Maydeu, Elisa Menéndez, Pol Morillas, Yolanda Onghena, Umut Özkirimli, Francesco Pasetti, Cristina Sala, Héctor Sánchez, Ángel Saz, Reinhard Schweitzer, Antoni Segura, Cristina Serrano, Eloi Serrano, Marie Vandendriessche, Pere Vilanova and Eckart Woertz) as well as several individual partners of CIDOB.

In 2022 the world is more certain about the challenges it faces and more aware of its vulnerability and interdependence. The future is always uncertain, but today’s doubts are less about what and more about how, who and until when. The problem is not one of diagnosis. Data and conclusions abound about the importance of the present moment and the major transitions underway in the digital, green and labour fields. But the failure to carry them out collectively and inclusively leaves us in a fractured landscape. Key to the debate are the questions around where the point of no return lies, what kind of leadership is best equipped or has most legitimacy to pilot these transformations and how the process should be handled to ensure the social costs are as low as possible.

What will be special about 2022? The advancing vaccination programmes should ensure that at some point this year – perhaps later than initially hoped – the damage can be counted and we can begin to look forward. One of the year’s major themes will therefore be the long-awaited recovery and everything that might frustrate it (prices, geopolitical tensions, bad news in the health sphere). In this process of post-pandemic restart, it will be clear that the world is not only advancing at different speeds, but that some groups will end up worse off than before, for example, in terms of mobility and humanitarian crises. One of the most frequently asked questions this year will be whether we have learned from the pandemic to face global challenges with greater anticipation, ambition and solidarity.

Economic recovery

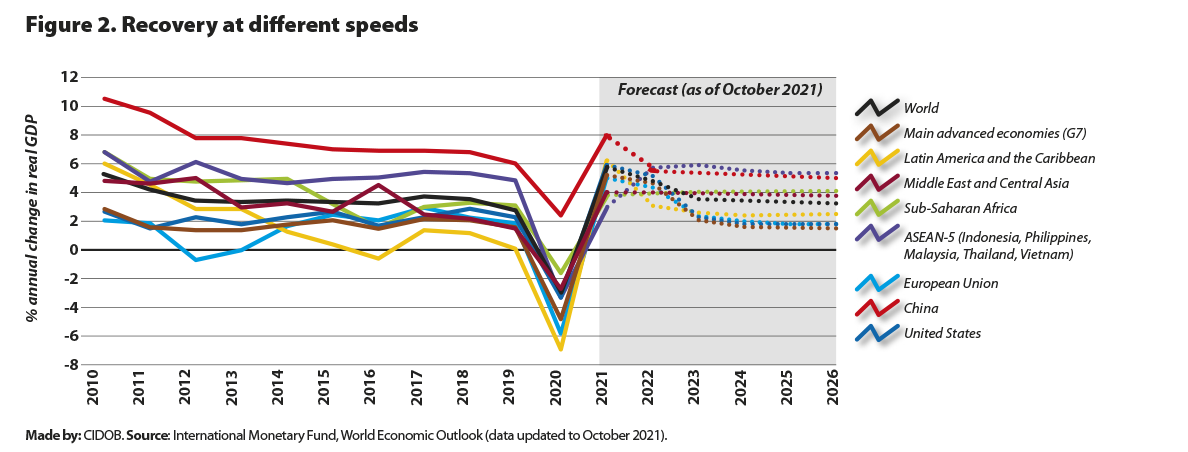

The COVID-19 outbreak brought the economy to an unprecedented halt, with GDP dropping 4% globally in 2020 and over 10% in places such as Spain. According to the International Labour Organization, at the height of the health crisis 33 million people joined the ranks of the unemployed and 81 million left the labour market. Household consumption fell by 5% on average worldwide, with some major economies such as Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Argentina, and Mexico seeing declines of more than 10%. In economies that depend on international mobility, the fall was even steeper: Singapore (-14%), Macau (-16%) and Mauritius (-18%).

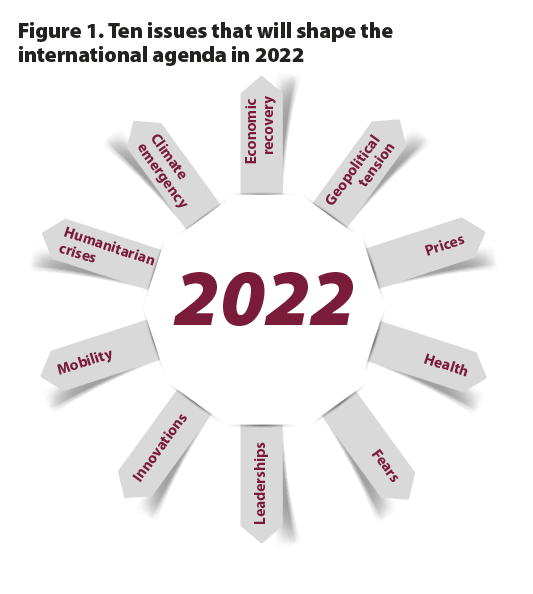

Once the initial shock had passed, the production of a vaccine in record time and ambitious stimulus plans opened up a path towards recovery (see figure 2). In our foresight exercise for 2021 we warned that this would be a K-shaped recovery. In other words, certain countries, territories, economic sectors, and social groups would enter a phase of boom and optimism, with the pandemic having passed, while others would remain mired in a social, economic and emotional depression.

Data from 2021 show that inequalities between and within countries have increased and that this bifurcation could continue to widen. Oxfam has revealed that the wealth of global billionaires has increased by $3.9 trillion since the start of the pandemic, about the same amount lost by the working classes. The recovery is also gendered. In October 2021 the ILO noted that while male employment levels were recovering, the same was not true for working women.

The economic and social drama was eased by the measures implemented to support particularly vulnerable groups, expansionary fiscal and monetary policy and stimulus plans of varying magnitudes. With the state playing a larger role in both managing the pandemic and in the recovery strategies, the Washington Consensus of budgetary discipline and limited state intervention was once again called into question. In 2022 these measures will be evaluated and the duration of their implementation will be discussed, along with their financing. Debate will turn to developed economies’ high levels of indebtedness, although large-scale cuts and significant changes to monetary policy to cope with price rises will continue to be deferred. More urgent will be the financial stress facing middle-income economies, with currencies like the Turkish lira depreciating, and possible sovereign debt crises.

The starting points vary a great deal. As 2022 begins, the United States, China and India may be colour-coded green, with pre-pandemic GDP levels already reached. Others – including almost all eurozone countries –hope to reach this goal at some point in the year. But with low levels of growth forecasted, a significant minority are red. Predictions for the Global South are particularly worrisome, where population growth continues to demand high economic growth rates. The IMF forecasts very weak growth of 1.5% for Brazil, Latin America’s largest economy, and rates of below 3% for the two largest economies in Sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria and South Africa (see figure 3).

In 2022, the international economic debate will try to clear up five unknowns: the solidity and sustainability of the recovery in developed economies; the level of vulnerability of middle-income economies; the degree of disparity in the behaviour of the so-called emerging economies; price rises and supply bottlenecks and blockages as matters of global concern; and, finally, the likelihood and potential impact of the Chinese bubble bursting, especially since the warning sign of the crisis of the real estate holding company Evergrande.

Even if these risks are avoided, the economic recovery agenda will face opposition; if the mentioned dangers materialise, that opposition will be all the greater. In 2021 there have already been signs that protests put on hold in 2020 due to the mobility restrictions imposed to control the spread of the virus have resumed. The pandemic is worsening pre-existing discontent and in some places the situation has deteriorated rapidly. Lebanon, for example, faces elections in 2022 in the midst of economic and social upheaval. Another factor is the dissatisfaction expressed by what we might call the “new poor”. Latin America merits particular attention both in terms of pre-existing discontent and its shrinking middle class. The World Bank warns that 82% of the 72 million new poor live in middle-income countries, are urban-based, educated and depend more on the informal sector than the existing poor.

Nevertheless, early awareness of the impact of these threats to the recovery, the magnitude of the costs of a second shock in such a short space of time and the recognition of the risk of social combustion could act as deterrents or as an incentive to avoid them. Again, the diagnosis is clear; the response is what remains unknown.

Geopolitical tension

Great power tensions will set the global geopolitical pace and condition the prospects of recovery. The US–China relationship has become the international system’s structuring rivalry. Added to this is the risk of escalation in Ukraine, with the deployment at the end of 2021 of over 100,000 Russian troops at the border, and the US stating that any aggression would be met with a response. Along with these two great rivalries, tensions are resurfacing between states such as Algeria and Morocco, China and India and, to a lesser degree, Egypt and Ethiopia.

When seeking to take the geopolitical temperature, many eyes also turn to Taiwan. As 2021 ended, concerns were rising about the global effects of the rising tensions over Taiwan, especially with Chinese incursions into the Taiwanese air defence zone and Xi Jinping warning the US about “playing with fire”. This has reignited the intense debate over the sustainability of the current status quo and the inevitability of a confrontation between the two superpowers. Taiwan is not the only hot spot. In 2022 we should pay attention to how the rivalry reverberates in other arenas of competition, such as the South China Sea, the Korean peninsula, the opening up of Arctic routes and trade wars.

Only a decade ago has passed since Barack Obama announced the "pivot to Asia". In 2021 we saw that not only would the US maintain its security commitment, it would strengthen it through the security partnership with Australia and the United Kingdom as part of the AUKUS alliance. In the second decade of the 21st century, the definition of the space where this battle is being played out has changed, with the idea of the “Indo-Pacific” fully normalised and expanded. This is leading to new collaborations not only between Washington and Canberra, but also with Delhi and Tokyo, breathing new life into the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD).

China, for its part, is promising a partnership of equals to African nations as part of its growing ambitions in this continent. Meanwhile it is expanding the horizons of its global influence in Latin America, where it is already the main trading partner. Vaccine diplomacy joined infrastructure investments and debt purchasing as part of the foreign policy toolbox in 2021, and China has pledged to donate 2 billion vaccines to the world for 2022. But the United States and its allied countries seem particularly concerned about the advances in quantum computing, as shown by Washington placing a dozen Chinese companies on an export blacklist. Meanwhile, China’s increasing military assertiveness is reflected in a defence spending rise of 6.8% compared to 2020 and in the new reports of hypersonic weapons testing.

The transatlantic connection will also be under the spotlight, especially during the NATO summit in Madrid on June 29th and 30th 2022. This meeting will help us gauge the levels of convergence and trust between the United States and its European allies and understand the alliance’s stance on China. Will it be explicitly mentioned in the new strategic concept? Madrid will also reveal the state of relations between Turkey and its Western allies. While the grievances have been piling up on both sides, thus far a divorce has been avoided, even after the Erdoğan government’s controversial acquisition of the Russian S-400 missile defence system. The focus of the summit will also be conditioned by Vladimir Putin's actions on the alliance’s eastern flank. Another of NATO's priorities will be cybersecurity. The Alliance will try to catch up in the innovation race, especially when it comes to emerging and disruptive technologies, and advancing on the implementation of the Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA). Changes are also expected in the leadership of the organisation. Jens Stoltenberg’s term ends in September and efforts are underway to appoint a female Secretary-General for the first time.

Strategic autonomy has become the buzzword in the security field in the European Union. As an idea, it connects with the vision of a more geopolitical Europe proclaimed by the leaders of the European Union institutions and certain member states (e.g. Emmanuel Macron). From 2022 it should be translated into concrete actions. The pandemic and the US’s unilateral decisions in the Indo-Pacific and Afghanistan suggest that the EU cannot keep dragging its feet. In the first half of 2022, with France assuming the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU, the Strategic Compass will be adopted, a document that will identify challenges and threats, articulate capabilities and attempt to project Europe’s influence as a regional and global actor with greater force and coherence. The other milestone will be the defence summit, also under the French presidency. Indeed, Charles Michel has called 2022 "the year of European defense". The degree of consensus among EU members will to a large extent depend on the solidity and effectiveness of the positions taken on defusing Russian threats of aggression. Finally, the adoption of the so-called NIS2 Directive, which aims to protect networks and communication systems against cyberattacks, should also speed up this year.

To what extent will the EU seek to project itself towards the Indo-Pacific? Or will it continue to focus on spaces closer to home? If it decides to try and keep pace with the two superpowers, it will look to the Indo-Pacific and we will see cooperation with the United States and competition with China play larger roles on the security agenda. However, the balance can quickly tip the other way. The EU will be forced to concentrate on matters in its neighbourhood if tensions rise in Ukraine or Belarus or between Morocco and Algeria. The common thread in the destabilisation in both the EU’s neighbourhoods (eastern and southern) is an impact on the energy and migration agenda, with gas pipelines and refugees being used as means of exerting pressure and even blackmail.

Although fewer in number, opportunities also exist for détente at global level, with Iran being the most important. The situation is more complicated than in 2015, but multilateral negotiations on Iran's nuclear programme continue. The remaining area of doubt is whether Israel will act unilaterally if it considers that the negotiators concede too much. One novelty at regional level are the gestures of appeasement between Saudis and Iranians seen, for example, at the United Nations General Assembly. Representatives of the Middle East’s key regional powers even managed to meet in Baghdad in August 2021 and Saudi Arabia is considering reopening the Iranian consulate in Jeddah. In a year of high geopolitical voltage and with upward pressure on energy prices, the consolidation or otherwise of this phase of détente around the Strait of Hormuz will be decisive.

Prices

Restarting the global productive and logistical machinery is proving more arduous than anticipated. Fears that the inflationary spiral and episodes of scarcity will compromise the economic recovery or call into question globalisation as we have known it have catapulted this issue to the very top of the economic, political and social agendas.

The price rises have more than one cause. The effects of higher levels of consumption and liquidity resulting from stimulus plans and surplus savings were taken for granted. Less expected were the accumulating disruptions to supply chains, lack of raw materials such as wood and its derivatives like paper, gridlock at ports and production and distribution bottlenecks. Added to the restrictions imposed by large economies such as China to control the pandemic are labour shortages in essential positions, as the recent problems finding truck drivers in the United Kingdom and United States show. The decision by the oil-producing countries – particularly Saudi Arabia – to refuse to inject more oil into the market has contributed to increasing upward pressure.

Energy price rises will be among those with most geopolitical effect. The World Bank forecasts that the upward trend will continue throughout the winter of 2022, spurred by higher consumption during the northern hemisphere’s winter whose causes can be traced back to lower investment in the previous cycle, concentration of demand in Asia and insufficient storage capacity. It is hoped that prices will fall from spring onwards. But the level of uncertainty is very high and is to a large extent determined by the evolution of the pandemic. Scenarios of rapid recovery and prices temporarily above $100 a barrel must therefore be contemplated. The huge price swings of the past two years may presage future price rise episodes that are more extreme and frequent.

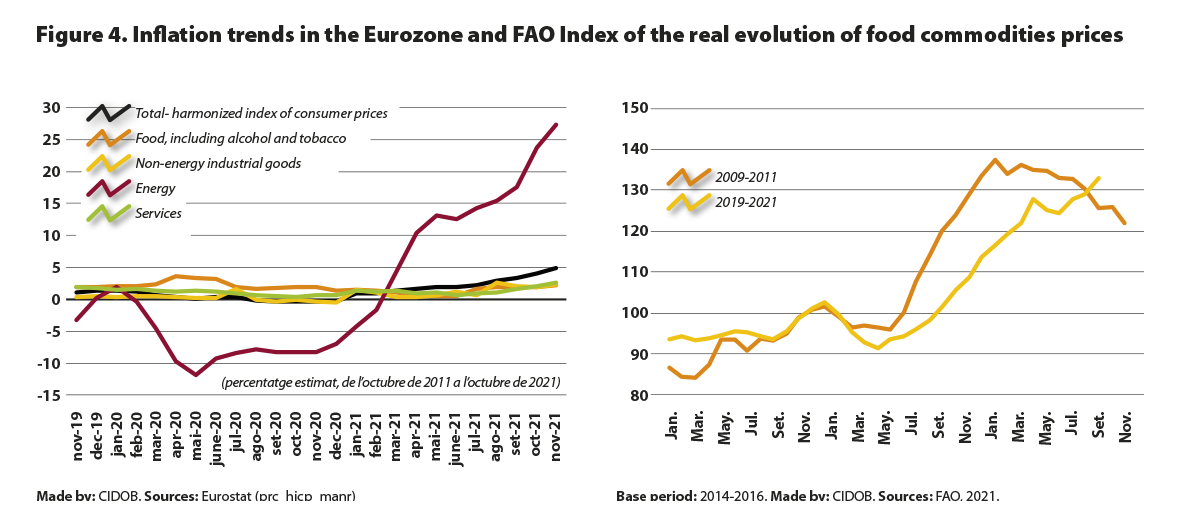

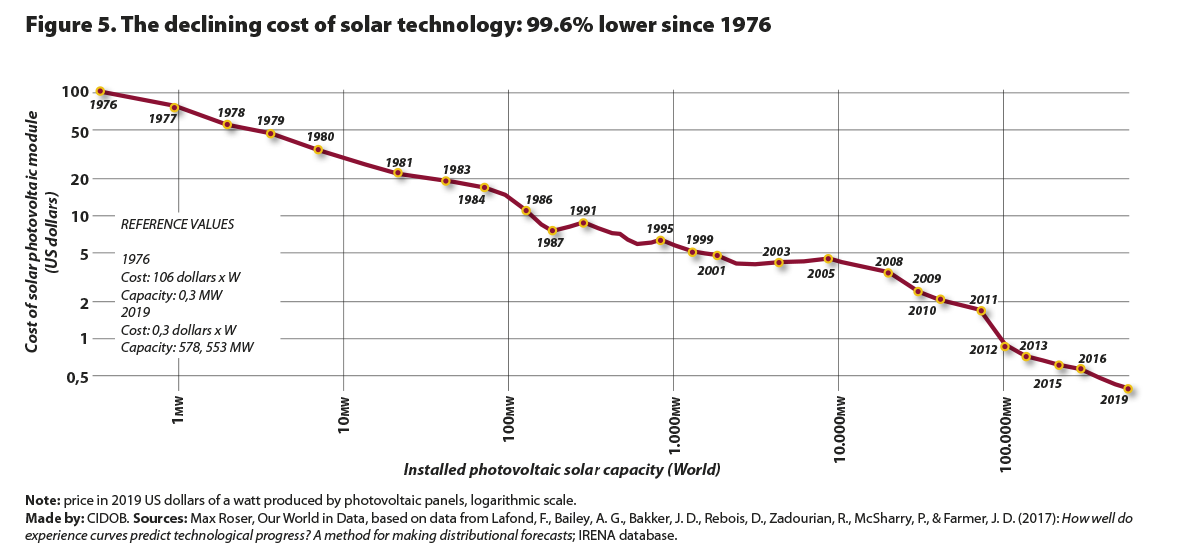

For high-income countries, this will fundamentally translate into higher inflation, as higher energy prices impact all other products, even if only due to transport costs. At the end of 2021 inflation was at 4.9%, according to Eurostat, the highest level for 20 years (see figure 4). And higher inflation means more public spending. This period of high prices may have paradoxical effects, on the one hand accelerating the implementation of renewable energies, whose low costs continue to break records (see figure 5), while at the same time increasing the unpopularity of measures to tax the use of fossil fuels and the lifting of subsidies in line with the commitments made at the G7 and COP26.

A second category contains the countries that import energy and have fewer resources to cope with increased costs. This is where supply problems can occur. Lebanon is one of the most extreme cases, with shortages of essential products like milk, petrol, and medicines, but it is not alone. The energy dependence of Pakistan, Bangladesh and several Latin American countries further compromises the economic recovery. Another case generating perplexity is China’s power outage.

In this second group, special mention should be made of the countries suffering the double shock of energy and food price rises. There is a link between the two, since higher natural gas prices substantially drive up the price of producing fertilisers. The Food Price Index rose relentlessly in 2021, forcing us to consider whether the episodes of political and social destabilisation that occurred in 2010 will be repeated and the possible impact on humanitarian crises.

The third bloc of countries is made up of producers like Russia, Saudi Arabia and Algeria. Some may take advantage of the increased income to accelerate ongoing processes of economic diversification. But more short-sighted attitudes are more likely to prevail. Rentier regimes will postpone their energy transition plans, as a welcome and unexpected injection of resources allows them to buy social peace, co-opt critical voices, strengthen the state’s repressive capacities and rebalance power relations with their international partners.

And yet for the companies and societies most involved in the planet’s sustainability a number of opportunities will arise. We should get an idea of the extent to which the combination of environmental awareness and supply problems consolidate different consumption patterns, a commitment to resize global value chains and provide a boost to the circular economy.

Health

The spread of COVID-19 shot health to the top of the international agenda: there was the push for international cooperation on healthcare, the geopolitical use of the vaccine, and good or bad health management became a key ingredient of soft power. Success or failure on immunisation, and the emergence or otherwise of effective COVID-19 treatments are decisive factors with a strong bearing on the political, economic and social agenda at all levels.

One of the main risks identified by epidemiologists is the emergence of new variants of the virus that could be contagious, lethal, or resistant to current vaccines. Indeed, 2021 ended with new alarm over the appearance of the Omicron variant. The longer large pockets of the world’s population remain unvaccinated, the higher the chances of these situations are recurring.

However in 2022 access to vaccines among the countries left behind in the vaccination drive should improve, in part because of the steady increase in production capacities – the EU estimates that it will produce 3.5 billion doses in 2022 and Modi announced that India will produce another 5 billion. Africa is the main challenge since, with the exception of places like Morocco, Cape Verde and Tunisia, immunisation levels remain below 10% as of December 2021. Countries in conflict merit special mention, because the issue is not only access to vaccines, but distribution problems and the critical state of their healthcare systems.

Meanwhile, in societies with access to vaccines, the resistance to inoculation of large swathes of the population is another concern. This is the case for most eastern European countries, including Russia. The major differences between regions and ethnic groups in the United States could be another worthwhile field of study. One of the novelties of 2022 may be that African countries are given access to vaccines, but their populations are reluctant to be jabbed. It is indicative that Kenya has begun introducing very strict restrictions against the unvaccinated. In most cases, vaccine reticence is a combination of the politicisation of the vaccine, the distrust of institutions, the cut-through of disinformation campaigns, and the strength of the anti-vaccine movement before COVID-19.

Should the health situation become more complicated, the issues that have shaped the global health agenda over the past two years will reemerge. If access problems are blamed, the focus will return to patent liberalisation and vaccine hoarding by more developed countries. If, on the other hand, the dangers to global health emerge in countries where vaccines face public rejection, the pressure to tighten measures or make the vaccine mandatory will rise. With many measures affecting the population as a whole, tensions may increase between those who are vaccinated and those who refuse to be.

From a strictly health point of view, we should be better placed to face new variants with fewer sacrifices than in the early phases of the pandemic. First, because we know which measures work and which do not and, above all, because of the advances in both research and industrial production. The counterpoint is that healthcare systems and professionals are under extreme strain and can hardly withstand greater pressure.

Another health concern for 2022 is that the effects will begin to emerge of having devoted such a large proportion of resources to tackling COVID-19 at the expense of other diseases. This is an issue for both the most developed countries and those with fewer resources. In the case of cancer, for example, a study found that in Spain cytologies had decreased by 50% and visits to patients by 20%. Meanwhile, mental health deterioration is a global phenomenon. In less developed countries, disturbing upswings have been reported in rates of tuberculosis, sexual and reproductive health problems and school-age children affected by intestinal diseases. The hope in this area is that some of the reinforcement of universal healthcare systems will be permanent; that there will be greater pressure to reform international cooperation mechanisms such as the WHO, which proved to be indispensable yet insufficient; and that public and private investment in innovation will continue to bear fruit beyond the fight against the coronavirus.

Fears

The fear of the pandemic has not disappeared, but it must share the stage with other fears. Some, like scarcity and supply chain disruption, are temporary. Others are more permanent in nature, like the consequences of climate change, social discontent and the obsolescence of certain types of training and jobs – according to a study by PWC 39% of employees believe that their job will be obsolete in five years’ time. This, in short, is the fear of being unable to adapt personally and collectively to a series of irreversible transformations. Meanwhile certain actors and interests feed and stoke fear, instrumentalise it politically, or take advantage of it economically. These practices and their effects on social cohesion will be clearly visible in 2022.

If the fight against the pandemic is successful, 2022 could be a year of excitement, of turning the page. But even in that scenario the trauma of the health crisis will have left fertile ground for the politics and economy of fear. The restrictive measures imposed as a result of the pandemic will be subject to intense debate. Their sustainability and the thresholds at which they should be lifted will be particularly discussed, with each regional and national debate having its own nuances and intensity. Certain sectors and interests will seek to extend some restrictions indefinitely in order to tackle other problems with public order, border control and even to fight their political opponents. In this regard, Amnesty International has warned that the fight against the pandemic is widening the global gaps in respect for human rights, while Human Rights Watch has denounced new abuses of freedom of expression. Nothing suggests that those who have supported these control mechanisms during the health emergency are ready to loosen their grip.

Fear goes hand in hand with distrust and feeds on legitimate worries about being left behind. There is distrust of the “other”, especially social groups that compete with, challenge or modify the status quo. There is distrust of institutions that should by nature belong to everyone but which some believe are held captive by a social group to which they do not belong. Science is not immune to this suspicion – for some it is the “science of others” and, for many, distrust of the vaccine is actually distrust of the system. All of this foments populism, racism and hate speech. Meanwhile profits will continue rising for those investing in what was already being called surveillance capitalism before the pandemic and for those who profit from panic buying as was the case in China at the end of 2021.

Reactionary thinking and attitudes will continue to gain strength. The complaint that life was better in the old days will be deployed to question some of the current processes of modernisation and the agenda of emancipatory movements such as feminism. This is nothing new. However, the health crisis and, above all, the acceleration of change have increased both feelings of vulnerability and the conservative attitudes of those who fear losing privileges. Chile’s constitutional plebiscite, amidst a context of strong political and economic polarization, is one of the scenarios of this clash.

Terrorism is another political instrumentalisation of fear that will remain with us in 2022. Whether the pandemic has changed how terrorist groups act or recruit in any way remains unknown. That the threat is increasingly diverse is more certain. On the one hand, this is because jihadist terrorism is operating in increasingly wide areas. In particular, it is spreading in several countries of Sub-Saharan Africa such as the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mozambique. On the other hand, there is the threat posed by far-right terrorism and white supremacism.

This combination of legitimate fears and the partisan use of them strains democratic systems, especially liberal democracies. But it also affects countries that were immersed in political transitions like Tunisia and Sudan. It is possible that this harassment will lead democratic societies to become more aware of their fragility and, therefore, of the need to strengthen themselves, to fight back against those who feed these fears and to better connect with citizens’ aspirations. This is also an invitation to engage with a solidarity agenda at multiple levels, with the aim of inclusively easing the concerns of broad swathes of the population and breaking the spiral of fear and distrust.

Leaderships

Who will allay the fears? Who will manage the climate, digital and social transitions? What kinds of ideas, people and models enjoy most support and legitimacy? We will learn more about these questions from two sources in 2022. First, citizens will give their opinion of the handling of the pandemic at elections. And, second, we will see which ideas, people and models generate most credibility to drive the post-pandemic. It will not only be democratic leaders who seek to reestablish public trust this year; authoritarians will also invest efforts to consolidate their support bases and improve their international reputations.

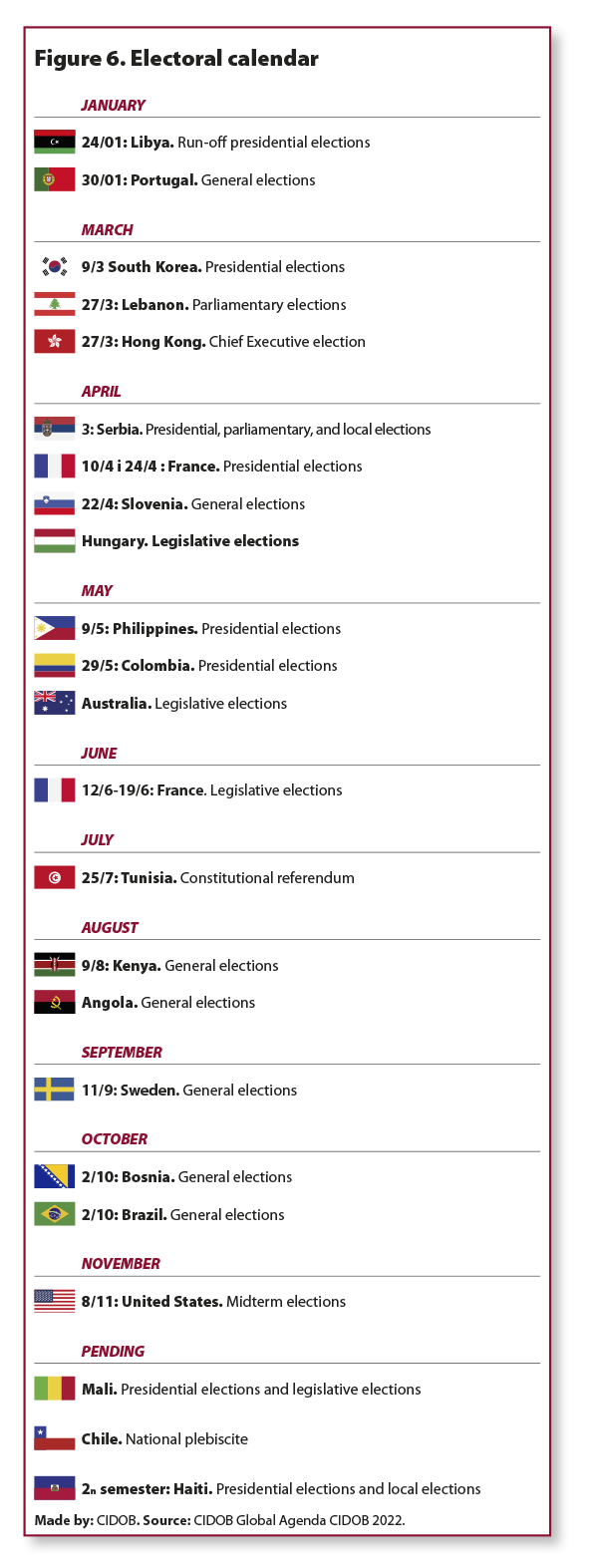

By a quirk of the electoral cycle, 2022 will see several markedly populist leaders facing re-election. In Europe, the list includes the illiberal figures of Viktor Orbán (Hungary), Janez Jansa (Slovenia) and Aleksandar Vučić (Serbia). In Latin America, the focus will be on the Brazilian elections. Jair Bolsonaro not only seeks re-election against former president Lula da Silva, he is preemptively calling the electoral system into doubt, following Donald Trump’s script from 2020. In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte may not be eligible for a new term, but Dutertismo will play its part in the May 2022 elections. The campaign seems likely to have a coarseness that bears his stamp. Not least because he has announced that he will be standing for election to the senate and because his daughter Sara is the vice-presidential candidate on a ticket with Bongbong Marcos, son of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. In India, several regional elections are scheduled. Those in Uttar Pradesh, a state with 200 million people, may give a good measure of Narendra Modi's popularity. In Turkey and Poland rumours of early elections will also resurface, amid doubts over whether calling them is too risky for their current leaders, given the economic crisis facing the former and the political turmoil in the latter.

The ghost of populism will also hover over November's US midterm elections. All 435 members of the House of Representatives will be chosen and 34 of the 100 senators. What level of support will the acolytes of Trumpism be given? With the popularity of President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris down at around 40% in November 2021, speculation will mount not only about whether Trump will run again in 2024, but whether he or one of his acolytes could win.

French citizens have four appointments with the ballot boxes in May and June 2022, as the two rounds of the presidential elections are followed by the parliamentary elections. And as with the 2017 elections, there is the potential for a surprise. The emergence of Éric Zemmour – who Steve Bannon calls an “interesting” candidate – is already setting the tone and content of the political debate. Whether a cordon sanitaire will be implemented if it goes to a second round, as has been the case with Marine Le Pen's party, remains unknown. Macron is confident of re-election against any internal opponent and will look to diversify his bilateral alliances. The French president also aspires to consolidate his leadership of the European Union, especially with Angela Merkel gone. Key to this will be the smooth functioning of a revived Franco-German motor following the formation of the traffic light coalition in Berlin. The appointment of Social Democrat Olaf Scholz as the new German chancellor and the Green foreign affairs minister Annalena Baerbock’s unequivocally pro-European stance and defence of human rights and the fundamental freedoms of the EU have raised expectations in Brussels. Collectively, the EU will have to show it has the capacity to respond to the judicial challenge posed by Poland, the UK's manoeuvring over the Northern Ireland Protocol and control of the English Channel, and turbulences in the Eastern and Southern neighbours.

In terms of leadership, the other big event is the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, which will take place in October. Xi Jinping aspires to consolidate his leadership and control of the party with a third term that would mark the beginning of a new era, breaking with the power alternation system introduced by Deng Xiaoping. Once it is done revising the party’s history, the congress is expected to shore up Xi's position, refresh the party leadership and produce a road map for the coming years to guide towards achieving “common prosperity” at the domestic level. An interesting factor with potentially global impact is the questioning of GDP growth as an indicator of success. In a period shaped by the dual slowdown of the Chinese and global economies, guaranteeing stability, economic progress and the reduction of inequality will be essential to strengthen the legitimacy of both leader and system in the eyes of the public, especially given the private debt crisis, supply problems and widening inequalities. The hundred-year-old party’s legitimacy is essential to consolidating its model of state capitalism and keeping the increasingly powerful business conglomerates at bay.

In Arab countries, several authoritarian leaders will pursue validation. Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman hopes to move on from the reputational crisis provoked by the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 and failed bets like the war in Yemen and the boycott of Qatar. In 2022 the young prince will continue preparing the ground for succession in the event of the death or abdication of his father and will seek to parlay oil production into an improved reputation. Egypt's president, Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, is also seeking to retain power using an intense image rehabilitation campaign and some timid decisions to ease the crackdown on critical voices. Egypt is to host COP27, saying it does so on behalf of Africa. But the fight against climate change will not be al-Sisi's only priority. Holding the conference in Sharm el-Sheikh is not without risks, as it may lay bare the contradictions in terms of freedom of expression and demonstration that emerge every time a COP is held. In Tunisia, President Kais Saied will seek support through popular consultations and a constitutional referendum to legitimize the coup de main given in the summer of 2021 with the dissolution of the parliament, which raised doubts about the survival of the region’s only democratic transition.

Innovations

Are we better prepared for a new way of doing things? Time will tell if the reassessment of the priorities of public administrations and societies that occurred in the pandemic has lasting effect. The measures imposed to tackle the health emergency accelerated processes of economic and social transformation. Readjustments may occur when it comes to teleworking, but the change of habits that has taken place in mobility, consumption and information processing and the intensive process of learning digital tools will be difficult to reverse. Another of the legacies of the health crisis has been the focus on science. Ostensibly contradictory phenomena have emerged. Science’s social prestige has grown (the latest global State of Science Index (SOSI) suggests that 79% of people believe that science will improve life in the next five years), but so have the dynamics of politicisation and contestation mentioned above.

If this trend continues it may have a densifying effect, with more collaboration projects between research teams, alliances forming between public administrations, scientists and the private sector, and a closer relationship between the public and science. Meanwhile, science budgets will be notably larger: the Next Generation EU funds allocate 37% and 20% to financing the green and digital transitions, respectively, while the US stimulus plans will spend $250 billion on innovation.

On the other hand, this will exacerbate the concentration of scientific production in just a few countries. Global investment in artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum computing is led by the United States, China and a small group of developed countries, as well as India in certain fields. When it comes to new patents China is the undisputed leader and a wider shift towards Asia is underway. This scientific asymmetry adds a new dimension of inequality to a world advancing at multiple speeds, even in innovation.

Alongside health, the environment is the second major field where efforts are being concentrated. In 2022, pressure will rise on scientific communities, businesses and public administrations to find innovative solutions to the climate crisis. This includes research into advanced technologies to reduce emissions associated with energy use, such as carbon capture and storage, small modular nuclear reactors and options for decarbonising energy-intensive industries. Another challenge is the search for technical solutions to anticipate and prevent the worst impacts of natural disasters and increase resilience.

Somewhat short-sightedly, in 2022 the energy conversation will continue to revolve around fossil fuels and the geopolitical use of gas. Those with longer-term perspectives will draw attention to the issues around rare minerals and the more abundant lithium, which are essential in the construction of wind turbines, photovoltaic panels, and batteries. The EU seems to be starting to recognise the importance of this issue with actions planned for 2022 such as the operationalisation of the European Raw Materials Alliance and the Batteries Regulation proposed in 2020, which promotes recycling.

In digital matters, chips will remain on the agenda. The chip shortage was a key news item in 2021 and had tangible impact on other industries, as well as on governance and conceptual innovation. 2022 is a year that will test the ambition and usefulness of the EU–US Trade and Technology Council, whose agenda includes artificial intelligence, green technologies, data governance and the global semiconductor supply chain. In conceptual terms, an idea that will gain traction is that of the twin transitions (green and digital), in which cities will play an important role. A common challenge will be the digitalisation of the public sector – a process that has accelerated with the pandemic – and different administrative tiers will seek to identify and emulate successful examples from other countries. Two risks will emerge: administrations being left behind and increased cybervulnerability.

At the intersection between the processes of digitalising the economy and the need to finance post-pandemic stimulus programmes, fiscal solutions will be a topic of rising importance. 2021 was a turning point, among other reasons, due to the commitment made at the G20 summit in Rome to apply a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%. In 2022 these decisions will need to be implemented. New debates about raising the level may also emerge if there is growing public debate about tax justice and the accountability of the fortunes and the power of the founders and main shareholders of large global companies. The latter group reflects the rise of digital, with the world’s rich lists increasingly filled with so-called “tech billionaires” whose business models benefit from their access to “tax optimisation” mechanisms.

The search for these fiscal solutions is part of a broader social agenda that also includes fundamental issues such as intergenerational solidarity and territorial cohesion. Amid profound transformations in the job markets phenomena coexist such as the fight for dignified jobs and the so-called great resignation of 2021. It is therefore worth reflecting on what social, labour and territorial solutions may be incubated in 2022.

Large metropolitan areas face the challenge of combatting inequality at the same time as environmental degradation. Urban interventions to test innovative climate solutions have proliferated over the past two decades thanks to the support of city networks such as C40 and other knowledge-sharing platforms. Cities are becoming the leaders of what is called “government by experiment”: processes that test new socio-technical and governance climate solutions in urban labs and, if successful, scale them up. However, the undisputed pre-eminence of the urban is contrasted by the warning cry of areas with sparser populations and poorer connections – especially in countries with major demographic contrasts. For these areas, the costs of lagging behind in ongoing transitions pose an existential threat. They will look to rebalance their lack of economic muscle through social demands and political action.

In 2022, as well as solutions, talk will turn to the obsolescence of the current models of production and consumption. At the international level, a particularly relevant question is whether the new models of production, consumption and work can be applied universally or whether they deepen processes of fragmentation. The delicate balance between the need to find cooperative solutions and the competitive instincts of the powers aspiring to spearhead these processes of change will also shape the geopolitics of innovation. The space race and anything else seen as "the final frontier" will rise up the agenda.

Mobility

International mobility will be a significant factor in 2022, as the prospects of economic recovery, geopolitical tensions, the politics of fear and the polarisation of the electoral debate in countries such as France, Hungary and the United States all contribute to placing it centre stage. This will materialise in five phenomena of varied nature.

The first is that vaccination levels should mean that 2022 is the year of the great return to international travel – at least for the minority able to afford it before the pandemic, for whom border obstacles should be removed. To grasp the significance of this recovery, it is worth recalling that between April and May 2020 the number of passengers on international flights plummeted by 92% and that the peak of the global mobility restrictions and border closures was reached in December of that year, according to a report by the International Organization for Migration and the Migration Policy Institute. The recovery in 2021 was partial and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has warned of losses of up to 4 trillion in the tourism sector. Depending on how the pandemic evolves, international mobility restrictions will either be reimposed or eased. Leading tourist destinations will compete to prove that their countries are not only attractive but also safe from a health point of view. Agreements on the reciprocal recognition of health documentation – a COVID pass or other formats – will rise up the diplomatic agenda in 2022, especially for countries for which international mobility is essential to their economic development or their reputation. Once again, the pattern of a world that advances at various speeds will be further cemented.

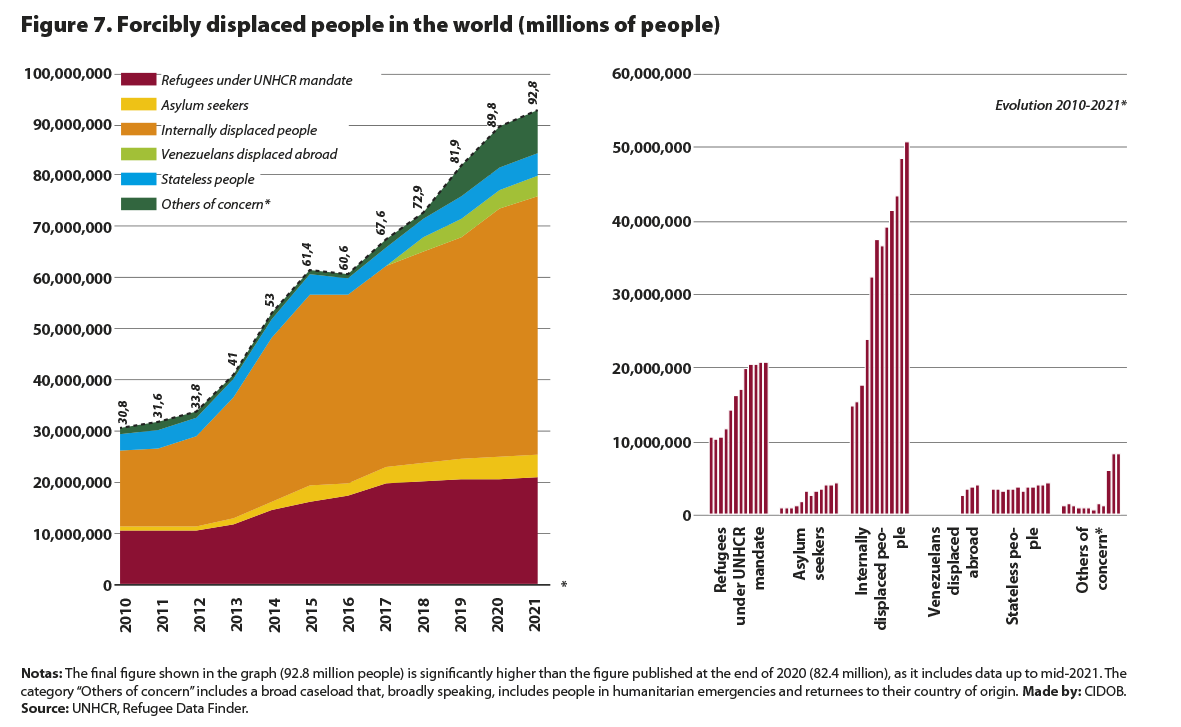

The second is that the measures imposed to contain the pandemic will increase the number of people looking to emigrate. Many of what migration experts call push factors have become almost structural: chronic conflicts, recurrent humanitarian emergencies, more frequent natural crises and rising numbers of new poor. Projecting current trends into the near future suggests that in the coming years the number of forcibly displaced people could reach 100 million (see figure 7). The measures put in place to contain the pandemic have increased the vulnerability of people in need of international protection and exacerbated the phenomenon of cascading crises. Meanwhile, actions that were in vogue pre-pandemic like building physical walls and outsourcing borders will continue to be used, highlighting the contradictions of those, like the Biden–Harris administration, who promised to manage migration flows in a different way.

A third factor is that the health crisis and the imbalances in restarting the economy have caused greater demand for workers in the main developed economies in sectors such as health and social care and transport, among others. So even as borderisation continues, the economic pressure to extend legal emigration channels is rising. Potential beneficiaries are limited to certain professional profiles that do not always fit the traditional description of “highly qualified”. The European Parliament, for example, voted on a resolution in November 2021 requiring the Commission to present a proposal before the end of January 2022 to facilitate the entry of migrants through legal channels in order to resolve the mismatch between supply and demand. Without such action, the resolution states, the European Union will become less attractive and competitive, while the benefits of introducing these measures would add an estimated €37.6 billion to the EU's GDP each year. As in other developed economies, an instrumental and interests-based migration policy will take precedence in the EU over alternative policies of a normative nature, leaving people in need of international protection sidelined.

Fourth, the World Cup in Qatar will place the spotlight on the rights and conditions of foreign workers. Qatar is a paradigmatic case because about 90% of its residents are foreigners and have been essential in building the infrastructure needed to host the World Cup. This sporting event is the culmination of a Qatari policy of projecting influence through soft power mechanisms. It will also reinforce the sense that it has emerged unscathed from the blockade that several Arab countries imposed on it between 2017 and 2021. While the predicament of foreign workers leaves much to be desired, the Qatari authorities are aware of the reputational risk that may be caused by campaigns that have even called for boycotts. As Amnesty International said at the end of 2021, time is running out for Qatar to keep its promises and repeal or substantially reform the kafala (sponsorship) system that gives employers enormous power over employees. Other Middle Eastern countries with similar systems will keep a close eye on the ambitions of any reforms, as will the countries of origin of most of the Gulf’s foreign workers, like the Philippines, Pakistan, India and Nepal.

The fifth factor is the processes of emulation and learning in the political use of migration. European borders are the laboratory at which various countries are testing the limits and exerting pressure on the EU via the fear or public rejection of migrant arrivals, knowing that it is one of the most effective mechanisms for undermining governments and changing priorities. The EU's neighbours are watching and drawing lessons on which tactics work best. As far back as 2010, Kelly M. Greenhill was already describing the phenomenon of “weapons of mass migration”. What is new in this case is that the EU and its member states are also modulating their responses according to the experience accumulated.

Mobility will be a major issue around the world, but its importance will particularly increase in certain border areas. Spain is one such case, particularly when it comes to the two autonomous cities, Ceuta and Melilla. For years the border between Spain and Morocco has been a testing ground for policies and practices and what happens there ends up setting standards for the EU’s other external borders. In 2022, two significant decisions are on the table: when and how Morocco will reopen its borders, and whether a request is made to include the two autonomous cities in the Schengen Area.

Humanitarian crises

In 2020 and 2021, global humanitarian needs grew fast. According to the United Nations, between 2020 and 2021 the number of people in need of humanitarian aid rose from 167 to 235 million. In other words, from one in 45 people in the world to one in 33. COVID-19 is acting as an aggravating factor for pre-existing humanitarian crises. The pandemic also diverted attention from these major crises toward other dramas that are closer at hand, in which rich and middle-income countries have seen their health systems come dangerously close to collapse.

While international funding levels were maintained in 2020 and much of 2021, they remain insufficient given the magnitude and volume of needs. One issue that could worsen an already complicated situation is the rapid and sustained rise in staple food prices. As 2022 approaches, warnings have been given that the food insecurity situation has reached “unprecedented catastrophic levels”.

This short-term factor adds to long-term trends such as the re-emergence of frozen conflicts and the intensification of natural disasters and the destruction of habitats and livelihoods. For example, the number of people being forcibly displaced for climate reasons, such as intense rains or persistent droughts, rose by up to 30 million in 2020. Calculations have not yet been made for 2021. There are more humanitarian crises in more places that last longer and affect broader layers of the population.

Not only will there be more crises in 2022, they will also be addressed as more than just humanitarian problems. Their importance on the international agenda will become clear and in the discussion on what measures should be taken to alleviate them, geopolitical issues that transcend the humanitarian aspects will be considered in depth. Among other places, this will be the case in Afghanistan, East Africa and the Sahel, Central America and the Caribbean, Yemen and at Europe’s borders.

When it comes to Afghanistan, the debate principally surrounds what degree of recognition and dialogue should be granted to the Taliban. Since it seized Kabul, the International Monetary Fund and many other agencies and states have suspended Afghan authorities' access to economic funds. Eighty percent of the previous Afghan government’s budget depended on international funding and, according to World Bank data, over 40% of the country's GDP is Official Development Assistance. The decision of whether or not to work with the new authorities in Kabul will be taken by international organisations, but it will largely depend on the Taliban’s actions and gestures during their first months in power. In September 2021 the UNDP published a report setting out several scenarios for Afghanistan in 2022. At best, the country would lose between 3.6% and 8% of its GDP, with poverty levels rising between 7% and 15%. In the worst-case scenario, with a harsh crisis and international trade disrupted, GDP would fall by over 13% and 97% of the Afghan population would fall into poverty. Faced with the risk of the Afghan state and economy collapsing, humanitarian aid – channelled through the United Nations or a country with open channels to the Afghan government – may prove to be even more essential.

The humanitarian situations in several African countries will deteriorate in 2022. With very high levels of pre-existing poverty, some of the world’s worst famines and access to health and education services, some parts of the continent, such as the Horn of Africa and the Sahel, are also seeing violence rise and frozen conflicts thaw. Of particular concern is the war between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People's Liberation Front which, among other effects, is preventing humanitarian aid from reaching several regions of northern Ethiopia, propelling the number of people in need of assistance to over eight million and contributing to levels of famine unseen in recent decades. To this must be added the “hydropolitical” tensions between Addis Ababa and Cairo over the flow of the Nile, the chronic violence in South Sudan and parts of Somalia, the uncertain succession in Chad, the political instability in Mali, Africa’s largest crisis of internally displaced persons in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the spread of jihadist terrorism from the Sahel to northern Mozambique, where over 800,000 people have been displaced following the establishment of another jihadist group.

The humanitarian situation is also deteriorating in several areas of Central America and the Caribbean. In 2021 Haiti made the headlines again: political violence (the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse), rising organised crime, natural disasters (the devastating earthquake of August 14th, followed shortly after by a tropical storm) and the controversial deportations of Haitians by the United States, which led its special envoy to resign. As well as Haitians, many other citizens of Central America will be caught up in desperate predicaments, especially those fleeing the poverty of the so-called Dry Corridor and the violence of criminal gangs established in the major cities.

The conflicts in Yemen and Syria may have disappeared from the media agenda, but they remain ongoing and the humanitarian situations continue to worsen. Martin Griffiths, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs, warns that 90% of the Syrian population already lives below the poverty line. At the United Nations Yemen has been described as "not only the worst humanitarian crisis in the world – it is also the worst international response to a humanitarian crisis in the world". One of the paradoxes of these two conflicts is that the gestures of rapprochement made by regional powers do not seem to be lowering the levels of violence, meaning the suffering of civilians caught up in the conflict is not being alleviated.

One of the novelties of 2022 could be that humanitarian crises spread to countries that are not in conflict. The rapid decline in living conditions in Lebanon is ringing multiple alarm bells. The World Bank sees it as one of the world’s worst crises and attributes its severity to inaction. European countries will watch with concern as these humanitarian crises spread and take hold ever closer to their borders, as the irregular migration continues in the Mediterranean – a humanitarian disaster in itself.

Climate emergency

The Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Amor Mottley, began her pointed speech at COP26 by recalling "that the pandemic has taught us that national solutions to global problems do not work". What eventually emerged from the Glasgow summit was somewhat uneven. Politically, there were important gestures: the United States returned to the table after Trump's rebuffals; China was not represented at the highest level – Xi Jinping has not left the country since the COVID-19 outbreak – but it did sign a joint declaration of symbolic value with the United States; Turkey announced its ratification of the Paris Agreement just before the summit; and Modi announced India's commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2070, although without providing concrete details.

However, last-minute pressure from India succeeded in watering down the final resolution on coal power. Efforts would be accelerated “towards the phase down of unabated coal power” rather than the phasing “out” of the previous wording. This sense of urgency and pressure helped ensure the Glasgow Climate Pact was adopted in extra time. The agreement allows the Paris Rulebook to be completed and facilitates its implementation, while also including the commitment to review the national plans for keeping to the goal of 1.5°C in 2022. This commitment will be one of the big issues ahead of COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh. Will these really be new plans that match the urgency of the need or will they be mere revisions? This is a complicated task from a technical point of view and time is pressing.

In Glasgow, rich countries promised more financial assistance to less developed countries. However, the potential recipients still consider it insufficient, among other reasons due to the postponement of the promised $100 billion per year to 2022–2023. The Glasgow Pact is also the basis for starting negotiations on new post-2025 funding targets. Some initiatives agreed by groups of countries on reducing methane gas emissions and deforestation also deserve attention. Among the other new features were the commitments made by groups of companies like the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), the initiative led by the EU and over 100 countries to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030, the commitment by over 100 world leaders to end deforestation – also by 2030 – and the undertaking by the automotive industry and some states, regions and cities to achieve the sector’s global transition by 2040 and five years earlier in major markets. But all these plans remain medium-term. In 2022 we will have to see if concrete measures are taken in the short term and if these types of initiative set examples that are replicated in other areas of economic activity.

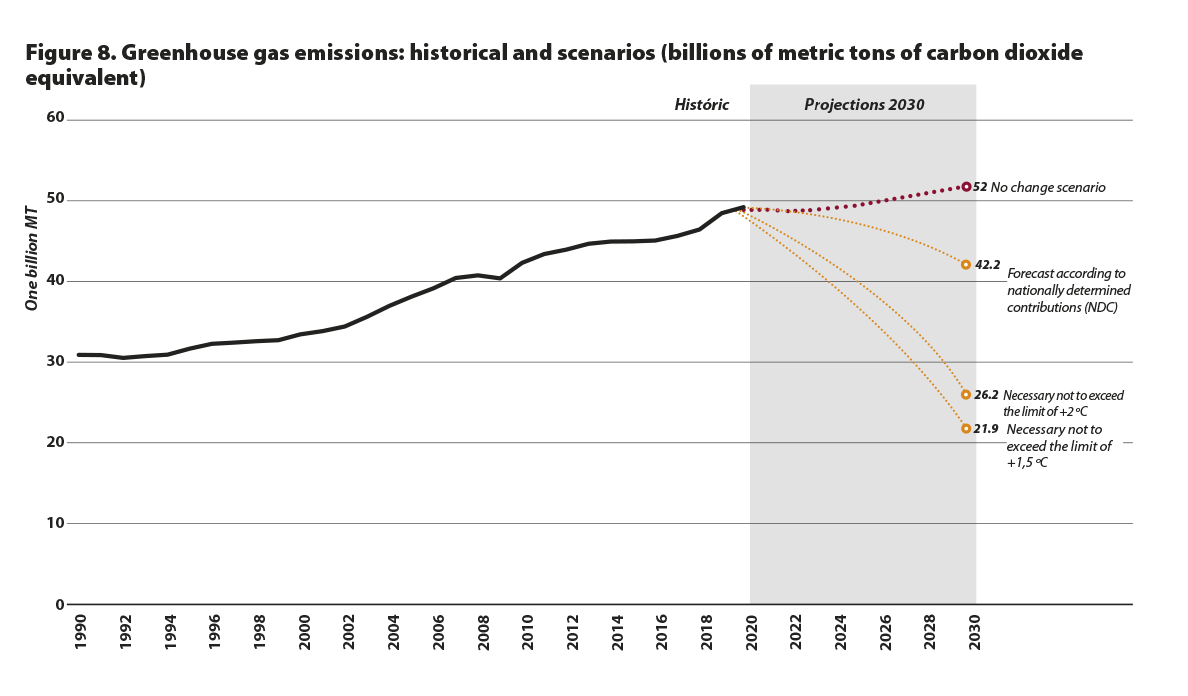

As Joe Biden said in his speech, the coming years are decisive. The US president described this decade as a brief window of opportunity to increase ambitions and get to work, but one which is closing rapidly. He was merely reiterating the consensus in the scientific community on the need to change course before it is too late (see figure 8).

While the political leaders left Scotland with the peace of mind that at least an agreement was reached, climate activists were clearly disappointed. More combative sectors like Extinction Rebellion have announced mass mobilisations in April 2022. Those with more pragmatic positions, like the Race to Zero campaign, see the challenge for 2022 as expanding alliances and commitments. If climate protests return to the streets and offices, it will be worth seeing whether those aggrieved by the energy transition who had begun protesting against environmental taxes or the end of the coal industry in several European countries prior to the pandemic will also raise their voices.

Another of the big themes for 2022 is the preparation of the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and the reactions it provokes among those who feel it harms them. The European Union is leading the way in this area, although debate will continue over the final form of the regulation in 2022. The United States is studying similar measures. Beyond the main objective of mitigating climate change, these initiatives seem to have a dual purpose. On the one hand encouraging other countries to implement climate policies, above all, by taxing carbon. And, on the other, avoiding the delocalisation of polluting industries. Implementation will be gradual – starting in 2023 and being completed in 2026. In the first phase, it will affect large sectors such as the steel, fertiliser and cement industries. It will mean 2022 is a year in which the EU will have to do a lot of pedagogical work with countries that will accuse it of green protectionism, while also negotiating exemptions that do not invalidate the overall system. An early test will be the EU–African Union summit in February 2022.

The concept of justice will be notable at this type of meeting and in the global conversation on the climate challenge. However, the terms of the debate will have different overtones depending on whether we are talking about industrialised countries or the Global South. In the most developed economies, there will be an insistence that a just transition must be promoted that does not aggravate internal inequalities and which compensates sectors, territories and individuals that lose out from the green transition. On the other hand, late-industrialising countries and those with significant development deficits will demand that the countries most responsible for past emissions fund the mechanisms to adapt to the inevitable effects of climate change. This will become one of the focuses of debate at COP27. On the other hand, states that are particularly affected by global warming, such as small island developing states, are insisting on the importance of the loss and damage agenda – in other words, direct compensation.

The environmental agenda resumes at multiple speeds, including backwards. The main risk is that, despite the need for a collective response, perceptions and interests differ too much to prevent an adequate response. The speed mismatch is evident in the green transition but also in relation to the economic recovery, scientific production, mobility and access to vaccines. In last year's exercise, we said that if managing COVID-19 was a kind of examination, we should ask to retake. In this retake, handling a pandemic with some way to run is another factor on top of the climate emergency, the ability to contain and deactivate geopolitical tensions with significant destructive potential and reducing inequalities. On these and other fronts it must be shown that lessons have been learned and that the sense of urgency is being translated from speech to action.

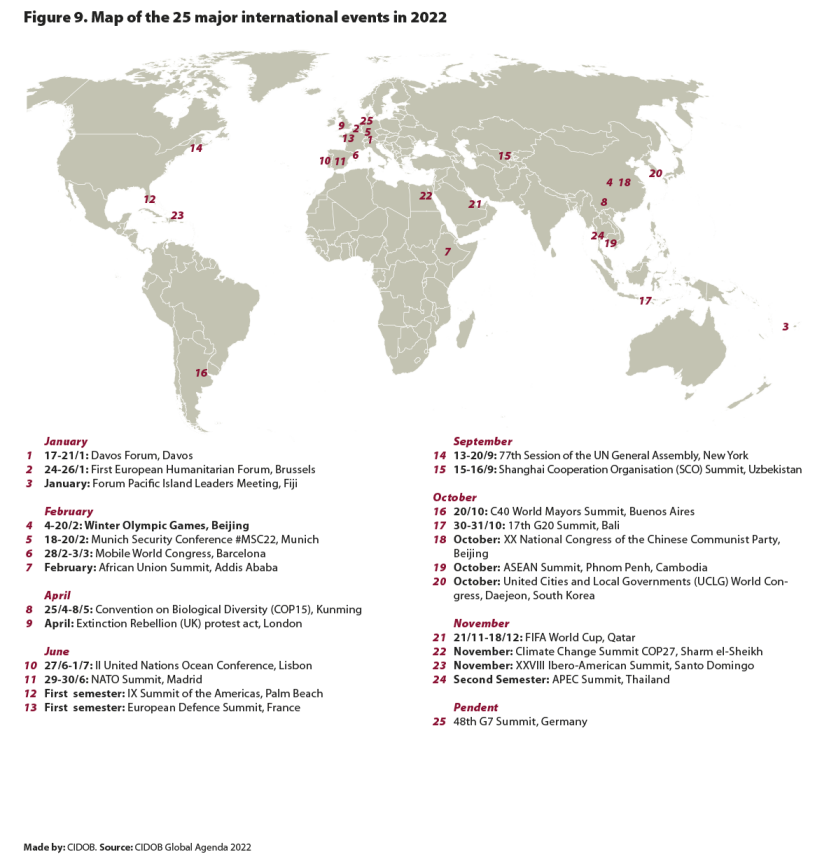

CIDOB Calendar 2022: 75 dates to mark on the international calendar

January 1 - Renewal of the United Nations Security Council. Albania, Brazil, Gabon, Ghana and the United Arab Emirates join the UN Security Council as non-permanent members.

January 16 - 30th anniversary of the Chapultepec Peace Accords. The agreements signed between the government and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) brought an end to 12 years of civil war in El Salvador. A peace process began that pushed through a series of political, judicial and military reforms and was ended by the UN in 1997. The current administration, led by controversial President Nayib Bukele, has questioned the spirit of these agreements, calling them a “farce” and corrupt, drawing a wave of indignation from human rights organisations, war victims, ex-guerrillas, etc.

January 17–21 - Davos Forum. Annual event attended by the major political leaders, senior executives of the world’s most important companies, heads of international organisations and NGOs, and notable cultural and social figures. The theme this year is "Working together, restoring trust" and it will analyse the global economic recovery from the pandemic and the rise of social tensions.

January 23-27 – Fifth United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries. Qatar hosts the multilateral forum with 46 participant countries. It is expected to adopt a Programme of Action to 2030, with post-pandemic recovery the top priority.

January 24 - Second round of Libyan elections. A number of candidates will compete to reach the second round of the presidential elections promoted by the United Nations, among them Khalifa Haftar, leader of the self-styled Libyan National Army, which controls the country’s east and parts of the south, former Interior Minister Fathi Bashagha, the prime minister of the interim Government of National Unity, Abdulhamid al-Dbeibah, and Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, son of Muammar Gaddafi. The country seeks a political solution after ten years of armed conflict.

January 24–26 – The first European Humanitarian Forum. Organised by the European Commission and France – president of the Council of the European Union for the first half of 2022 – this event will bring together policymakers, humanitarian organisations and other partners to address the urgency of humanitarian aid and the constraints facing the organisations and their beneficiaries

January 30 - General elections in Portugal. After the budget was rejected by the Communist Party and the Left Bloc, António Costa’s government fell, bringing an end to six years of political stability.

January 30 - 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. In Derry (Northern Ireland) in 1972 – during the period of “the Troubles” – a march against a law introduced by the British government ended with the army opening fire and 13 people dead. The riots that followed led to the dissolution of the Belfast parliament, the British embassies in Dublin and Northern Ireland being set alight and recruitment surging for the IRA terrorist group. It took until 2010 for then Prime Minister David Cameron to apologise on behalf of the British government.

January - Pacific Islands Forum. Oceania’s main pan-regional forum sees 18 states and territories come together to discuss climate change, the sustainable use of maritime resources, security and regional cooperation. This year’s meeting comes amid growing tensions between China and the United States and their allies.

February 4–20 - Winter Olympics. China hosts the 24th winter games in Beijing. It will be affected by the global impact of COVID-19, issues with international mobility and the threat of a diplomatic boycott by several countries as a means of denouncing Chinese human rights violations, as well as the controversy over the sexual assault allegations made by tennis player Peng Shuai and her subsequent disappearance.

February 7–11 - First International Conference on Nuclear Law. Austria will host the first conference organised by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for the world’s governments, international organisations, the business sector and civil society to debate nuclear law.

February 17–18 - African Union–European Union Summit. African and European leaders have been working for several years to approve a strategic partnership between the two blocs, which is of particular interest to the EU. Key issues for both sides on the agenda will be the green transition, migration, transnational security and various trade agreements.

February 18–20 - Munich Security Conference #MSC2022. The largest forum for discussing international security policies will gather high-level figures from over 70 countries.

February 28 - Centenary of Egyptian independence. 100 years since Egypt gained independence from the United Kingdom. The celebration comes with al-Sisi attempting to regain international prestige.

February 28–March 3 - Mobile World Congress. Barcelona hosts the largest global gathering of the main international technology and communications companies. This year it will focus on connectivity and reinvention. Particularly awaited are potential proposals on Big Data, 5G, artificial intelligence and other technological advances shaped by the habit changes produced by the pandemic.

February - Italian Presidency. With Sergio Matarella’s term as president ending in February, the process to choose a candidate for the next seven years will start early in January. Among the names mentioned are Prime Minister Mario Draghi and Silvio Berlusconi.

February – Launch of the Artemis mission. The United States will send Artemis I, an unmanned spacecraft, to the moon with the ultimate goal of launching another manned mission to the moon in 2025.

February - African Union Summit. Senegal takes over as chair of the African organisation with multiple fronts open on the continent: the economic and health consequences of the pandemic; the war in Ethiopia; the governance abuses and democratic backsliding on the continent (e.g. in Sudan, Mali, Chad and Guinea); the socioeconomic and governance crisis in Zimbabwe; the violent extremism in northern Mozambique; the tensions between Algeria and Morocco; and the rise in forced displacement and food insecurity on the continent.

February - Legislative elections in Uttar Pradesh (India). The most important of several regional elections. With a population of 200 million, this state is governed by Narendra Modi's BJP and may shape the political cycle between now and the 2024 general elections.

March 9 - Presidential elections in South Korea. The country votes with geopolitical tensions high in the Indo-Pacific and with former prosecutor general Yoon Seok-Youl looking to unseat the current president Moon Jae-in, whose government has fallen in the polls following several cases of corruption, rising house prices and growing social unrest.

March 19 - 60th anniversary of Algerian independence. French colonisation may have ended six decades ago, but diplomatic frictions rose between the governments in Paris and Algiers in 2021 for reasons to do with historical memory.

March 27 - Parliamentary elections in Lebanon. Mired in a deep institutional and economic crisis and an emerging domestic humanitarian crisis, Lebanese citizens go to the polls.

March 27 - Elections in Hong Kong. Carrie Lam’s term ends as Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), although she may be eligible for renewal. Following the mass protests of 2019, the introduction of a national security law and a new electoral system, social tensions in Hong Kong remain high. These elections will also take place on the 20th anniversary of the transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom to China.

March - Approval of the Strategic Compass. The EU will approve the Strategic Compass, a document that aims to define the European foreign policy strategy and identify security and defence threats and risks.

April 3 - Presidential, parliamentary and local elections in Serbia. Aleksandar Vučić's populist and conservative Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) has dominated Serbian political life for years. These elections also take place after several months of friction between Serbia and Kosovo, which forced the EU to step in and mediate.

April 10 and 24 - Presidential elections in France. Emmanuel Macron seeks a second term in elections that, barring surprises, will be decided in a second round. Éric Zemmour’s abrupt emergence as a presidential candidate will further polarise the electoral campaign, with public debate centring for months on immigration, security, geopolitics and historical revisionism.

April 22 - General elections in Slovenia. Janez Jansa, current prime minister and leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party, hopes for a renewed mandate. His government must face both the European authorities and major domestic social protests over some of the measures adopted since he took office for the third time in 2020. Four of the main opposition parties have reached a coalition agreement if they win the elections.

April 25–May 8 - UN Conference on Biodiversity (COP15). The goal of this second part of the conference, which began virtually in October 2021, is to finalise and adopt the post-2020 global biodiversity framework in order to stabilise trends that have exacerbated biodiversity loss.

April - Legislative elections in Hungary. The independent Péter Márki-Zay will be running against Prime Minister Viktor Orbán for the unified list of six Hungarian opposition formations, which covers a wide political spectrum. Hungary's relationship with the European Union will be one of the campaign’s key themes, along with security and immigration.

April - Completion of the CoFoE. In May 2021, the European Commission, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union launched a series of citizen consultations to gather ideas on the challenges and priorities for the European project for the coming years. The conclusions are expected to be made public in April and tangible orientations and proposals will be provided at the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFoE).

April - Extinction Rebellion protest (UK). Extinction Rebellion, the non-violent environmental civil disobedience movement, has announced its intention to carry out the largest act of political resistance in UK history to demand effective environmental policies from governments and the international community.

May 9 - Elections in the Philippines. Sara Duterte-Carpio, daughter of President Rodrigo Duterte, and Ferdinand Bongbong Marcos, son of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, are running mates for the country’s vice-presidency and presidency, respectively. Another notable candidate is Philippine boxing legend Manny Pacquiao, a former ally and current political rival of Rodrigo Duterte.

May 26 - 50th anniversary of the SALT 1 Treaty. The first major treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union to limit the number of anti-ballistic missiles used in defense against nuclear-armed missiles.

May 29 - Presidential elections in Colombia. With the signing of the Peace Accords between the government and the FARC in 2016 a new political and social landscape opened up in Colombia. Three major political alliances, whose candidates will be chosen in the coming months, aspire to win the presidency: the leftist Pacto Histórico, the Centro Esperanza Coalition and the right-wing Equipo por Colombia. The general elections two months earlier on March 13th will act as a barometer of the strength of each coalition.

May - Parliamentary elections Australia. The centre-right Liberal/National coalition, in power since 2013, will be challenged by the Labour party, which is putting the environmental agenda at the centre of the political debate. Australia's role in the geopolitical chessboard of the Pacific will give this election campaign a greater international relevance.

June 12-June 19 - Legislative elections in France. Cohabitation will be the spectre hovering over the elections to decide the makeup of the National Assembly. If it turns out to be hostile to the President of the Republic, the latter could see their room for manoeuvre restricted, particularly on domestic policy.

June 17 - 50th anniversary of Watergate. Considered the largest political scandal in US history, during the 1972 electoral campaign the Nixon administration was caught engaging in espionage after a break-in at the offices of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate building complex in Washington.

June 20 - World Refugee Day. The number of people forcibly displaced in 2021 once again reached record numbers, both in terms of the internally displaced and refugees. During this week of June the UNHCR will publish its annual report on the trends in forced displacement around the world.

June 27-July 1 – 2nd. United Nations Ocean Conference. Postponed from 2020 and organised jointly by Kenya and Portugal, this will be one of the year’s key environmental events. Governments, the private sector and civil society will all attend and seek to make progress on achieving the 2030 Agenda’s SDG 14 on Life Below Water, especially in the use of green technology and innovative uses of marine resources, loss of habitats and biodiversity, and ocean governance.

June 29–30 - NATO Summit. Madrid will host the Atlantic Alliance summit. It is expected to adopt a new NATO Strategic Concept and will address security issues in relation to North Africa and the Sahel, its complementarity with European security and the security challenges posed by hybrid and technological wars.

First half-year – 9th Summit of the Americas. The United States will host this summit, which brings together all the leaders of the continent’s countries. On the agenda: migration, climate change, democratisation, security and post-pandemic America. It remains to be seen whether the governments of Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba will participate, as they are in open confrontation with Joe Biden’s government.

First half-year - European Defence Summit. France will host the first European Union summit specifically focussed on defence.

July 5–15 - UN High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. The United Nations’ main platform for monitoring and reviewing the 2030 Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals. This year it will have the slogan “Building back better from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) while advancing the full implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”.

July 25 – Constitutional referendum in Tunisia. A year after President Kais Saied's controversial decision to suspend parliament, Tunisians should give their approval to the new constitution. Before that, a public consultation process will begin and, foreseeably, there will be legislative elections in December.

August 9 - General elections in Kenya. With Uhuru Kenyatta unable to stand after his second term, succession issues are stressing the country. The situation has been aggravated by the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic. The battle for the votes of the nearly 7 million new voters will play a key role.

August 15 - First anniversary of the Taliban’s return to power. A year since the fall of the Ashraf Ghani government and the Taliban proclaimed the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

August - General elections in Angola. The People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) – in power since 1979 – hopes to revalidate its control of the executive branch, which is in the hands of President João Lourenço, who faces allegations of authoritarianism and poor governance and internal rivalries in his party. The opposition is grouped behind the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and its leader Costa Júnior.

September 5–6 - 50th anniversary of the Munich Massacre. At the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, the Palestinian terrorist group Black September stormed the Israeli delegation’s rooms and took 11 members of the Olympic team hostage, with two dying in the assault. The other nine died in the following hours after a failed rescue operation.

September 11 - General elections in Sweden. The fall of the governing coalition in November 2021 pitched the country into a period of instability and deadlock. One of the questions to be resolved will be what alliances and new coalitions the parties on the right and the populists will form.

September 13–20 - 77th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. The annual date on which world leaders gather to assess the current state of their national policies and their vision of the world.

September 15-16 - Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Uzbekistan will host a new edition of this regional security and economy forum, which is formed of China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and, more recently, Iran. The forum is gaining prominence on the regional geopolitical agenda.

October 2 - General elections in Bosnia. Bosnia and Herzegovina faces an electoral year with internal tensions growing that risk undoing all the advances made in recent years. The secessionist threats made by Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, which would spell the end of the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement, have raised the heat between the country’s different ethnic communities.

October 2 - General elections in Brazil. Jair Bolsonaro runs for re-election, this time under the umbrella of the Liberal Party. Unless the justice system gets in his way, former president Lula da Silva will stand for election having regained his political rights after being released from prison. A third way could open up in the form of the candidacies of former justice minister Sergio Moro and Ciro Gomes.

October 20 – C40 World Mayors Summit. Buenos Aires will host this edition of C40, which gathers 30 mayors from the world’s most important cities. The meeting will focus on the post-pandemic urban agenda and the implementation of a green agenda.

October 27–29 - Centenary of the March on Rome. 100 years since the March on Rome that brought Benito Mussolini, leader of the National Fascist Party, to power after Luigi Facta’s government fell and King Victor Emmanuel III requested the Fascists form a government. Far-right groups and neo-fascists have announced their intention to commemorate this anniversary. It will be a time to reflect on the vulnerability of liberal democracies.

October 30–31 – 17th G20 Summit. “Recover together, recover stronger” will be the slogan of the 17th summit of G20 leaders to be held in Bali, Indonesia.