The world in 2025: ten issues that will shape the international agenda

Text finalised on December 15th, 2024. This Nota Internacional is the result of collective reflection on the part of the CIDOB research team. Coordinated and edited by Carme Colomina, with contributions from Inés Arco, Anna Ayuso, Jordi Bacaria, Pol Bargués, Javier Borràs, Víctor Burguete, Anna Busquets, Daniel Castilla, Carmen Claudín, Patrizia Cogo, Francesc Fàbregues, Oriol Farrés, Marta Galceran, Blanca Garcés, Patrícia Garcia-Duran, Víctor García, Seán Golden, Rafael Grasa, Josep M. Lloveras, Bet Mañé, Ricardo Martinez, Esther Masclans, Oscar Mateos, Pol Morillas, Francesco Pasetti, Roberto Ortiz de Zárate, Héctor Sánchez, Eduard Soler i Lecha, Laia Tarragona and Alexandra Vidal.

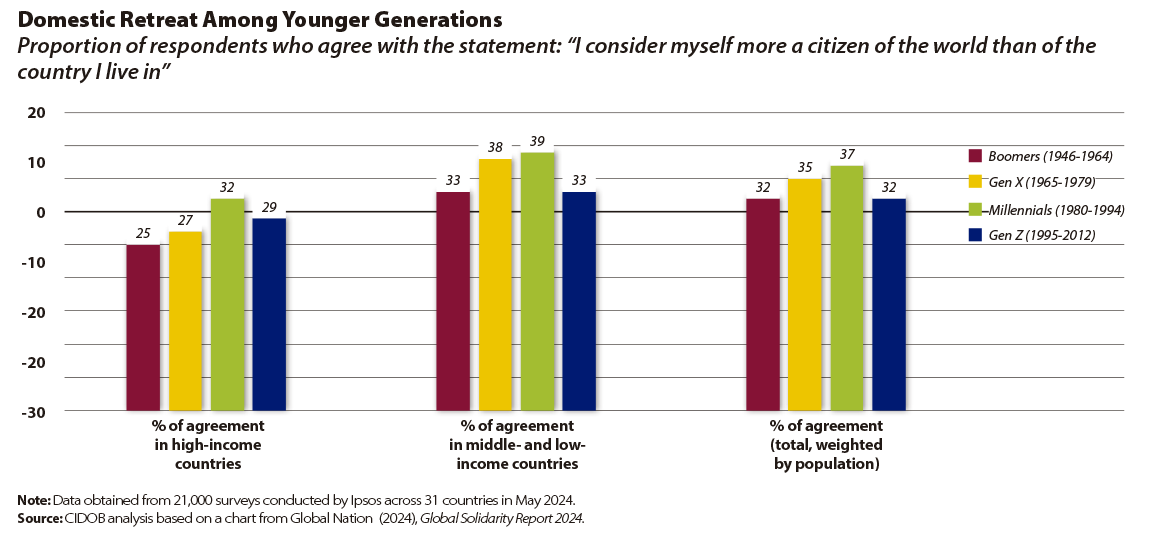

2025 begins with more questions than answers. The world has already voted and now it is time to see what policies await us. What impact will the winning agendas have? How far will the unpredictability of Trump 2.0 go? And, above all, are we looking at a Trump as a factor of change or a source of commotion and political fireworks?

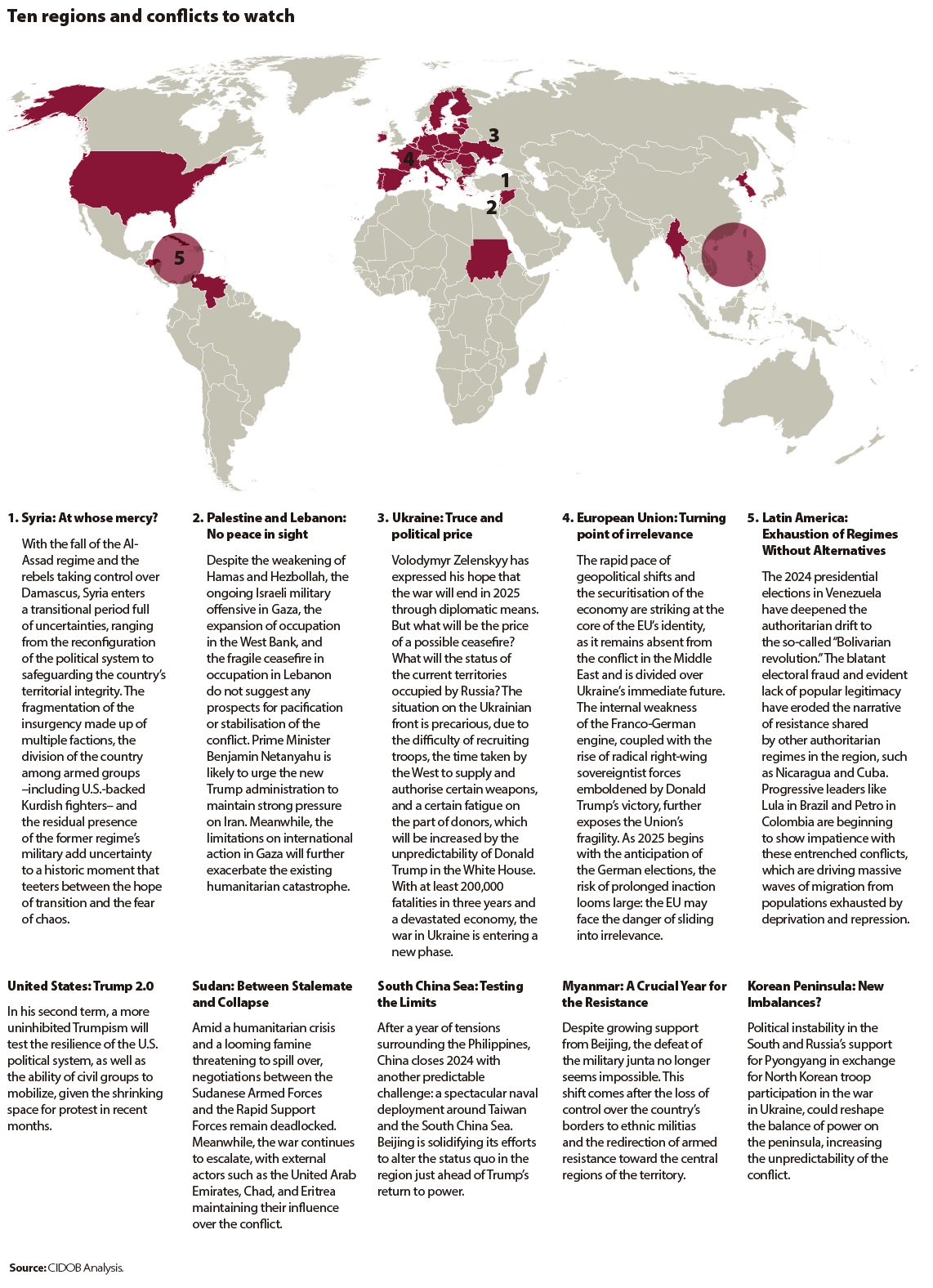

In 2025 there will be talk of ceasefires, but not of peace. The diplomatic offensive will gain ground in Ukraine, while the fall of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad opens an uncertain political transition. These movements will test an international system incapable of resolving the structural causes of conflicts.

The world is struggling with the posturing of new leaderships, the shifting landscapes that are redefining long-running conflicts and a Sino-US rivalry that may develop into a trade and tech war in the near future. Fear, as a dynamic that permeates policies, both in the migration field and in international relations, will gain ground in 2025.

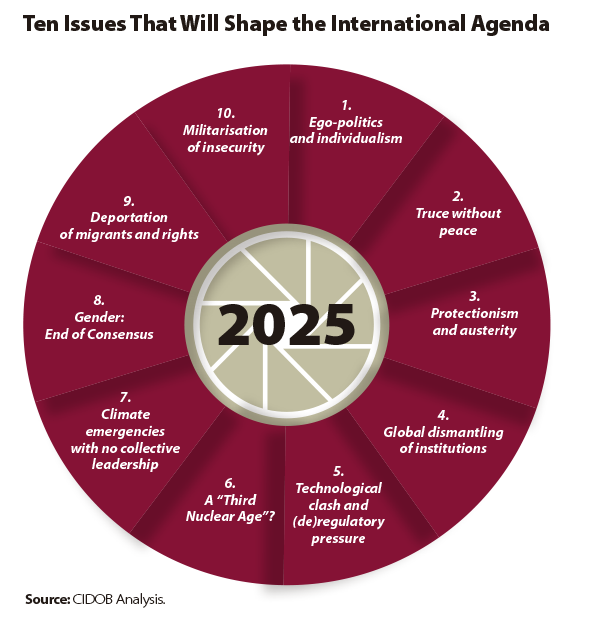

2025 will be a year of post-election hangover. The world has now cast its vote, and it has done so in many cases from a place of anger, discontent or fear. Over 1.6 billion people went to the polls in 2024 and in general they did so to punish the parties in power. The list of defeated rulers is a long one: US Democrats, UK Conservatives, “Macronism” in France, the Portuguese left. Even those who weathered the storm have been weakened, as shown by the election debacle of Shigeru Ishiba’s ruling party in Japan, or the coalitions necessary in the India of Narendra Modi or the South Africa of Cyril Ramaphosa.

The election super-cycle of 2024 has left democracy a little more bruised. The countries experiencing a net decline in democratic performance far outnumber those managing to move forward. According to The Global State of Democracy 2024 report, four out of nine states are worse off than before in terms of democracy and only around one in four have seen an improvement in quality.

2025 is the year of Donald Trump’s return to the White House and of a new institutional journey in the European Union (EU) underpinned by unprecedentedly weak parliamentary support. The West’s democratic volatility is colliding with the geopolitical hyperactivity of the Global South and the virulence of armed conflict hotspots.

Which is why 2025 begins with more questions than answers. With the polls closed and the votes counted, what policies await us ? What impact will the winning agendas have? How far will the unpredictability of Trump 2.0 go? And, above all, are we looking at a Trump as a factor of change or a source of commotion and political fireworks?

Even if the United States today is a retreating power and power has spread to new actors (both public and private) who have been challenging Washington’s hegemony for some time now, Donald Trump’s return to the presidency means the world must readjust. Global geopolitical equilibriums and the various conflicts raging – particularly in Ukraine and the Middle East – as well as the fight against climate change or the levels of unpredictability of a shifting international order could all hinge on the new White House incumbent. The fall of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad opens an uncertain political transition, which reinforces the idea that 2025 will be a year of need for diplomatic processes that accompany the geopolitical rebalancing that may come in the coming months.

We also live in a world still weighed down by the impact of COVID-19. Five years after the coronavirus pandemic, many countries continue to grapple with the debt they took on to combat the economic and social damage of that global health crisis. The pandemic left us a world deeper in debt, one that is more digitalised and individualistic, where the discordant voices among the major global powers have been gaining ground; where climate, economic and geopolitical goals are becoming increasingly divergent. It is a world in which not only policies clash, but discourses too. The old social and cultural fault lines have become more evident: from culture wars to the struggle for control over information and algorithmically inflated bubbles on social media. The elections in the United States, Pakistan, India, Romania, Moldova or Georgia are a clear illustration of the destabilising power of “alternative” narratives.

The US election hangover, then, will not be the type to be cured with rest and a broth. Trump himself will see to ramping up the political posturing as he makes his return to the Oval Office starting January 20th. Yet, above the rhetorical noise, it is hard to distinguish what answers will be put in place, to what extent we are entering a year that will further reinforce the barriers and withdrawal that have turned society inwards and fragmented global hyperconnectivity; or if, on the other hand, we shall see the emergence of a still tentative determination to imagine alternative policies that provide answers to the real causes of discontent and try to reconstruct increasingly fragile consensuses.

1-EGO-POLITICS AND INDIVIDUALISM

2025 is the year of posturing and personalism. We shall see the emergence not just of new leaderships, but also of new political actors. The magnate Elon Musk’s entry into the campaign and Donald Trump’s new administration personify this shift in the exercise of power. The world’s richest individual, clutching the loudest megaphone in a digitalised society, is stepping into the White House to act as the president’s right-hand man. Musk is a “global power”, the holder of a political agenda and private interests that many democratic governments do not know how to negotiate. In this shift in power (both public and private) the cryptocurrency industry accounted for nearly half of all the money big corporations paid into political action committees (PACs) in 2024, according to a report by the progressive NGO Public Citizen.

The last political cycle – from 2020 to 2024 – was characterised by “election denialism”: a losing candidate or party disputed the outcome of one in five elections. In 2025, this denialism has reached the Oval Office. The myth of the triumphant narcissist has been bolstered by the ballot box. It is the triumph of ego over charisma. Some call it “ego-politics”.

Ever more voices are challenging the status quo of democracies in crisis. Anti-politics is taking root in the face of mainstream parties that are drifting ever further away from their traditional voters. Trump himself believes he is the leader of a “movement” (Make America Great Again, or MAGA) that transcends the reality of the Republican Party. These new anti-establishment figures have gradually gained ground, allies and prophets. From the illiberal media phenomenon of the Argentinian president Javier Milei – who will face his first big test in the parliamentary elections of October – to Călin Georgescu, the far-right candidate for the presidency of Romania who carved a niche for himself against all odds, without the support of a party behind him and thanks to an anti-establishment campaign targeting young people on TikTok. He is the latest example of a 2024 that has also seen the arrival in the European Parliament of the Spanish social media personality Alvise Pérez and his Se Acabó la Fiesta (“The Party’s Over”) platform, garnering over 800,000 votes, or the Cypriot youtuber Fidias Panayiotou, among whose achievements to date number having spent a week in a coffin and having managed to hug 100 celebrities, Elon Musk included.

All this also has an impact on a Europe of weak leaderships and fractured parliaments, with the Franco-German engine of European integration feebler than ever. Indeed, the hyper-presidentialism of Emmanuel Macron, who also embraced the idea of the En Marche movement to dismantle the Fifth Republic’s system of traditional parties, will have to navigate 2025 as a lame duck, with no possibility of calling legislative elections again until June. Germany, meanwhile, will go to the polls in February with an ailing economic model, rampant social discontent and doubts about the guarantees of clarity and political strength that might be delivered by elections that have the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD) lying second in the polls.

In 2025, we shall also see an escalation of the political drama in the Philippines between the country’s two most powerful political clans, brought on by the toxic relationship between the president, Fernando “Bongbong” Marcos, and his vice president, Sara Duterte, and which includes death threats and corruption accusations. The return to politics of the former president, Rodrigo Duterte, nicknamed the “Asian Trump”, who in November registered his candidacy for the mayoralty of Davao, and the midterm elections in May will deepen the domestic tension and division in the archipelago. In South Korea, meanwhile, 2024 is ending with signs of resistance. President Yoon Suk Yeol, also considered an outsider who triumphed in what was dubbed the incel election of 2022, faced popular protests and action by the country’s main trade unions after declaring martial law in response to political deadlock. The Korean Parliament has voted to initiate an impeachment process to remove Yoon Suk Yeol and, if it goes ahead, the country will hold elections before spring

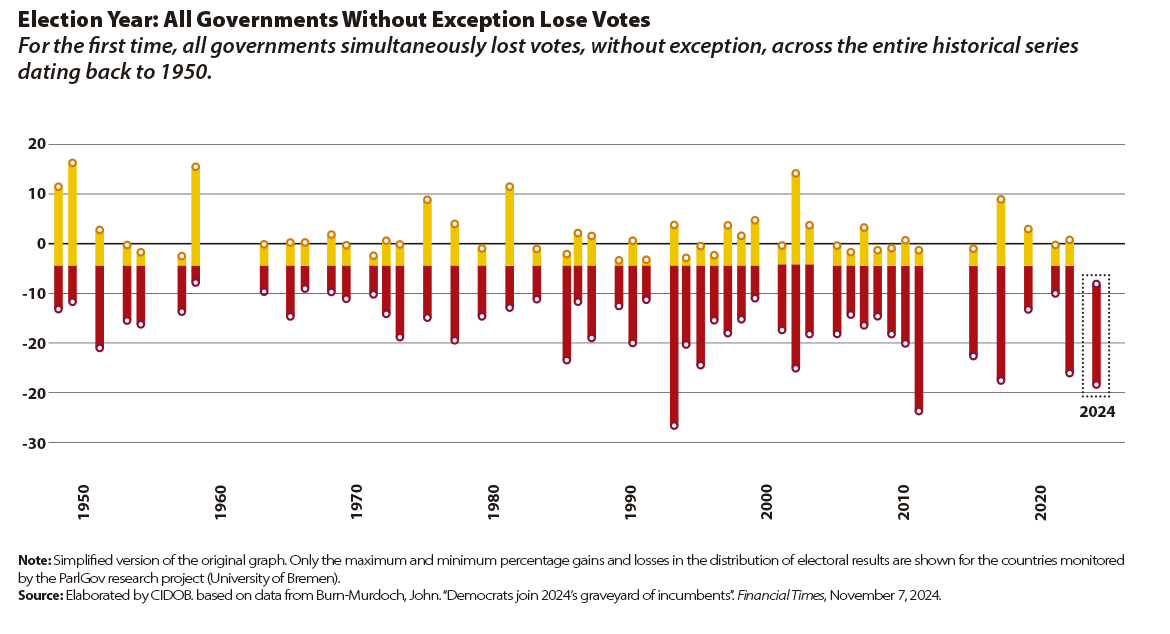

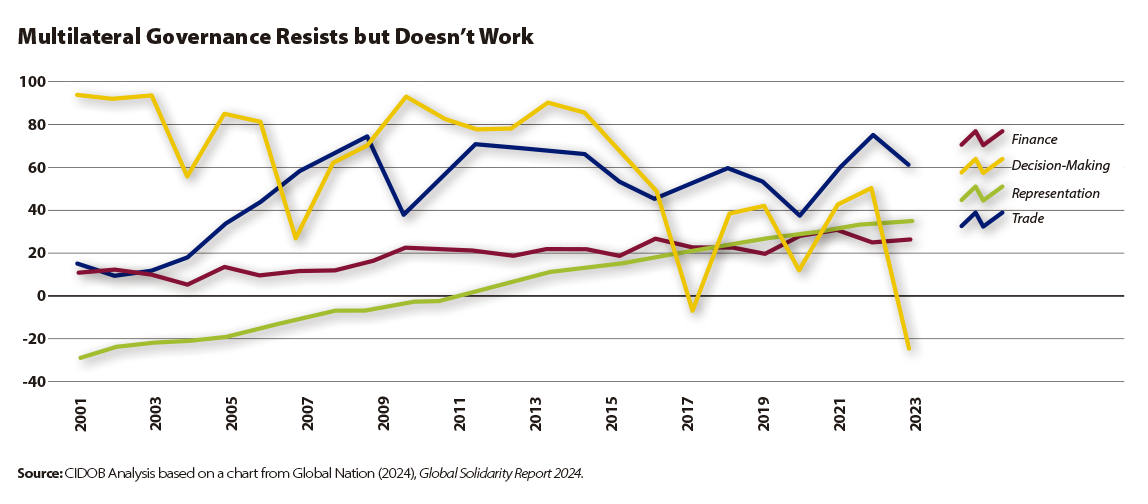

The year also starts with individualism on the rise. We live in a more emotional and less institutional world. If fear and anger have become what drive people when it comes to voting, this growing sense of despair is worryingly high among young people. In the 2024 European elections there was a decline in turnout among the under-25s. Only 36% of voters from this age group cast their ballot, a 6% decrease in turnout from the 2019 elections. Among the young people who failed to vote, 28% said the main reason was a lack of interest in politics (a greater percentage than the 20% among the adult population as a whole); 14% cited distrust in politics, and 10% felt their vote would not change anything. In addition, according to the Global Solidarity Report, Gen Z feel less like global citizens than previous generations, reversing a trend lasting several decades. This is true for both rich and poorer countries. The report also notes the perceived failure of the international institutions to deliver tangible positive impacts (such as reducing carbon emissions or conflict-related deaths). Disenchantment fuses with a profound crisis of solidarity. People from wealthy countries are “significantly less likely to support solidarity statements than those in less wealthy countries”, and this indifference is especially evident in relation to supporting whether international bodies should have the right to enforce possible solutions.

2-TRUCE WITHOUT PEACE

A year of global geopolitical turmoil ended with the surprise collapse of the Bashar Al-Assad regime in Syria; but also, with a three-way meeting between Donald Trump, Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Emmanuel Macron in Paris, against the backdrop of the reopening of Notre Dame. The rhythms of diplomacy and the quickening pace of war are out of step on international political agendas. And Russia, the common thread running through recent events in Syria and Ukraine, is quick to issue a reminder that any diplomatic moves must also go through Moscow. Given this backdrop, in 2025 we may speak of ceasefires, but not of peace.

For starters, the electoral announcements of a Trump intent on putting an end to the war in Ukraine “in 24 hours” prompted an escalation of hostilities on the ground with various actions: the appearance on the scene of North Korean soldiers in support of the Russian troops; authorisation for Ukraine to use US ATACMS missiles for attacks on Russian soil; and the temporary closure of some Western embassies in Kyiv for security reasons. Speculation about possible negotiations has increased the risk of a tactical escalation to reinforce positions before starting to discuss ceasefires and concessions.

While the diplomatic offensive may gain traction in 2025, it remains to be seen what the plan is, who will sit at the table and what real readiness the sides will have to strike an agreement. Ukraine is torn between war fatigue and the need for military support and security guarantees that the Trump administration may not deliver. Although, given the prospect of a capricious Trump, nor can we rule out the possible consequences for Vladimir Putin of failing to accept a negotiation put forward by the new US administration. Trump is determined to make his mark from the very start of his presidency, and that might also mean, in a fit of pique, maintaining the military commitment to reinforcing the Ukrainian army.

It is also an essential battle for Europe, which must strive to avoid being left out of negotiations on the immediate future of a state destined to be a member of the EU and where the continent’s security is currently at stake. The EU will have Poland’s Donald Tusk in charge of the 27 member states’ rotating presidency as of January, with the former Estonian prime minister, Kaja Kallas, making her debut as the head of European diplomacy. She is currently feeling the vertigo of Trump snatching the reins of a hasty peace while the member states have proved incapable of reaching an agreement on the various scenarios that might emerge in the immediate future.

In any case, the Middle East has already illustrated the frailty and limited credit of this strategy of a cessation of hostilities without sufficient capacity or consensus to seek lasting solutions. The ceasefire agreed in the war that Israel is waging against Hezbollah in Lebanon is more of a timeout in the fighting than a first step towards the resolution of the conflict. The bombings and attacks after the ceasefire are an indication of the fragility, if not emptiness, of a plan that neither side believes in. Meanwhile, the war in Gaza, where over 44,000 people have died, has entered its second year of devastation, transformed into the backdrop of this fight to reshape regional influence, but with a Donald Trump intent on pushing a ceasefire agreement and freeing hostages even before he takes office on January 20th.

The year begins with a change of goals in the region, but with no peace. While the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, made it clear that his priority now was to focus on Iran, the regional escalation unexpectedly hastened the end of the regime of Bashar al-Assad. With Russia bogged down in Ukraine, with Iran debilitated economically and strategically, and Hezbollah decimated by Israel’s attacks, the Syrian president was bereft of the external support that had propped up his decaying dictatorship. The civil war festering since the Arab revolts of 2011 has entered a new stage, which also changes the balance of power in the Middle East. We are entering a period of profound geopolitical rearrangement because for years Syria had been a proxy battleground for the United States’ relations with Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

We are therefore faced with scenarios that have been thrown wide open, where any negotiation proposal put forward will be more a strategic move than a prior step to addressing the root causes of the conflicts. And yet these diplomatic moves – individual and personalist initiatives primarily – will once again put to the test an international system plagued by ineffectiveness when it comes to delivering broad global consensus or serving as a platform to resolve disputes.

3- PROTECTIONISM AND AUSTERITY

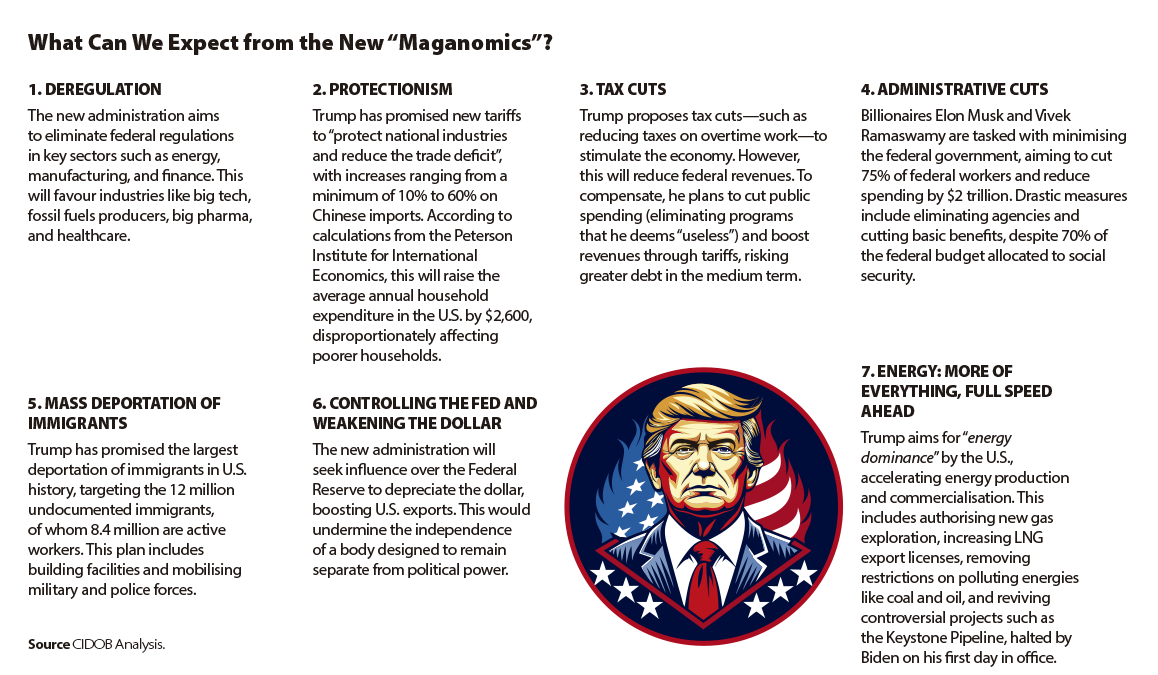

Donald Trump’s return to the US presidency steps up the challenge to the international order. If in his first term he decided to pull the United States out of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Paris climate agreement, now he is preceded by the announcement of a trade war in the making. The existing geo-economic fragmentation – in 2023 nearly 3,000 trade restricting measures were put in place, almost triple the number in 2019, according to the IMF – will now have to contend with an escalation of the spiral of protectionism should the new US administration keep its promise to raise tariffs to 60% on Chinese imports; 25% on goods coming from Canada and Mexico, if they fail to take drastic measures against fentanyl or the arrival of migrants at the US border; and between 10% and 20% on the rest of its partners. In 2025, the World Trade Organization (WTO) marks 30 years since its creation and it will do so with the threat of a trade war on the horizon, a reflection of the state of institutional crisis that is paralysing the arbiter of international trade.

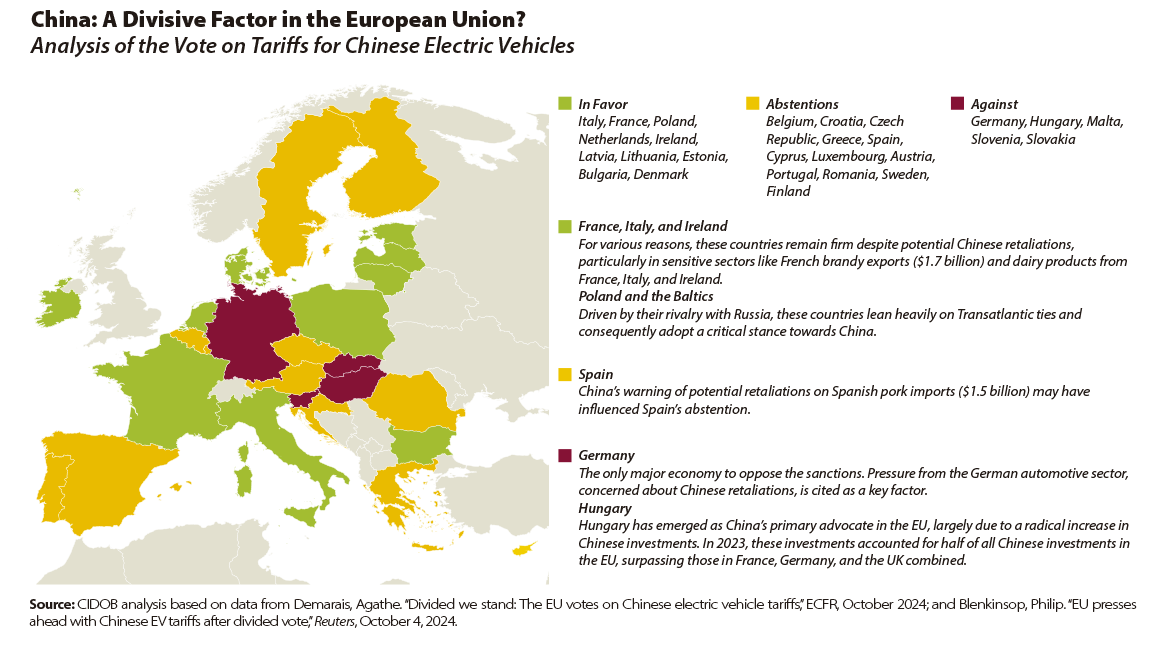

As a result, countries are looking to strengthen their positions through various alliances. The world is increasingly plurilateral. India is expanding its free trade agreements with the United Kingdom and in Latin America; in 2025 the EU must finally tackle a lengthy obstacle course to ratify the long negotiated deal with Mercosur. Trumpism, what’s more, reinforces this transactional approach: it fuels the possibility of more unpredictable partnerships and the need to adapt. Among those that have begun to reconsider goals and partners is the EU. The European countries will foreseeably make more purchases of liquefied natural gas and defence products from the United States to appease Trump. Despite US pressure and the profile of the new European Commission appearing to presage a harder line from Brussels on China in the economic sphere, nor can we rule out seeing fresh tension among the EU partners over the degree of flexibility of its de-risking strategy. A US withdrawal from the global commitments to fight climate change, for example, would intensify the need for alliances between Brussels and Beijing in this field. Likewise, it remains to be seen whether the emergence of European countries more accommodating of this geopolitical dependence on China may expose a new fault line between member states.

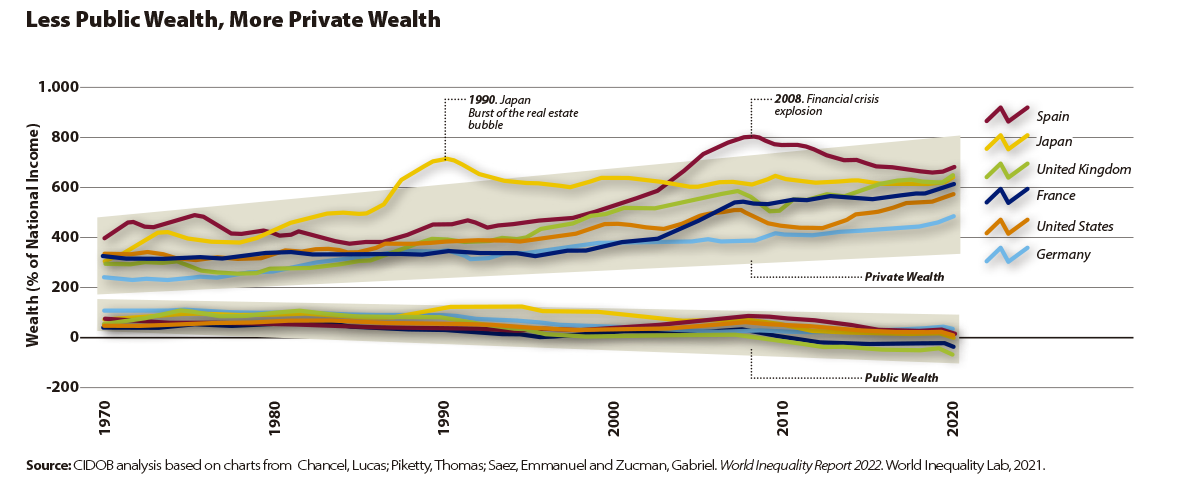

Given this uncertainty, recipes for fiscal discipline are also making a comeback. Brazil ended the year announcing cuts in public spending to the value of nearly $12bn; Argentina’s Javier Milei boasts of implementing “the world’s toughest austerity policy”; Mexico’s minister of finance and public credit, Rogelio Ramírez de la O, has vowed to reduce the fiscal deficit in 2025 by pursuing austerity in the public administration and cutting spending in Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos). In the United Kingdom, the prime minister, Labour’s Keir Starmer, has embraced the “harsh light of fiscal reality” in the budget and plans to raise some £40bn by increasing taxes and cutting spending in order to address the fiscal deficit.

The EU is also preparing to tackle US protectionism in the awareness of its own weakness, with the Franco-German axis failing and its economic model in question. Paris and Berlin are both in a moment of introspection, and the siren calls of austerity are once again ringing through some European capitals. In France, parliamentary division is impeding an agreement to avert a possible debt crisis, while in Germany it will be the next government – the one that emerges from the early elections of 23 February – that must address the stagnation of the economy and its lack of competitiveness.

Even though inflation is set to slip out of the picture somewhat in 2025, the effects of what Trump calls “Maganomics” remain to be seen. In the United States, the introduction of tariffs and the potential decline in the workforce in the wake of “mass deportations”, coupled with tax cuts, could increase inflation in the country and limit the Federal Reserve’s capacity to continue lowering interest rates. While Republican control of both houses in Congress and their majority in the Supreme Court may facilitate the adoption of these measures, actually carrying out the deportations appears to be much more difficult in view of the legal and logistical challenges it poses.

Meanwhile, despite the savings generated by a possible pared-back public administration and the income from tariffs, the independent organisation Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that Trump’s measures could increase the deficit significantly and place the debt on a path towards topping 140% of GDP in 10 years, from 99% at present. This means investors will be more demanding when it comes to buying US debt in the face of the risk of a fiscal crisis. It will also be crucial to see whether the attempts to undermine the independent regulatory agencies or the independence of the central bank are successful.

The IMF’s global growth forecast for 2025 is 3.2%, much the same as the estimate for 2024, but below the pre-pandemic trend. This figure, however, masks significant differences between regions, where the strength of the United States and certain emerging economies in Asia stands in contrast to the weakness of Europe and China, as well as the rapid pace of the change taking place globally from consumption of goods to consumption of services. In Asia, all eyes will be on the ailing Chinese economy, weighed down by its real estate sector, and how its leaders respond to the new restrictions on trade, investment and technology from the United States. At the close of 2024, the main Asian economies were going against the austerity measures expected in Europe and America. Both China and Japan have announced economic stimulus packages, although the desire to cut the 2025 budget on the part of the opposition in Seoul has triggered political chaos domestically.

In the circumstances, we can expect an increase in economic insecurity and an escalation of the fragmentation of the global economy, where we can already see like-minded nations moving closer together. Some key countries in the “reglobalisation” trend, like Vietnam or Mexico, which had acted as intermediaries by attracting Chinese imports and investments and increasing their exports to the United States, will see their model suffer in the face of pressure from the new US administration. The drop in interest rates worldwide, meanwhile, will allow some low-income countries renewed access to the financial markets, although around 15% of them are in debt distress and another 40% run the risk of going the same way.

4-GLOBAL DISMANTLING OF INSTITUTIONS

The brazenness of this world without rules is only increasing. The undermining of international commitments and security frameworks and growing impunity have been a constant feature of this yearly exercise on the part of CIDOB. In 2025, the crisis of multilateral cooperation may even reach a peak if personalism takes the lead and does even further damage to the consensual spaces of conflict resolution, i.e. the United Nations, the International Criminal Court (ICC) or the WTO. We live in a world that is already less cooperative and more defensive, but now the debate over the funding of this post-1945 institutional architecture may help to compound the structural weakness of multilateralism. The United States currently owes the United Nations $995m for the core budget and a further $862m for peacekeeping operations. Donald Trump’s return could lead to an even greater loss of funding for the organisation and prevent it from functioning properly.

It remains to be seen whether, despite the geopolitical rivalry, there are areas where agreement among powers is still possible. We remain in a world marked by inequality, heightened by the scars of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2020, the gap between the more and the least developed countries has been growing steadily. In 2023, 51% of the countries with a low human development index (HDI) had not recovered their pre-COVID-19 value, compared to 100% of those with a high HDI. Given these circumstances, it will be crucial to see the outcome of the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, which will take place in Seville in 2025.

In addition, 2024 ended with a bid from Brazil to seek an agreement in the G20 to levy the world’s wealthiest people with an annual tax of 2% on the total net worth of the super-rich, those with capital in excess of $1bn. But for the time being Lula de Silva’s proposal has gone no further than the debate stage. And while the United States is by far the country among the most industrialised nations where a much greater proportion of the wealth and national income ends up in the hands of the richest 1%, the arrival of the Donald Trump-Elon Musk entente in power in Washington will make it harder still to approve such a tax.

Likewise, in October 2024 Israel passed laws barring the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) from operating in the country and curtailing its activity in Gaza and the occupied territories of the West Bank by stopping contact between Israeli government actors and the agency. The legislation will come into force at the end of January 2025, exacerbating the humanitarian disaster in Gaza. Although most countries that paused their UNRWA funding have resumed contributions, the United States withdrew $230m. The mobilisation of the international community to ensure the survival of UNRWA once the Israeli law takes effect will be crucial to demonstrate the resilience of humanitarian action; alternatively, it may compound the collapse of another United Nations pillar.

Similarly, the dismantling of the institutions and rules of democracy has impacted spaces for protest in civil society, whether in the United States itself, in Georgia or in Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, political violence scourged Mexico, where as many as 30 candidates are thought to have been murdered in the runup to the presidential elections of 2024, and demonstrations were banned in Mozambique. The year 2024 was a tumultuous one globally, marked by violence in multiple regions: from the ongoing battle against al-Shabaab in East Africa and the escalating regional conflict in the Middle East to over 60,000 deaths in the war in Sudan to date. Global conflict levels have doubled since 2020, with a 22% increase in the last year alone.

The space for peace is shrinking. In 2025, the EU will end various training or peacebuilding missions in Mali, the Central Africa Republic or Kosovo, while the number of United Nations peacekeeping missions will also decrease in Africa. Similarly, if it is not renewed, the extended mandate of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) will end on August 31st. Some 10,000 blue helmets from 50 nations are deployed in the south of the country and they came under Israeli attack during the incursion against Hezbollah. All these moves reflect both the broad changes underway in the international security system and the crisis of legitimacy UN peacekeeping operations are suffering. Even so, the eighth peacekeeping Ministerial on the future of these operations and the five-year review of the international peacebuilding architecture will take place in May 2025, at a time when the organisation is trying to restore some of its relevance in countries gripped by violence like Haiti or Myanmar.

While political violence grows, international justice is faltering. Take the division in the international community caused by the ICC’s arrest warrants against the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and his former defence minister, Yoav Gallant, even among European countries that recognise the court. France refused to abide by the ruling, on the grounds of the supposed immunity of non-signatories of the Rome Statute, while Italy called it “unfeasible”. The response stands in stark contrast to the resolve of the European countries regarding the arrest warrants issued against Vladimir Putin or the leader of the military junta in Myanmar, Min Aung Hliang. The situation will not improve with Trump in the White House. While US opposition to the ICC has traditionally been bipartisan, the hard-line stance towards the court of the first Trump administration went much further than rhetorical censure, resulting in sanctions against the court itself and its officials, which the Biden administration subsequently lifted.

Which countries will best navigate this gradual dismantling of the international order? In 2025, we shall continue to see a highly mobilised Global South geopolitically, engaged in the reinforcement of an alternative institutionalisation, which is expanding and securing a voice and place for itself in the world, albeit with no consensus on a new reformed and revisionist order. In this framework, Brazil is preparing to preside another two strategic international forums in 2025: BRICS+ and COP30. As for Africa, the continent has become a laboratory for a multi-aligned world, with the arrival of actors such as India, the Gulf states or Turkey, which now compete with and complement more established powers like Russia and China. In late 2024, Chad and Senegal demanded the end of military cooperation with France, including the closure of military bases, in a bid to assert their sovereignty. South Africa, meanwhile, will host the G20, the first time an African nation will stage this summit on its soil, following the inclusion of the African Union (AU) into the group. It will mark the end of a four-year cycle in which the summit has been held in Global South countries. And in Asia there is the perception of some pacification processes underway: from the easing of tension on the border between China and India, with the withdrawal of troops in the Himalayas, to the return of trilateral summits among South Korea, Japan and China after a five-year hiatus. The region is withdrawing into itself in the face of the uncertainty that 2025 holds.

5- TECHNOLOGY CLASH AND (DE)REGULATORY PRESSURE

The tech competition between the United States and China is set to gather further pace in 2025. The final weeks of Joe Biden’s presidency have helped to cement the prospect of a clash between Beijing and Washington, which will mark the new political cycle. On December 2nd, 2024, the introduction of a third round of controls on exports to China, with the collaboration of US allies such as Japan and South Korea, further reduced the possibility of obtaining various types of equipment and software for making semiconductors. China, meanwhile, retaliated with a ban on exports of gallium, germanium and antimony, key components in the production of semiconductors, and tighter control over graphite, which is essential for lithium batteries.

Apart from this bipolar confrontation, in 2025 we shall see how tech protectionism gains currency worldwide. Global South countries have begun to impose tariffs on the Chinese tech industry, albeit for different reasons. While countries such as Mexico and Turkey use tariffs to try to force new Chinese investment in their territories – particularly in the field of electric vehicles (EVs) – others, like South Africa, are doing it to protect local manufacturers. Canada too announced a 100% duty on imports of Chinese EVs, following the example of the EU and the United States, despite having no EV maker of its own to protect.

Given the circumstances, for Xi Jinping 2025 will be a year to reassess the strategy that has enabled China to gain leadership of five of 13 emerging tech areas, according to Bloomberg: drones, solar panels, lithium batteries, graphene refining and high-speed rail. However, a decade on from the start of the Made in China 2025 plan – its road map towards self-sufficiency – development and innovation in the semiconductor sector in China has slowed, owing to its inability to secure more advanced chips, the machinery to produce them or more cutting-edge software.

Will the chip war escalate with Trump’s return to power? During the campaign, the president-elect accused Taiwan of “stealing the chip business” from the United States. Yet in 2025 the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (SMC) will start large-scale production of integrated circuits at its factory in the United States. The investment in Arizona by Taiwan’s biggest chip maker was announced by the first Trump administration, so it is not hard to imagine another round of investment in the future on the part of the new Republican administration to reinforce supply chain security.

In addition, Elon Musk’s influence in the White House also promises greater symbiosis between Silicon Valley and the Pentagon. Tech competition and the rise in conflicts across the world have restored Big Tech’s appetite for public contracts in the defence field, which means that with Trump’s return its leaders are hoping to gather the fruits of their investments in the presidential campaign. Just two days after the elections of November 2024, Amazon and two leading AI companies, Anthropic and Palantir, signed a partnership agreement to develop and supply the US intelligence and defence services with new AI applications and models. It seems likely, then, that the consensus reached in April 2024 between Biden and Xi Jinping to “develop AI technology in the military field in a prudent and responsible manner” will be rendered obsolete under the new Trump administration.

But hyper-technology extends beyond the military field, as it cuts across ever more sectors of the administration in ever more countries. The entry into force of the Pact on Migration and Asylum in Europe, for example, will be accompanied by new technological surveillance measures, from the deployment of drones and AI systems at the border in states such as Greece to the adaption of the Eurodac system – the EU database that registers asylum seekers – to gather migrants’ biometric data. This will only consolidate a model of surveillance and discrimination against this group.

It also remains to be seen what impact the new political majorities in the United States and the EU will have on tech governance. Following a flurry of regulation creation and legal action in the courts against the monopolistic power of the major tech firms, in 2025 we shall see a slowdown – if not a reduction – of new measures against Big Tech. The EU’s new political priorities, moreover, will put the emphasis in tech on security over competition, and we shall see the emergence of an internal debate on current regulation; over whether it can be implemented effectively or whether it has been too ambitious. It is a shift that contrasts with the regulatory trend, particularly regarding the use of AI, developing in the rest of the world, from South Korea to Latin America.

Lastly, the United Nations proclaimed 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ). Quantum computing is a branch of IT that will enable the development of more powerful computers that can run more complex algorithms, helping to make giant leaps in scientific research, healthcare, climate science, the energy sector or finance. Microsoft and another tech firm, Atom Computing, have announced they will begin marketing their first quantum computer in 2025. And Google has also unveiled Willow, a quantum chip that can perform a task in five minutes that it would take one of today’s fastest supercomputers quadrillions of years to complete. This new generation of supercomputers harnesses our knowledge of quantum mechanics – the branch of physics that studies atomic and subatomic particles – to overcome the limitations of traditional IT, allowing a host of simultaneous operations.

6-A “THIRD NUCLEAR AGE”?

While algorithmic complexity gathers pace, debates about nuclear safety take us back to the past, from a new rise of atomic energy to the constant recourse to the nuclear threat as a means of intimidation. With an increasingly weak global security architecture, the international arms race is hotting up without guardrails. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), both the number and type of nuclear weapons under development increased over the last year, as nuclear deterrence once again gains traction in the strategies of the nine states that store or have detonated nuclear devices. That is why the risk of an accident or miscalculation will still be very present in 2025, both in Ukraine and in Iran.

Indeed, coinciding with 1,000 days since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and an escalation of fighting on the ground, Vladimir Putin approved changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine, lowering the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons. The revised text states that an attack from a non-nuclear state, if backed by a nuclear power, will be treated as a joint assault on Russia. In order to drive home its message, the Kremlin threatened to use Russia’s Oreshnik hypersonic missile on Ukraine, capable of carrying six nuclear warheads and travelling ten times faster than the speed of sound. Against this backdrop, the deployment of North Korean soldiers to support Russia on the Ukrainian front in late 2024 also means the involvement of another nuclear power in the conflict and raises fresh questions about what Pyongyang will receive in return. Commenting on the subject, the NATO secretary general, Mark Rutte, said Russia was supporting the development of the weapons and nuclear capabilities of Kim Jong-Un’s regime. As a result, the threat of a potential upsetting of the balance in the Korean Peninsula and Trump’s return to power have further fuelled the nuclear debate in Seoul and Tokyo, which had already been reignited by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

There could also be changes in the United States’ nuclear policy. Project 2025, the ultraconservative blueprint that means to guide the Trump administration, champions the resumption of nuclear testing in the Nevada desert, even though detonating an underground nuclear bomb would violate the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which the United States signed in 1996. The nuclear arms industry already surged under the first Trump administration. This time, however, experts believe that if the programme is implemented, it would be the most dramatic build-up of nuclear weapons since the start of the first Reagan administration four decades ago.

At the same time, the two European nuclear states – France and the United Kingdom – are also in a process of nuclear modernisation. The British government has been immersed in an expansion of its arsenal of nuclear warheads since 2021 and, as a member of the AUKUS trilateral agreement along with the United States and Australia, in 2025 it will train hundreds of Australian officials in the management of nuclear reactors in order to prepare Canberra for its future acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines. France, too, is developing its own design for a “latest generation“ sub.

In addition, 2025 will be a decisive year for Iran’s nuclear programme. The deadline is approaching for the world’s powers to start the mechanism to reinstate all the sanctions lifted in the deal that put a brake on Iran’s nuclear expansion, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). So far, Tehran has already warned that if the sanctions return, Iran will withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The threat only adds to the risk of an escalation of hostilities in the Middle East and the possibility of Israel considering an attack on nuclear facilities in Iran.

Similarly, the nuclear debate has been revived in Europe, following a global trend. Nuclear energy production is expected to break world records in 2025, as more countries invest in reactors to drive the shift towards a global economy looking to move beyond coal and diversify its energy sources. The EU, which is at a critical juncture as it tries to satisfy the demand for energy while boosting economic growth, is also witnessing fresh impetus in the nuclear debate. Around a quarter of the EU’s energy is nuclear, and over half is produced in France. In all, there are more than 150 reactors in operation on EU soil. Last April, 11 EU countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden) signed a declaration that urged regulators to “fully unlock” the potential of nuclear energy and “enable financing conditions” to support the lifetime extension of existing nuclear reactors. Italy is mulling whether to cease to be the only G7 member without nuclear energy plants and lift the ban on the deployment of “new nuclear reactor technologies”. A possible return of the Christian Democrat CDU to the German chancellery, following the elections in February, could reopen the debate on the decision taken by Angela Merkel in 2023 to close the last nuclear reactor operating in the country.

Lastly, Taiwan, despite a strong aversion to nuclear in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in its neighbourhood, is also immersed in a process of reflection on nuclear energy, in a year in which the last operating plant is to close. Indeed, the need to meet the growing demand for semiconductors thanks to the AI boom, mentioned in the previous section, has put a huge strain on the country’s energy consumption. The Taiwanese government is not the only one in this situation. Microsoft is helping to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania, which closed in 2019, while Google (owned by Alphabet) and Amazon are investing in next-generation nuclear technology.

7- CLIMATE EMERGENCIES WITH NO COLLECTIVE LEADERSHIP

2024 will be hottest year on record. It will also be the first in which the average temperature exceeds 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, marking a further escalation of the climate crisis and the failure of attempts to keep the global temperature below that threshold. To June 2024 alone, extreme climate phenomena had already caused economic damage to a value of more than $41bn and impacted millions of people across the planet. And yet the global mitigation struggle is faced with a growing absence of political leadership. This was evident in the debates and outcomes of COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, in November, where every political effort was devoted to just one battle: finance. Even so, the pledge on the part of the wealthiest countries to provide $300bn a year by 2035 is considered insufficient to cover the needs of the poorest countries and ensure climate justice. The cost of mitigation and adaptation for developing countries is estimated at between $5tn and $6.8tn to 2030. The pessimism, moreover, is borne out by the facts: while in 2009 the developed countries made the pledge to devote $100bn a year to climate finance, they failed to meet that goal until 2022.

In Baku, in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory and the shadow of a political agenda that has relegated the climate to the back seat in the face of inflation or energy prices, the Global North chose not to fight the mitigation battle. If at COP28 in Dubai it was said for the first time that the world should embark on a transition beyond fossil fuels, at COP29 it was not even mentioned. The year 2025 will be one to measure commitments, both on finance and taking action. The signatories to the Paris Agreement (2015) must present their national action plans to demonstrate they are honouring the agreed mitigation commitments. The scheduled delivery date for this new round of national contributions is February, but it is looking like many countries will be late and that their level ambition will not match up to what the science and the climate emergency require.

In addition, the United States – the world’s second biggest greenhouse gas emitter after China – could deal a fresh blow to the global fight against climate change if Donald Trump again decides to withdraw his country from the Paris Agreement, in a repeat of his first term. He would find it harder, however, to leave the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the treaty that underpins the agreement and the multilateral talks on the climate. But this is not the only question mark over the United States’ “green transition”. Trump’s pick of Chris Wright, an oil executive from Liberty Energy and a climate crisis denier, to lead the Energy Department may again put fossil fuels before green energy goals.

The new European Commission must also decide what role it wants to play on the global climate stage. The new political majorities will make it difficult for the EU to act with one voice on climate matters, as demonstrated recently in the European Parliament with the controversial decision to postpone and dilute the European deforestation law. Thus in 2025 we will see growing tension in the EU to lower environmental regulations and standards.

While global progress in the mitigation battle slows and US leadership on climate matters fades, China is expanding its ambition and its influence. In 2025, hopes are pinned on China’s energy transition and its new role as voluntary financial contributor to the agreement sealed in Baku. According to the experts, China’s coal and CO2 emissions could peak in 2025 – five years ahead of its target. The climate progress China is making will have a clear impact not only on the planet, but also on the Asian giant’s economic and energy interests. Part of China’s economic transition since the pandemic has been directed at incentivising the development and introduction of renewables, making it the sector that most contributed to the country’s economic growth in 2023. But, at the same time, it also has geopolitical implications: the more its consumption of renewable energy grows, the less dependent it is on hydrocarbons imports from third countries, including Russia. According to the vice president, Ding Xuexiang, China has devoted $24.5bn to global climate finance since 2016. With greater pressure from Brussels for China to increase its contributions, we may see the Asian country trying to burnish its image through greater climate activism in 2025.

Still, the major players in renewables are the countries of the Global South. According to a study published by the think tank RMI, nations of the South are adopting these technologies at a much quicker pace and on a much greater scale than in the North. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that new solar and wind energy facilities in these countries have grown by 60% in 2024, with Brazil, Morocco and Vietnam at the head of the pack, reporting a greater adoption rate of these energies than part of Europe and the United States.

The staging of COP30 in 2025 in Brazil, one of the most ambitious countries in terms of climate commitments, raises even greater hopes and expectations of a new global impetus in the battle against climate change, one that takes account of the needs and demands of the Global South. While the adaptation discourse, a longstanding demand of these countries, is expected to begin to gain traction on the international and local agenda, the change of narrative could hide new challenges. For one, the need to think about a world beyond the 1.5°C temperature increase. And for another, the risk of compounding inequalities between communities and countries with greater adaptation capacity, since poverty is directly linked to a country’s resilience to climate risks and its capacity to recover from them. This places developing countries in a situation of considerable risk, and the adaptation gap is getting wider.

8- GENDER: THE END OF CONSENSUS

In 2025, polarisation around gender consensus will increase. As conservative agendas gain political ground, the international agreements that for decades have enabled gender equality to advance are under challenge again. On the one hand, 2025 will be a year of celebration of two international milestones for women’s rights: the 30th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted at the Fourth World Conference on Women (1995), and the 25th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS). Celebrating the two agreements, adopted at a time marked by optimism and the successes of transnational feminist movements, will be an invitation to reflect on lost consensuses, present challenges and the lack of political will to secure their full adoption and implementation. On the other hand, the Generation Equality forum, launched in 2021 to mark 20 years since Resolution 1325 with the aim of consolidating progress on women’s and girls’ rights in five years, will have to account for its unfulfilled commitments. According to the Population Matters association, one in three countries has made no progress on gender matters since 2015, and the situation of women has worsened in 18 countries, particularly Afghanistan and Venezuela.

The difficulty in achieving new consensuses, leaderships and political will is apparent in the bid to adopt new international plans to protect the rights of women and girls. According to WILPF figures, 30% of the National Action Plans (NAPs) for domestic implementation of the WPS agenda expired more than two years ago, and the national strategies of 32 countries or regional organisations will end between 2024 and 2025, raising a question mark about their updating and renewal in an international context marked by tension and disputes, the rise of the far right and polarisation around gender.

Two agreements to promote gender equality will end in 2025 and must be renegotiated: the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Gender Equality Strategy and the EU’s Gender Action Plan III (GAP III). In the latter case, it is hard to envisage a European Commission as committed to gender equality as it was during Ursula von der Leyen’s first term. During that time, the German marked several gender equality milestones, like the Directive on combatting violence against women or EU accession to the Istanbul Convention. The first steps of her second term, however, have offered a glimpse of the difficulties she will encounter to continue down that path. While in her presentation of the political guidelines for the new commission, von der Leyen declared her commitment to gender equality and the LGBTIQ collective, the team of commissioners proposed by the member states has already challenged her desire for parity in the commission she leads. Just 11 of the 27 commissioners are women – including the president herself and the high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, Estonia’s Kaja Kallas. In addition, and as the name of the post indicates, the figure of commissioner for crisis management and equality – a competence first introduced in 2019 – will also be responsible for the management and prevention of crises now, diluting the emphasis on gender parity. Similarly, with a European Parliament that has shifted right and with a greater number of EU governments led by far right and antifeminist groups, it will be difficult to make headway on progressive measures.

Against this backdrop, Donald Trump’s return to the presidency of the United States augurs another severe setback for gender equality, particularly in the field of sexual and reproductive health rights. The arrival in power of Republican candidates is always accompanied by the restoration of the Mexico City policy (also known as the global gag rule), which places severe international restrictions on sexual and reproductive health rights. It is a policy that bars NGOs in the health sector from offering legal and safe abortion services or even actively promoting the reform of laws against voluntary termination of pregnancy in their own countries if they receive US funding – even if they do so with their own funds. Yet this restriction is not limited to the field of development assistance. Among other measures included in Project 2025, there is the elimination of language for gender equality, sexual orientation and gender identity, or the protection of sexual and reproductive health rights in future United Nations resolutions, but also in domestic policy and regulations of the United States.

In 2017, countries such as Sweden and Canada – at the time the only ones to have adopted a feminist foreign policy – were quick to fill the void left by the change of US priorities, with the introduction of international projects like SheDecides, which sought to channel international political support to safeguard women’s “bodily autonomy” throughout the world. Since 2022, however, with Sweden ditching the feminist flag in foreign policy and other countries such as Canada, France or Germany focusing on their upcoming elections and the domestic political instability they must face in 2025, it is hard to imagine alternative leaderships and funding. Europe is experiencing its own regression.

But the reversals in political consensus at the highest level do not stop there. Following the US elections, harassment and misogynist texts have been sweeping social media with messages such as “your body, my choice”, which has registered an increase of up to 4,600% on X (formerly known as Twitter). Cyberviolence against women is on the rise. According to a 2023 study, around 98% of deep fakes are pornographic and target women. These scandals have multiplied with AI, opening a debate on the regulation and possible criminalisation of such cases.

9- MIGRANT DEPORTATIONS AND RIGHTS

As 2024 comes to an end, thousands of Syrian refugees are returning home. After 14 years of civil war, the fall of Bashar al-Assad has raised hopes in a country facing the world’s largest forced displacement crisis, according to the United Nations, with over 7.2 million internally displaced people – more than two-thirds of the population – and 6.2 million refugees, mainly living in the neighbouring countries of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. Yet despite the uncertainty of the political moment and that fact that fighting is still taking place on the ground, some EU countries (Germany, Italy, Sweden, Denmark, Finland or Belgium) are rushing to suspend the asylum applications of Syrian refugees as others, like Greece and Austria, are taking measures to expel them. The Austrian government has even launched a deportation programme that is reassessing the situation of some 40,000 Syrians who had been granted refugee status in the country over the last five years. All these moves further aggravate the debate among European partners over the concept of “safe third country” so criticised by social organisations.

2025 will be a year of deportations, in terms of discourse and in practice. Immigration has been the cornerstone of Donald Trump’s political career, and in his second presidential campaign he vowed to carry out the biggest deportation in history. How will it be done? It remains to be seen if we will see staged deportations or what the real impact might be on the US labour market of a policy that, according to multiple studies, is not a zero sum game in favour of US-born workers. Irregular migrants work in different occupations to those born in the United States; they create demand for goods and services; and they contribute to the country’s long-term fiscal health. There are also doubts about the economic sustainability of this type of policy, particularly in view of the prospect of a growth in flows and the dramatic increase in the number of deportations in the United States already since the pandemic (some 300,000 people a year). Yet Trump’s victory saw the value of firms engaged in the deportation of migrants and monitoring or supervising the border, as well as the management of detention centres, rocket on the stock market. The deportation business is booming.

And deportation is not only an instrument of the Global North. Iran is considering mass deportations of Afghans; the Turkish deportation system has been bolstered by hundreds of millions of euros from the EU; and Tunisia too is conducting illegal “collective expulsions” of immigrants with funds from the EU. Egypt, meanwhile, for months has been carrying out mass arrests and forced returns of Sudanese refugees.

On a European level, in 2025 the EU member states must present their national plans to implement the new Pact on Migration and Asylum. The rules are scheduled to enter into force in 2026, but Spain has asked for the use of new tools for border control and the distribution of migrants to be brought forward to next summer. The pact, however, has already been challenged by some member states, which are calling for it to be replaced by a model that allows migrants to be transferred to detention centres located outside the EU in countries that are deemd to be safe. Italy’s decision last August to open centres of this type in Albania, though it ended in a resounding legal defeat for Georgia Meloni’s government, offered a clear foretaste of the growing tension between policy and the rule of law. In these circumstances, moreover, in 2025 judges may become more acutely aware of the lack of tools to safeguard the rights to asylum and refugee status in a global environment that has been dismantling international protection for years. The war in Gaza – which in its first year caused the forced displacement of 85% of the population – illustrates the calamitous failure of international law, both in the humanitarian field and regarding asylum.

Fear, as a dynamic that permeates policy both in the migration field and in international relations, will gain ground in 2025. That is why the staging of deportations has become a symbolic deterrent. The criminalisation of migrants – who feel targeted – and the social burden narrative that certain governments exploit with an agenda of public cuts, are setting the tone in an international system increasingly obsessed with border protection and lacking the interest (or tools) to ensure safe and regular migration.

10- MILITARISATION OF INSECURITY

In this world of fragile institutions, the cracks through which organised crime can seep and expand are growing. Organised crime networks are multimillion dollar, transnational businesses that construct hierarchies and strategic alliances. As the international order fragments, mob geopolitics is evolving with new actors and a change of methodology: rather than compete, organised crime groups are cooperating more and more, sharing global supply chains for the trafficking of drugs and people, environmental crimes, counterfeit medicine or illegal mining – which in some countries, like Peru or Colombia, are as profitable as drug-trafficking, if not more so. Global networks that stretch from China to the United States and from Colombia to Australia, thanks to “narco submarines”, account for the diversification of businesses and locations, but they also explain their capacity to penetrate the structures of power and undermine the rule of law, because they exist in a context of increasing corruption of states and their legal and security systems.

In Ecuador, for example, a hotspot of drug-trafficking on a global scale, the government has declared war on 22 criminal organisations and speaks of an “internal armed conflict”. Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti, today is a city in the grip of rival criminal groups locked in turf wars, which have led to the various armed gangs seizing control of neighbourhoods, police stations and even temporarily blocking the airport. The latest escalation of violence has left nearly 4,000 dead and over 700,000 displaced people inside the country, according to the UN Human Rights Office. Meanwhile, the geopolitical crisis of fentanyl, where the epicentre is Mexico as a well-established producer of this synthetic drug since the COVID-19 pandemic, has developed into a bilateral problem of the first order with the United States and Canada and a threat to Central America.

In Europe too, port cities like Marseille, Rotterdam or Antwerp are major points of drug entry and seizure. Organised crime is currently the biggest threat facing the Swedish government, with 195 shootings and 72 bombings that have claimed 30 lives this last year alone. Globalisation means this new hyperconnected reality has even reached the islands of the Pacific, which now occupy a prominent place on the international strategic chessboard thanks to a proliferation of trade, diplomatic and security commitments. It has also transformed the region’s criminal landscape, with the presence of Asian triads and crime syndicates, the cartels of Central and South America, and criminal gangs from Australia and New Zealand.

According to the Global Organised Crime Index, at least 83% of the world’s population lives in countries with high levels of crime, when in 2021 it was 79%. If organised crime is one of the winners in this new fragmented order, the rise in violence has also brought the imposition of policies of securitisation. In Latin America, for instance, the clear choice to militarise security – seeking national solutions (containing the violence) to what is a transnational challenge – has favoured “firm hand” responses.

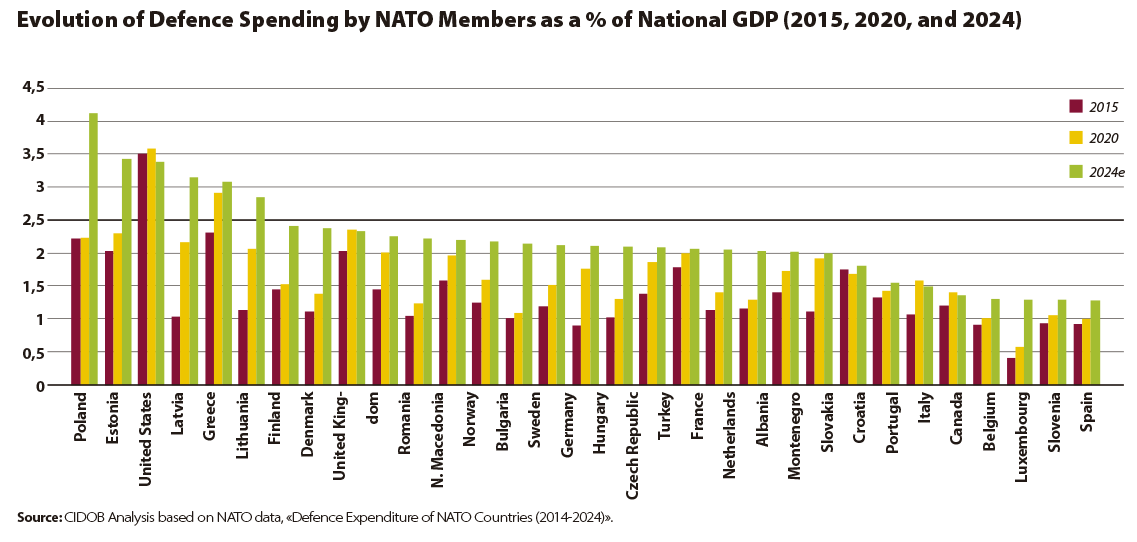

The world is rearming. With the rise in conflicts, like the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, so revenues from sales of arms and military services have grown. According to the SIPRI, 2025 will the biggest year for military spending in a long time. Given these circumstances, the pressure on NATO countries to increase their defence spending will ramp up again with the return of Donald Trump to the White House, but also on account of the unpredictability of the international environment. Over the coming months, NATO must negotiate various internal fractures: for one, the demand to raise defence spending to 3.5% of GDP; for another, the differences among allies over the strategies used against Russia. Countries such as Poland and the Baltic nations are calling for a more aggressive stance against Moscow, while other members, such as Hungary or Turkey, are looking to maintain a more neutral approach. This could hinder the formulation of a unified strategy in the face of threats from Russia and future geopolitical scenarios in Ukraine. In addition, during his campaign Trump questioned the commitment to mutual defence enshrined in Article 5 of the NATO treaty. If the new US administration adopts a more isolationist stance, the European allies might doubt US reliability as a pillar of their security. There is also growing concern in the EU over the security of essential components and undersea cable infrastructures, which are critical to connectivity and the global economy, particularly in the wake of several episodes of suspected sabotage like those seen in the Baltic Sea in the last few months.

Lastly, China’s growing militarisation of its maritime periphery is also triggering fresh security fears in Asia. Beijing is promoting – ever more zealously – a Sinocentric view of the Indo-Pacific region. This is raising fears that 2025 will see an increase in the aggressiveness of China’s strategy to turn East Asia into its exclusive sphere of influence.

Against this backdrop, the quickening pace of geopolitics raises multiple questions both for analysts and for international relations actors themselves. The world is struggling with the posturing of new leaderships, shifting landscapes that are redefining long-running conflicts and a Sino-US rivalry that may develop into a trade and tech war in the near future. Given this prospect, the multi-alignment efforts that many countries across the world are trying to make, with security at heart, are becoming increasingly complex as confrontation escalates among the major global powers .

CIDOB calendar 2025: 80 dates to mark in the diary

January 1 – Changeover in the United Nations Security Council. Denmark, Greece, Pakistan, Panama and Somalia, which were elected in 2024, will join the council as non-permanent members, replacing Ecuador, Japan, Malta, Mozambique and Switzerland. Meanwhile Algeria, Guyana, Sierra Leone, Slovenia and South Korea, which were elected in 2023, will start their second year as members.

January 1 – Poland takes over the six-month rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union. The government of Donald Tusk will focus council activity on moving forward with the accession processes of the countries aspiring to join the EU, comprehensive support for Ukraine and strengthening transatlantic ties with the United States. The latter priority must accommodate an uncomfortable truth for Brussels: the return of Donald Trump to the White House.

January 1 – Bulgaria and Romania become full members of the Schengen area. In November 2024, Austria lifted its veto on the full integration of Bulgaria and Romania into the Schengen area. The two countries, members of the EU since 2007, were admitted to the borderless travel zone in March 2024, but checks on people were only lifted at ports and airports. Now the same will apply to land border checks, and the common visa policy will be in operation at the EU’s external borders.

January 1 – Finland takes up the yearly rotating chairmanship of the OSCE. The organisation responsible for maintaining security, peace and democracy in a hemisphere comprising 57 countries across Europe, Asia and North America has been through some low times since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, which, despite the condemnation, remains a member. The 32nd OSCE Ministerial Council meeting will take place in Finland between November and December 2025. The Russian foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, who was barred from the council meeting in 2022, did however attend in 2023 and 2024.

January 1 – Handover between the African Union’s ATMIS and AUSSOM missions in Somalia. The AU will remain involved in the efforts to bring peace to Somalia and stabilise the country – stricken by the al-Qaeda allegiant organisation al-Shabaab – with a new mission, the third consecutive operation since 2007. However, AUSSOM will come up against escalating tension between the governments of Somalia and Ethiopia, after Addis Ababa struck a deal on naval access to the Gulf of Aden with the secessionist Republic of Somaliland.

January 1 – 30th anniversary of the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO enters its third decade of activity in an international context marked by growing opposition to globalisation, the rise of protectionism worldwide, and Donald Trump's electoral promise to impose a 60% tariff on Chinese goods and 10-20% on other imports.

January 7 – John Mahama is sworn in as president in Ghana. In the English-speaking West African country, which has one of the most robust democratic systems on the continent, John Mahama, former president of the Republic for the first time in 2012-2017 and candidate of the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) party, will return to power. Mahama will take over from the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) president Nana Akufo-Addo, who defeated him in 2016 and 2020.

January 15 – Daniel Chapo takes office as president of Mozambique. The fifth straight president from the leftist FRELIMO party since national independence in 1975 was declared the winner of the elections of October 9, 2024. His opponents claimed fraud and called for popular protests. The crackdown left over 30 dead, including children. While rich in natural resources, Mozambique remains mired in underdevelopment and faces jihadist threats and serious climate risks.

January 20 – Donald Trump takes office as president of the United States. The Republican starts a second non-consecutive term after roundly defeating the Democrat Kamala Harris in the election of November 5, 2024, with promises to deport undocumented immigrants, cut taxes and levy new trade tariffs. Trump returns to the White House with a more radical nationalist rhetoric than the one that marked his first term between 2017 and 2021.

January 20-24 – Annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (Davos forum). The influential group of thinkers each year convenes figures from politics, business, academia and civil society to a select and extremely high-profile international gathering in the Swiss town of Davos. In 2025, it will put three major global challenges up for discussion: geopolitical shocks, stimulating growth to improve living standards and stewarding a just and inclusive energy transition.

January 26 – Presidential elections in Belarus. Unlike in 2020, the dictator Alexander Lukashenko will not even have to pretend there is a competition at the ballot boxes because the country’s election commission will only allow token candidates to stand, and none from the gagged opposition. The longest-serving president in Europe – in power since 1994 – and staunch ally of Vladimir Putin is sure to win a seventh presidential term.

January 31 – End of the mandate of EUCAP Sahel Mali. A regional instrument of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), the European Union Capacity Building Mission in Mali was launched in 2015 to assist the government in the fight against organised crime. Its continuation remains in doubt after the EUTM training mission, geared towards the fight against jihadism, was not renewed in 2024 and following the anti-French turn taken by the military junta in Bamako. Its twin operation in Niger, EUCAP Sahel Niger, also ended in 2024. On September 19, the EUTM in the Central African Republic will likewise come to a end.

February 9 – General elections in Ecuador. The centrist Daniel Noboa won the snap presidential election in 2023, called by his predecessor, the liberal conservative Guillermo Lasso, to avoid impeachment by the country’s congress. Noboa will seek re-election, this time for a normal constitutional period of four years, in a climate overshadowed by the brutal wave of criminal violence afflicting Ecuador. His chief rival once again will be Luisa González, a protege of leftist former President Rafael Correa.

February 10 and 11 – Artificial Intelligence Action Summit, France. The French government is staging one of many international AI-related events in 2025. Unlike the rest, this action summit will gather heads of state and government and leaders of international organisations, as well as company CEOs, experts, academics, artists and NGOs. Following on from the summits of 2023 in Bletchley, in the United Kingdom, and 2024 in Seoul, the Paris meeting will look at how AI can benefit public policy.

February 11-13 – 13th World Governments Summit, Dubai. The WGS is a Dubai-based organisation that each year gathers leaders from government, academia and the private sector to debate technological innovation, global challenges and future trends in pursuit of good governance. The theme of the 2025 edition is “Shaping future governments”.

February 14-16 – 61st Munich Security Conference. Held every year since 1963, the MSC is recognised as the most important independent forum for the exchange of opinions on international security. In 2025, over 450 policymakers and high-level officials will discuss, among other topics, the EU’s role in security and defence, the security implications of climate change and new visions of the global order.

February 15 and 16 – 38th African Union Summit, Addis Ababa. The AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government will hold an ordinary session in which Mauritania will hand over the one-year chairpersonship, and the successor to the Chadian Moussa Faki as chairperson of the African Union Commission will be elected. The Pan-African organisation has been running the NEPAD development programme since 2001 and in 2015 it adopted its Agenda 2063 to hasten the continent’s transformation. Six member states – Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Sudan – are currently suspended following their respective military coups.

February 23 – Federal elections in Germany. Six days after Chancellor Olaf Scholz fired his finance minister Christian Lindner, of the liberal party FDP, from the government over budget differences, on November 12, 2024, the Social Democrat came to an agreement with the Christian Democrat opposition to bring forward by seven months elections due in September. The SPD and The Greens, the only remaining partner following the collapse of the “traffic light” coalition, go into the vote languishing in the polls, with the CDU/CSU and the far-right AfD in the lead.

March 1 – Yamandú Orsi takes office as president of Uruguay. The candidate from the leftist opposition Broad Front beat the conservative Álvaro Delgado, from the ruling National Party, in the runoff presidential election of November 24, 2024. The successor to the outgoing president, Luis Lacalle, has a five-year term. Broad Front’s return, after holding power for the first time between 2005 and 2020, will precede the celebration of the bicentenary of Uruguay’s Declaration of Independence on August 25.

March 1 - End of the mandate of the new Transitional Government in Syria. This was the date announced on December 10, 2024, two days after the fall of the Baathist regime of Bashar al-Assad in the lightning offensive launched on November 27 against Damascus by a coalition of rebel groups, by the new Prime Minister, Muhammad al-Bashir. The day before, he was appointed to the post by the main rebel wing, the Islamist guerrilla group HTS (Hayat Tahrir al Sham) of Abu Muhammad al-Jolani and the Syrian Salvation Government, which Bashir himself had been leading.

March 3-6 – 19th edition of the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona. A fresh yearly edition of the world’s leading mobile communication technologies event, where device manufacturers, service providers, wireless carriers, engineers and scientists unveil the latest developments in the sector. The 2025 MWC, the theme of which is “Converge. Connect. Create”, will focus on topics including the next phase of 5G, IoT devices and generative AI.

First quarter – Sixth European Political Community Summit, Albania. The EPC came about in 2022 at the initiative of Emmanuel Macron. It is a biennial gathering of the leaders of 44 European countries that seeks to provide a platform to discuss strategic matters in a non-structured framework of dialogue among the 27 EU member states and a further 17 states from the continent that are candidates for accession or are associated with the EU.

First quarter – Election of the president of Armenia by the National Assembly. The term of Vahagn Khachaturyan will come to a close no later than April 9. This is the date the tenure of the previous holder of the post, Armen Sarkissian, was due to end. Sarkissian resigned in 2022. A parliamentary republic, Armenia remains in Russia’s orbit, a situation that is proving increasingly problematic for the authorities in Yerevan given Moscow’s lack of action towards the country’s military defence in the face of attacks by Azerbaijan. One of these attacks in 2023 forced the surrender of the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh in the Armenian enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh.

First quarter – First European Union-United Kingdom Summit. The Labour government of Keir Starmer champions a new era of bilateral relations between London and Brussels. Following Brexit in 2020, the United Kingdom’s economic exchange with the 27 EU members takes place under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), which provides a limited area of free trade in goods and services. The British prime minister is pursuing “constructive” ties with the EU that cover complex issues such as immigration, although he rules out a return to the free of movement of workers, the customs union and, in short, the single market.

April 13-October 13 – Universal exhibition, Osaka. The Japanese city is organising a world’s fair for the third time, after 1970 and 1990. The theme of Expo 2025 is “Designing future society for our lives”.

May 6 – 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the European Union and the People's Republic of China. Beijing and Brussels will celebrate half a century of diplomatic relations at a time defined by tensions over China's overcapacity, the imposition of tariffs on Chinese Electric Vehicles, and China's role in the war in Ukraine.

May 9 – 75th anniversary of the Schuman Declaration. In 1950, the French foreign minister, Robert Schuman, made a proposal to place France and Germany’s coal and steel production under a single authority. This was the genesis of a web of supranational integration institutions (ECSC, EEC, Euratom) that decades later would result in what today is the European Union.

May 12 – General elections in the Philippines. The deterioration of the relationship between the Marcos and Duterte families, who lead the current ruling coalition, could trigger a competition between the two main governing parties in an election where more than 18,000 positions in the Senate, the House of Representatives, and provincial and local governments across the archipelago are up for renewal.

May 19-23 – 29th World Gas Conference, Beijing. The growing importance of natural gas as an alternative fuel to petroleum products in the transition to carbon neutrality, its status as a raw material in the production of grey hydrogen and the greater demand for gas as a result of the war in Ukraine gives the triennial WGC gathering particular importance. The International Gas Union (IGU) has been staging the event since 1931. In China, production, imports and consumption of gas are increasing constantly.

May 26 – End of Luis Almagro’s tenure as OAS secretary general. Uruguay’s Luis Almagro was elected head of the OAS in 2015, and in 2020 he secured re-election for a second and final five-year term. The candidates to succeed him are the Paraguayan foreign minister, Rubén Ramírez, and his counterpart from Suriname, Albert Ramdin. The vote will take place at the General Assembly, which in June will hold its 55th regular session in Antigua and Barbuda.

May – Presidential elections in Poland. The Civic Platform (PO), a pro-European and liberal conservative party, returned to power in Poland in 2023 led by Donald Tusk. It is hoping to win this direct ballot and bid farewell to an uncomfortable cohabitation with the head of state elected in 2015 and re-elected in 2020, Andrzej Duda, from the right-wing party Law and Justice (PiS). The Polish system of government is a mixed one, where the president wields important powers.

May – Pope’s visit to Turkey. The Vatican is planning this papal visit, of a marked ecumenical nature, to commemorate 1,700 years since the First Council of Nicaea, whose doctrinal legacy is accepted by all the Christian churches. Pope Francis already made an apostolic visit to Turkey in 2014.