The world in 2023: ten issues that will shape the international agenda

Text finalised on December 15, 2022. This Nota Internacional is the product of collective reflection by CIDOB’s research team in collaboration with EsadeGeo. Coordinated and edited by Carme Colomina, it includes contributions from Inés Arco, Anna Ayuso, Jordi Bacaria, Ana Ballesteros, Paula Barceló, Pol Bargués, Moussa Bourekba, Victor Burguete, Anna Busquets, Carmen Claudín, Anna Estrada, Francesc Fàbregues, Oriol Farrés, Agustí Fernández de Losada, Marta Galceran, Matteo Garavoglia, Blanca Garcés, Patricia García-Durán, Seán Golden, Berta Güell, Josep Mª Lloveras, Ricardo Martínez, Esther Masclans, Óscar Mateos, Sergio Maydeu, Pol Morillas, Viviane Ogou, Francesco Pasetti, Cristina Sala, Héctor Sánchez, Ángel Saz, Reinhard Schweitzer, Antoni Segura, Cristina Serrano, Eduard Soler i Lecha, Marie Vandendriessche, Alexandra Vidal and Pere Vilanova, while the work of other CIDOB members was vital to its preparation.

Limits, both individual and collective, will be tested in 2023, whether it be inflation, food security, the energy crisis, rising pressure on global supply chains and geopolitical competition, international security and governance systems breaking down, and the collective capacity to respond to it all.

The impacts of this permacrisis contribute directly to worsening household living conditions, which translate into rising social unrest and citizen protests, which will only increase. Cracks are widening and deepening – geopolitical, social and in the access to basic goods.

The war in Ukraine has made it clear that the more risks are associated with a geostrategic confrontation, the more obsolete the collective security frameworks built to deal with them appear. The mismatch between means, challenges and deterrence instruments worsens.

In 2023, limits, both individual and collective, will be tested, whether it be inflation, food security, the energy crisis, rising pressure on global supply chains and geopolitical competition, international security and governance systems breaking down, and the collective capacity to respond to it all. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the unexpected scenario of 2022 that became decisive because it accelerated the erosion of the post-1945 order. However, the true scope and depth of the war’s global impact is only starting to become clear. We face not only a crisis of enormous dimensions, but a new process of structural change whose end remains unknowable.

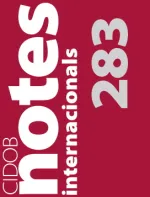

Like the white ball on a pool table, the war in Ukraine has given new momentum to various transformations and crises that were already underway, which then began colliding with each other, increasing the sense of global disorder and acceleration, of geopolitical uncertainty, and of social upheaval. Where will the balls triggered by the war in Ukraine stop? What level of disorder will prevail when they do? Of all the many crises, which could be the black ball that drops into the pocket too soon and produces a new existential threat? Above all, as continuous vulnerability and uncertainty become the new normal, what collective responses are being built?

Like a Venn diagram, all these war-accelerated changes overlap and intertwine, some driven by necessity, others by new geopolitical logics. We face conflicts that intersect, and transitions that seemed to be working hand in hand to build a more sustainable world now momentarily colliding. That is why in 2023 the permacrisis – word of the year 2022 – ranges from Western powers’ strategic disorientation to the vulnerability many of the world’s people feel due to the rising prices of basic products and the inability to protect common goods like food, energy and the climate. Fragility is pervasive, from collective security to individual survival.

It remains to be seen if 2023 will be the year of escalation – intentional or accidental – or the time to cement small de-escalations that reduce geopolitical tensions and their economic impact. But 2022 has shown us that the greater the risks, the more obsolete are the regulatory frameworks and protection systems that should protect us against so much volatility

1. Strategic competition accelerates

The war in Ukraine has accelerated the schism and confrontation between the major global powers. Arms have become another point of tension in US–China relations, joining trade, technological, economic and geostrategic competition. This will only be accentuated in 2023. But the world before us is not divided into two watertight blocs. Rather, a full-scale reconfiguration of alliances is underway, which forces all other actors to reposition themselves in relation to the new strategic competition dynamics and to seek out their own spaces in a transformation that is global, but whose epicentre in 2023 will remain in Europe.

Rivalry is no longer a taboo concept – it is seen as the new state of relations between the great powers. However, many governments would rather not choose sides in this China–US bipolarity and prefer to maintain fluid relations in different aspects of the liberal international order in order to take advantage of the opportunities that emerge from the great power competition, according to their national interests. So, 2023 will also be the year of the others – when we will more clearly see an acceleration in other powers’ strategic competition to gain prominence while keeping spaces for cooperation open with the United States, as well as with China and Russia. It will be a year to pay attention to the strategies of India and Turkey, the evolution of Saudi Arabia, and the changes that may emerge from Lula da Silva's Brazil and Latin America’s most recent electoral cycle – where China has consolidated its weight and influence, easily winning the international contest.

In 2023, India will chair both the G20 and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). That places Narendra Modi at the head of two alliances with divergent objectives, and his foreign policy is expected to be assertive in a pre-election year, as 2024 will see him attempt to renew his third mandate. The international sanctions on Russia over the war in Ukraine have helped make Modi a grateful importer of Russian oil, but the Indian prime minister had no qualms about reprimanding Vladimir Putin for invading his neighbouring country at the SCO’s Samarkand summit. He also allowed himself to be courted by Western powers seeking new spaces of influence in the Indo-Pacific.

2023 will be a complicated electoral year for Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Turkey – the clearest example of a regional power that is both a NATO member and close to Russia, with whom it hopes to play a mediating role in the Ukrainian conflict. Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, has been engaged in a profound rethink of its foreign policy for some time. In 2023 two different paths open up: on the one hand, speculation mounts that, following the normalisation of relations between Riyadh and Tel Aviv, the next step may be for the Gulf state to consider signing the Abraham Accords. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia’s rapprochement with the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) – which plan to discuss the group’s possible expansion to include new members at their next summit in South Africa – would strengthen the Saudi kingdom’s presence in the Global South. At the moment, Iran, Argentina and Algeria are among those applying to join the BRICS, and count on Russia’s support. Last year Iran also applied for membership of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and it should be approved in April 2023.

Amid this geostrategic upheaval among the others, one dilemma that will weigh especially heavily on the European Union (EU) is whether it is willing to fill the void if the US reduces its support for Ukraine. Over the coming months, China and the United States will begin to question the costs, duration and level of support they are prepared to continue giving this war. The Biden administration is well aware that the new Republican majority in the House of Representatives and a certain weariness in American public opinion are beginning to seed doubts about the continuity of the level of aid the US has given the government in Kiev so far. China’s ability to act abroad, meanwhile, will also depend on maintaining stability at home, which was disrupted at the end of 2022 by protests against Xi Jinping's zero-COVID policy. Despite the “unlimited friendship” that Beijing and Moscow declared at the beginning of 2022 and the “mutual support for the protection of their core interests, state sovereignty and territorial integrity”, the foundations of the alliance between China and Russia will above all be defined by Beijing’s strategic interests.

Beyond these new alliances, energy crises are also accelerating geopolitical changes. The stance of the international community on Iran and Venezuela – both oil and gas producers – could change. Turkey, France and even the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have said that the sanctions on both regimes should be reviewed in order to alleviate the crisis in the energy market. And, at the end of November 2022, the United States lifted some energy sector sanctions to Venezuela in response to Nicolás Maduro's gesture of resuming talks with the opposition. At least that was the reason given – because the move also served to bring another player into the energy market. Iran, meanwhile, heads in the opposite direction. The desire to try once again to finalise a nuclear agreement has given way to confrontation, and diplomatic channels have been frozen since the regime began repressing civil protests and, above all, due to the sale of drones to Russia.

This ramping up of strategic competition has also reached new spaces and frontiers, of which we are only now beginning to be aware, via the struggle over physically non-existent dimensions, like the digital world, and barely reachable ones, like outer space and satellites. Russia's scheduled departure from the International Space Station in 2024 marks the end of cooperative space relations, with the parallel construction of a Russian space station transferring the fragmentation of the global order into space. This is neither a new nor an isolated event, but a speeding up of discreet movements that began years ago, and which led Moscow to open up new avenues for space collaboration in, for example, Latin America. In 2021, Russia concluded a space cooperation agreement with Mexico, which joined the Global Navigation Satellite System (or GLONASS, the Russian acronym for this version of the US GPS or European Galileo), already installed in Nicaragua since 2017. China, for its part, has also spent almost a decade building its Espacio Lejano Station in Argentina, raising suspicions in the United States about its dual use for civil and military purposes.

2. Inefficient global collective security frameworks

The war in Ukraine has shown that the more risks a geostrategic confrontation involves, the more obsolete the collective security frameworks appear. Since February 24th 2022, global and European security architecture paradigms have changed dramatically. On the one hand, NATO’s role has been revitalised. On the other, the images of the Russian military invasion strengthened the perception of an international security system that is breaking down and increased the feelings of vulnerability and strategic disorientation kindled by the structural changes underway.

Nuclear disarmament is in reverse. The permanent members of the UN Security Council – China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States – continue to expand and modernise their nuclear arsenals and appear to be elevating their importance in their military strategies. Meanwhile, technological advances – now a decisive factor and field of confrontation – continue to lack an international framework to regulate geopolitical relations in cyberspace.

Likewise, Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine has also lifted the taboo on making nuclear threats, even if they remain rhetorical for now. In turn, a new debate has begun on the concept of deterrence. The shrinking of nuclear arsenals that characterised the post-Cold War period has come to an abrupt end and we are entering a new decade of rearmament. China has embarked on a major nuclear expansion, including, according to SIPRI’s Yearbook, building over 300 new missile silos. The same Swedish research institute also estimates that North Korea has assembled up to 20 warheads, but probably has enough fissile material enough for building 45 to 55 nuclear devices. While the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says that Iran is planning a massive expansion of its uranium enrichment capacity.

The mismatch between deterrence instruments, means and challenges thus worsens. The West has sought refuge in its old security frameworks, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has revitalised the transatlantic connection. The return of war, in its classic form, to the edge of NATO’s eastern flank and Russia becoming a security threat once again have accelerated the strengthening of both the allies’ military muscle – with increased arms investments and deployment on the ground – and its political weight – via the adhesion of Sweden and Finland in 2023, pending the approval of Hungary and Turkey. But with global geostrategic balances in flux, NATO's internal contradictions will remain vulnerable to the strategic disorientation.

Looking beyond transatlantic frameworks, the inert state of collective security instruments has regional impacts that vary according to the conflict in question, and include new power vacuums, deepening instability and violence, or the strengthening of a minilateralism that seeks to assemble alternative shared security spaces to face geostrategic challenges.

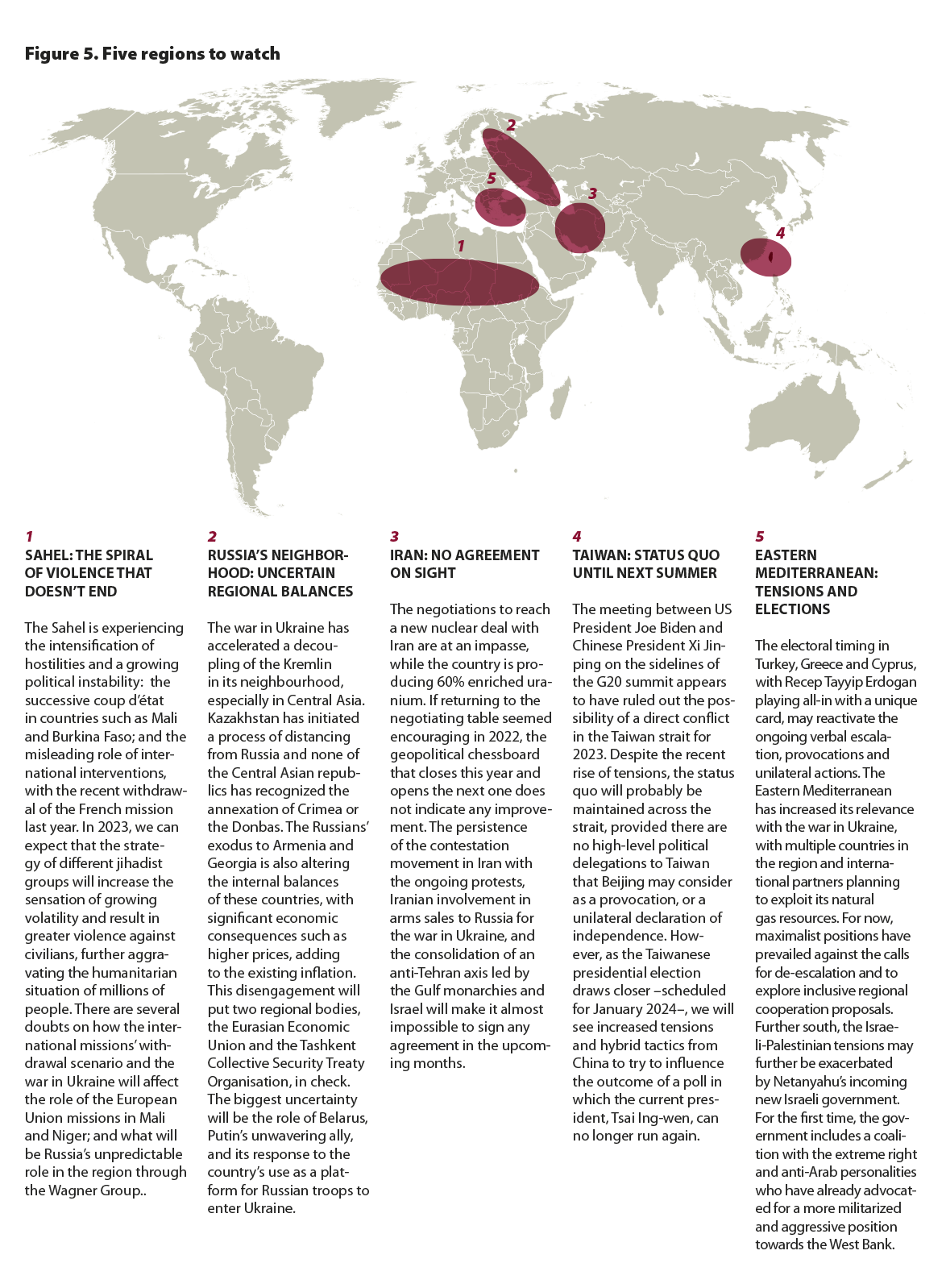

The political instability and violence plaguing the Sahel exemplifies this failure of regional security frameworks as well as the changing hegemonies in the Global South. In recent years, the region has experienced successive coups in countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, as well as the spread of jihadism towards the Gulf of Guinea. All of this is added to the humanitarian and security effects of a profound climate crisis. The end of Operation Barkhane announced by Emmanuel Macron in November 2022, and the consolidation on the ground of the Wagner Group – the Russian private security company with close ties to the Kremlin – mean the region faces profound change in the deployment of international forces. On the one hand, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is rethinking its future after troop withdrawals were announced by the United Kingdom, Germany, Côte d'Ivoire (in 2022), Benin and Sweden (by the end of 2023). On the other, the Russia–Africa summit scheduled for February could herald a rise in collaboration agreements with Moscow, which is presenting itself as a security ally and grain supplier in the midst of a food crisis.

The level of instability in the Sahel is a collective failure for France, for regional powers like Nigeria, and for multilateral peacekeeping initiatives, especially the United Nations.

Just as they do in the Sahel, multiple actors seek to exploit regional leadership gaps in other crisis settings to take the opportunity to advance their national interests. The various frozen conflicts – which tend not to involve peace agreements, but a cessation of hostilities based on a de facto status quo – could be thaw at any time and create new hotspots in 2023. The danger is particularly stark in Russia’s neighbourhood and other areas under the Kremlin’s influence. Some embers already began to glow in 2022.

Last summer, hostilities resurfaced between Armenia and Azerbaijan, leading old players like the EU – eyeing Azerbaijan’s natural gas – to show renewed interest in the region, taking advantage of the void left by Russia to open up new spaces for cooperation. In September, several days of clashes between Kyrgyz and Tajik border guards left hundreds dead and caused rising tensions, with both countries accusing the other of amassing forces at the border.

Likewise, in the Indo-Pacific, where the systemic competition between China and the United States is especially pronounced, minilateral agreements have emerged that focus on shared security interests and go beyond the merely geographical considerations typical of such groupings in the past. In some cases, minilateralism is seen as a potential answer to the ineffectiveness of today’s multilateral platforms, which remain hostage to the geostrategic competition between great powers. In 2022, cooperation was stepped up on the Quadriteral Security Dialogue (known as the Quad), – the alliance between the US, Japan, India and Australia –, although the first year of the AUKUS – the acronym use to designate the pact between Australia, the UK and the US – brought very limited progress. 2023 will show whether this trend is consolidated and minilateral initiatives continue to expand – South Korea joining the “Quad Plus” would be one sign of this. We will also see how far other emerging initiatives hasten the erosion of the existing cornerstones of multilateral and regional cooperation.

The weakening of multilateralism and of the spaces meant to govern global challenges not only affects collective security frameworks, but also the mechanisms of promoting and guaranteeing peace. The United Nations’ glaring absence from the war in Ukraine and the inoperability of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) are two examples. Rethinking global security also means equipping ourselves with instruments of peace, and Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has deepened this failure. 2023 will be the year to consider how this war ends – even if the military situation on the Ukrainian front and the political situation in Russia appear uncongenial to negotiations. The more time passes, the worse it will get for Vladimir Putin, given the redistribution of political power underway within the Kremlin – something it is very tricky to elucidate from the outside. But the foundations of Putinism are cracking.

Negotiations on Ukraine will need frameworks and instruments that work. The existing spaces – the Minsk agreements and OSCE mediation – have so far failed. In this context, European divisions over the future of the EU's relationship with Russia are likely to re-surface with greater force in 2023. Meanwhile, the establishment of a frozen, chronic conflict in eastern Ukraine cannot be ruled out – as the EU’s High Representative, Josep Borrell, has recognised.

Therefore, 2023 may not be the year we see new peace structures emerge, but it is high time to start thinking about how to create them.

3. Transitions collide

The green and the digital transitions, which seemed to work hand in hand towards building a more sustainable world, have collided. The war in Ukraine and the impact of the sanctions on Russia have altered markets, dependencies, climate commitments and even the expected timeframes for the transition to alternative energies. So, has the effect of this crisis accelerated or sabotaged the energy transition?

In October 2022, the International Energy Agency declared that the war in Ukraine was a turning point for policy change and energy markets “not just for the time being, but for decades to come”. In the short term, however, the fear of supply shortages during the winter has boosted the demand for coal. Current market and economic trends suggest that global coal consumption increased by 0.7% in 2022 and will rise in 2023 to an all-time high. The building of new fossil-fuel infrastructure in Europe and China, the delays to coal-fired power plant closures, the reopening of already-closed plants, and the extension of the limits on their operating hours mean that in spite of indices of changing trends, the climate ambitions needed to reverse the current course are being undermined, and we remain on track for temperature rises of 2.5ºC by 2100, according to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Nuclear energy is also being strengthened – with new plants being built in France and the United Kingdom, and Germany and Belgium postponing reactor closures until 2023 and 2032, respectively. In 2023 the controversial addition of gas and nuclear to the EU’s green energies taxonomy will enter into force.

The fear of a winter of supply shortages and energy crises for industry and households has accelerated the deepening of the EU's single energy market. Europe has agreed to increase purchases of liquefied natural gas (by 70%, according to Bruegel), to reduce demand for natural gas, and has made new gas purchase agreements with countries like Norway, Azerbaijan and Algeria. In 2023, more robust efforts will be needed to handle the uncertainty of a future without Russian gas, which supplied 17.2% of the EU's natural gas imports in September 2022 and enabled large consumers like Germany to guarantee their reserves. In China, the demand for imports of liquefied natural gas and other energy sources may be reactivated as its zero-COVID policy comes to an end.

Once the winter passes, the world will have to look for new energy providers beyond Russia. The resulting new global competition will keep prices up. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Europe may face a shortfall of 30 bcm (billions of cubic meters) in its gas reserves in summer 2023. As Africa emerges as a coveted region for multiple stakeholders who seek to invest in its energy sector – especially producer countries like Algeria, Nigeria and Tanzania – the interest in developing cleaner alternatives on the continent could be derailed. In 2023 it will be important to assess the EU’s willingness to stick to its ambitions for a transition that is just towards Africa, with the beginning of the implementation of the “EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package” presented in early 2022.

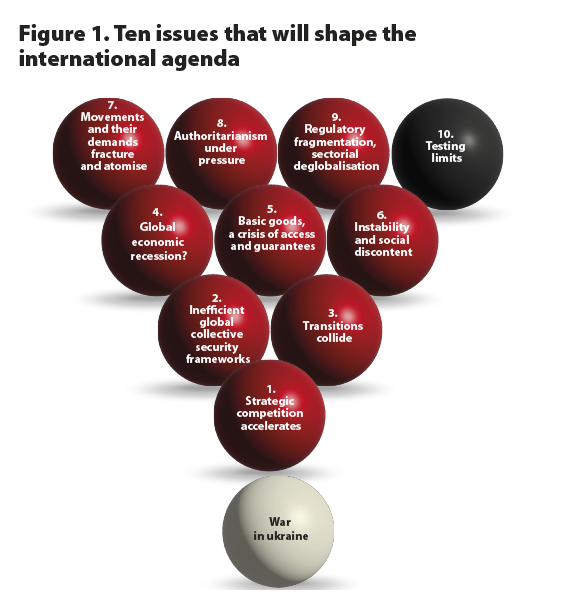

The other great bet in the energy diversification race is the higher use of renewable energies – with solar the main alternative thanks to its price and relatively quick construction and installation. For the time being, the US midterm results have saved the Inflation Reduction Act, which proposes to invest $369 billion in energy security and fighting climate change over the next decade. Asia’s large economies are also seeking to raise their clean energy targets (China, India and South Korea) and to quickly complete a green transition (Japan’s Green Transformation programme). In Europe, the REPowerEU plan and the EU Solar Energy Strategy aim to raise solar energy output to 320 gigawatts by 2025. However, to achieve these objectives, Europe is increasingly looking towards China – imports of solar panels produced in China have increased by 121% since the start of 2022, according to InfoLink, a Taiwanese consultancy specialised in renewables. In this transition, the competition over rare earths will take centre stage and in 2023 the EU will present its Critical Raw Materials Act. The EU aims to avoid a new dependence on China, which accounts for 60% of the global production of these minerals and the components need to make solar panels, as well as the electric batteries and technological components that are essential to the “twin transitions” of climate and technology.

Some studies warn that a very specific number of elements that are vital for the green and digital revolution – and much scarcer in concentrated purity than the well-known lithium, cobalt, silicon and tungsten – could start becoming scarce as early as 2025. Although renewable energies continue to be more affordable than fossil fuels, market tensions due to inflation, supply chain disruption and rising rare earths and metals prices led the cost of building wind farms to rise by 7%, solar panels to double and batteries for storing energy to rise by 8% in 2022, and they may continue rising globally next year.

This is where the collision between the two transitions accelerates. Digitalisation is seen as an essential condition for advancing decarbonisation and the development of new circular economy models. Its benefits are clear: according to the World Economic Forum, digital technologies could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 15%. New technologies – like 5G, the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence – have been presented as instruments for improving energy and material efficiency, reducing energy consumption and predicting and monitoring the weather in order to develop better policies for handling the climate emergency. And yet, as digitalisation – and the technological transformation it implies – accelerates and spreads, so does its impact on the environment and climate change.

The internet is responsible for 3.8% of global CO2 emissions and 7% of electricity consumption. In fact, the figure is much higher if we include the extraction of metals and rare earths needed for its hardware, transporting those materials, and the impact of e-waste. The trends towards using new technologies like cryptocurrencies, the cloud, artificial intelligence, the metaverse and the Internet of Things will mean energy demand continues to grow.

In tandem, producing the physical infrastructure of the digital entails highly polluting extraction processes. The short service life of some of these products and the need to renew and update equipment due to technological innovations also means more electronic waste, of which only 17.3% is recycled. Over 80% ends up in landfills or in nature, contaminating land and groundwater and affecting food and water systems, especially in developing countries.

It is the countries of the Global South that are disadvantaged by the digital divide, as well as by a lack of investment and access to green technologies. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report published in April 2022 explicitly mentioned this tension: “Digital technologies have significant potential to contribute to decarbonisation … Yet, if left unmanaged, the digital transformation will probably increase energy demand, exacerbate inequities and the concentration of power, leaving developing economies with less access to digital technologies behind”. Africa’s climate finance shortfall is $2.8 trillion and Southeast Asia’s is $3.1 trillion, according to the Asian Development Bank.

4. Global economic recession?

The war in Ukraine’s effects on energy, the persistent disruptions to the global supply chain, and the monetary policies adopted to handle rising inflation have led to pessimism about the economic future of 2023. According to the International Monetary Fund, global economic growth at the end of 2022 will be around 3.2%. However, in the forecasts for next year the figure falls to 2.7% – the lowest since 2001, with the exception of pandemic-hit 2020. The European Central Bank warns that the eurozone could soon enter a slight technical recession or stagnation. This is a bleak scenario for a world still trying to reverse the social and economic ravages of the pandemic as it faces volatility once again.

Inflation – which we listed as a key trigger of destabilisation last year – has continued to rise. The causes are multiple, including supply bottlenecks, increased energy costs and fiscal stimulus. Economists disagree about their relative impact and, as a result, about the most appropriate remedy.

The IMF estimates that inflation will peak in 2022, with an annual global average of 8.8%, falling to 6.5% in 2023 and 4.1% in 2024. However, while the World Bank warns that current policies may not be enough to reduce inflation, other experts warn of the danger of an overreaction that could aggravate the effects of this price rise. The ECB's monetary measures to curb inflation will continue over the coming months and the US Federal Reserve, for its part, is expected to continue raising interest rates in 2023.

In some parts of the planet, the economic, monetary and social risks are likely to make 2023 highly combustible. In the Middle East, inflation has reached all-time highs, with Lebanon, Turkey and Iran registering price rises of 162%, 85% (the highest since June 1998) and 41%, respectively, making access to food even more difficult for a significant part of the population. Syria and Yemen have also seen the price of the basic basket rise by around 97% and 81%, respectively.

With presidential elections scheduled for June 2023, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is under fire for policies that have hurt the Turkish lira, fuelling a currency crisis in the country. The lira’s fall by 44% in 2021 and 29% in 2022 has been the main driver of inflation, along with higher energy prices.

The Argentine peso has also lost 41% of its value against the dollar on the informal and financial markets, and 2022 will end with prices up by around 97%, while forecasts for 2023 suggest a 95.9% rise (compared to the 60% projected by the government in the national budget). Latin America’s third-largest economy has suffered high inflation for years, aggravated since March by the effects of the war in Ukraine. Argentina made a commitment to the IMF to achieve fiscal balance in 2024, a goal that seems increasingly distant, and the high public debt weighs heavily on the country's economy and the presidential elections scheduled for October 2023.

The risk is rising of a debt crisis spreading through emerging economies in 2023. Sri Lanka was the first alarm. In May 2022, the country declared itself unable to pay interest on its international debt for the first time, announcing that it lacked the dollars to import basic products. In 2023, El Salvador’s progress will also be worth following. In 2022, the government has implemented an inconsistent monetary policy, marked by a trade deficit, scant reserves and, after ushering bitcoin into the economy, was affected by the cryptocurrency’s collapse in November. The Central American country must repay $800 million at the beginning of 2023, but for now Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele has chosen to buy back the country’s own debt before it matures.

According to The Economist, 53 emerging countries are on the brink of being unable to meet their debt payments due to rising prices and the global economic slowdown. Among the countries in a particularly delicate situation in 2023 will be Pakistan, Egypt and Lebanon, which will struggle to meet foreign debt payments. It will also be interesting to see the economic policies of Latin America’s new left-wing governments, and whether they are forced to respect austerity policies that put their promises of social improvement at risk or, on the contrary, whether they increase public spending.

The European Union must begin negotiating the necessary adjustments to the Stability and Growth Pact in 2023. At the start of November, the European Commission presented a reform proposal that reduces fiscal rigidity in order to comply with the restrictions on debt (60% of GDP) and deficit (3% of GDP), which were suspended at the start of the pandemic. The Commission offers country-specific adjustment paths, rather than a one-size-fits-all. In exchange, countries will face sanctions if they do not comply with the established rules. Reforming the economic governance framework will require the approval of the 27 and it remains to be seen how the traditional defenders of fiscal discipline, like Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Finland, will react.

The economic turmoil has also reached the large global technology corporations. In November 2022, Meta, Twitter and customer management platform Salesforce laid off 24,000 people in the United States alone, while Amazon launched the largest workforce cuts in company history, in absolute terms, affecting about 10,000 workers. In China, tech giants like Baidu, Didi and Alibaba have laid off around 20% of their workforce, depending on the sector. And in November Tencent also announced that it would lay off 7,000 workers.

Strengthened by the digital acceleration experienced during the pandemic and their dominant market positions, the technology giants have been exposed to a double stress test, which will force them to evaluate the sustainability of their business model. On the one hand, large digital corporations must deal with high interest rates and the changes to consumption patterns caused by the rising cost of living. On the other, questions surround their future due to the dependence on rare earths that are already causing resource conflicts.

Throw in Elon Musk’s abrupt landing at Twitter and his first clash with the European Union and its plans to limit the monopoly power of these large platforms and strengthen content moderation policy, and we see how these giants’ transnational power has met a new desire for regulation. The legislative package on digital services and markets (the DSA and the DMA) approved by the EU in 2022 will enter into force on January 1st 2024, at the latest

5. Basic goods, a crisis of access and guarantees

The war in Ukraine has worsened existing issues with the access to energy, food and drinking water. The provision of global public goods, a prerequisite for development and vital for reducing poverty and inequality between countries, is currently suffering the ravages of geopolitical rivalry, a new confrontation over natural resources and the effects of weakened global governance and international cooperation.

The impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on global exports of agricultural products, seeds and fertilisers has aggravated the food crisis already produced by the convergence of climatic shocks, conflicts and economic pressures. After years of progress, these interconnected factors have led the number of people suffering from extreme hunger to break the worst records. The world faces an unprecedented food crisis with no end in sight. According to the United Nations, in 2022 some 345 million people in 82 countries live in a situation of acute or high-risk food insecurity, around 200 million more than before the pandemic.

In the Middle East and North Africa, a region already battered by inflation and which imports over 50% of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine, the rising cost of living and the shortage of basic goods have triggered mass protests. The World Food Programme (WFP) warns that 2023 could be even worse. This year's food crisis was down mainly to the logistical interruption produced by the blockade of cereal and fertiliser exports, but in 2023 food supply could be endangered by the effects of these disruptions on crops, as well as the possibility of extreme weather events. Food shortages even affect international humanitarian aid organisations, whose resources for dealing with rising famine figures are dwindling.

In Ukraine, at least 15.7 million people require urgent humanitarian protection and 6 million lack water supply. In Afghanistan, 8 million are at risk of famine. A very severe drought in southern Ethiopia, added to the political crisis that has seen armed clashes between the central government and the Tigray People's Liberation Front, has already displaced 4 million people, while 2 million are in danger of suffering famine. Emergency situations are also occurring in South Sudan and Yemen.

The violation of a basic right such as access to food also directly affects other human rights, such as those to health, water and to an adequate standard of living free from violence. These interlinked crises, provoked and exacerbated by war, have a devastating impact on women and girls around the world. The United Nations has condemned the alarming rises in gender violence and transactional sex for food and survival that further endanger women’s physical and mental health.

High energy prices will also play a part in declining global development indices. Around 75 million people who recently gained access to electricity are likely to lose their ability to pay for it, meaning that, for the first time since the International Energy Agency began reporting data, the total number of people in the world without access to electricity has risen, and almost 100 million people may once again depend on firewood for cooking, instead of cleaner and healthier solutions.

Developing countries are experiencing blackouts and protests due to the energy crisis and the impossibility of obtaining energy at affordable prices. In Indonesia over 400 demonstrations have taken place over the price of petrol in 2022, while in Ecuador there were more than 1,000 protests in the month of June alone over fuel prices. Meanwhile, oil and gas producing countries like Qatar are growing ever richer.

At the European level, the winter of 2023 will be a time to test the limits of the solidarity between EU countries. While multiple joint measures have been negotiated to alleviate economic pressures on markets and households (from joint gas purchases to the long-term overhaul of the European electricity market to favour renewable energy in EU energy production, including a voluntary reduction of 10% of gross electricity consumption), these measures clash with the national fiscal responses of certain member states and have caused internal friction between governments because they once again show the unequal capacity of European countries. Germany, for example, has allocated funds of close to 8% of its GDP (€264 billion in 2021) – around double the combined fiscal measures of the next two largest spenders in absolute terms: France (€71.6 billion) and Italy (€62.2 billion).

2023 will mark the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and 30 years since the adoption of the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action on Human Rights. In this context, the UN continues to insist on the need for renewed consensus on global public goods, including universal vaccination – the most compelling example of the prevailing inequality in the access to basic goods. According to Oxfam, around 5.6 million people die every year due to a lack of access to health services in regions with fewer resources.

COVID-19 vaccination processes laid bare inequalities, particularly in Africa and the eastern Mediterranean, that will continue to be problematic in 2023, especially in the most indebted countries of both the Global North and South. The goal of vaccinating 70% of the world’s population World Health Organization (WHO) by the end of 2022 will not be met in much of Africa, but neither will it in some countries in Europe, Latin America and Oceania.

The US government, meanwhile, has admitted that in early 2023 it will run out of funds to buy and distribute COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, meaning that they will no longer be subsidised by the administration. The projections also indicate that the reserves of booster doses purchased so far will run out at the beginning of the year. This suggests that the fight against the pandemic will fall to the private market in a country where 41% of adults say they struggle to pay medical bills, which obliges them to go into debt.

6. Instability and social discontent

The permacrisis directly impacts worsening household living conditions, which translates into increased social unrest and public protests as expressions of discontent. In 2022, demonstrations have been recorded in over 90 countries due to problems accessing public goods.

In Latin America, high fuel prices sparked protests in Peru, Ecuador and Panama over the course of the year, as well as Argentina, where protesters demanded jobs and assistance to deal with high inflation rates. This social unrest will undoubtedly impact the build-up to elections in Ecuador and Argentina, which are scheduled for February and October 2023, respectively.

The winter of discontent in Europe – which has already seen thousands of citizens take to the streets in Greece, the United Kingdom, Austria, Germany and the Czech Republic – could intensify in 2023, when the consequences of the energy crisis will be more visible. The EUpinions survey reveals that 49% of the EU population give the higher cost of living as their main concern. Meanwhile, the economic sacrifices to meet the energy crisis have slightly reduced support for European Union energy independence at any cost: support was 74% in March, but in September – before the cold – it was 67%. With prices more likely to remain high than disappear, 2023 will bring more protests.

The Middle East could once again be the epicentre of a new wave of mass protests after the democratic progress that began a decade ago ended and Tunisia returned to authoritarianism. With inflation approaching 2011 levels, when social unrest and frustration triggered the start of the Arab Spring, Lebanon, Tunisia, Egypt and Algeria could once again see protests against the current regimes. Iran is another country to follow. The repression of the protests that began after the death of the young Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini has so far killed 488, at least 44 of them were children, as well as seeing thousands arrested. The resilience shown, especially by the young people who mobilised throughout the country, will keep the protests alive in 2023, with greater mobilisation a real possibility if other grievances are added in, such as the country's delicate economic situation, international and regional tensions, and Iran's attacks on the Kurdish region of Iraq.

The spontaneous and unprecedented protests against China’s zero-COVID policy – ignited by a fire in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang region – opened a peephole into the frustration prevalent among large swathes of the population that may re-emerge at any time. In Thailand, the results of the elections scheduled for 2023, in which Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha will seek re-election after serving the maximum eight years in office since the 2014 coup, could once again provoke mass pro-democracy protests.

With the pandemic all but forgotten, demonstrations demanding social, climate and gender justice will also return to the streets. The announcement that COP28 will be held in the United Arab Emirates went down like a lead balloon among climate activists already disgruntled by the evasive “phase out” of fossil fuels and coal agreed at the last two meetings. Holding such a major summit in an oil and gas-producing country seems to mean climate hope must be deferred to COP29, which could be held in Australia, along with the Pacific Islands. But the climate movement will take to the streets again in 2023. Extinction Rebellion has already called for over 100,000 activists to surround the UK parliament in early April 2023, given the anticipated difficulties of mobilising civil society at the UAE COP.

Demonstrations to support sexual and reproductive rights will also be notable, as the US midterms showed, where the right to abortion was a major factor in electoral participation. The overturning of Roe v. Wade last June, which guaranteed women’s right to abortion in the United States, will lead over half the states to ban abortion or restrict the grounds for accessing it. As these measures are adopted in 2023, activists for sexual and reproductive rights will take to the streets and actions will be launched to halt some of the restrictions or improve access to contraceptives at state level.

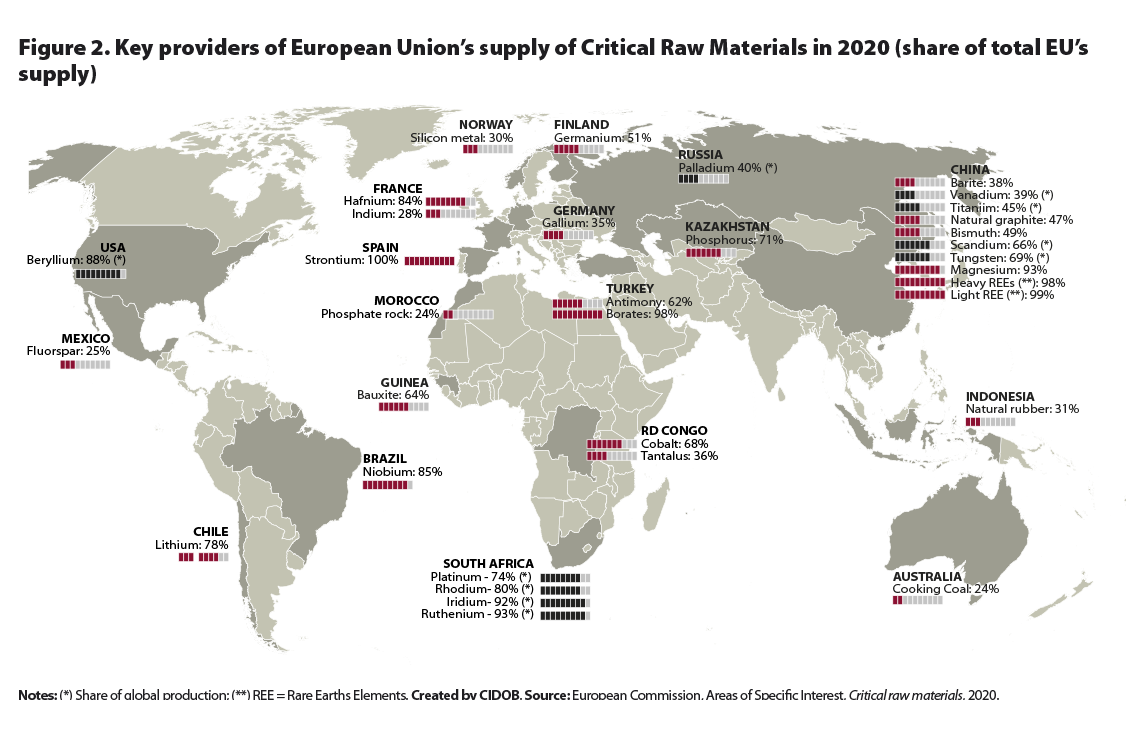

But, will all these protests be heard? According to Harvard's Mass Mobilization Project, non-violent protests have grown in recent years around the world, but few have been effective enough to bring about change. According to the study, only 42.4% of protests over the last decade have achieved their demands. In 2020 and 2021 the figure was just 8%. In many cases, social networks help sporadic mobilisations emerge, but the shift towards horizontal coordination means the activist and strategic organisation that helped protests succeed in previous decades has been superseded.

The rise in peaceful protests has also coincided with the normalisation of violence as a political tool, both by state repression apparatus and particularly reactionary sectors of society, as shown by the widespread violence during Brazil’s electoral campaign and after the victory of Lula da Silva, as well as by the strategies of a number of far-right groups in Europe. In 2022, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association, Clément N. Voule, denounced the global trend towards militarised responses to peaceful protest and the persecution of protesters. According to the ACLED, which studies protests and political violence around the world, more cases of violence against civilians took place in 2022 than the previous year, although they have been less lethal. These figures confirm a trend of political violence growing since 2016, with around 28,000 cases worldwide, 12,000 of which were in Latin America. In Africa, the 2023 electoral calendar includes important dates around which protests can be expected against the current leaders, such as Zimbabwe and Sierra Leone, as well as increased political violence, as is the case of Nigeria, where 2022 ended with thousands acts of violence threatening the campaigns for the presidential elections at the end of February 2023.

But the United States is the paradigmatic case, where a growing proportion of the public has come to accept the use of political violence in recent years. According to a UC Davis study published in the summer of 2022, 20.5% of Americans believe that political violence is justifiable in general, and 2% – around 5 million Americans – would be willing to kill someone for a political goal. In a highly polarised context, there has been a rise in violent acts and mass shootings related to inflammatory discourse around issues like racism and LGBTI rights. This trend, together with the difficulty of adopting arms control legislation, fuels the possibility of an outbreak of violence that will destabilise the country as the 2024 presidential elections near.

7. Movements and their demands fracture and atomise

Emmanuel Macron describes it as “the end of abundance”, while some economists theorise about the “end of cheap” (be it money or production costs). A sense of exhaustion prevails: time to reverse climate change is running out; solidarity is scarce; we are losing purchasing power to meet our most basic needs; water stress is taking hold; above all, we are left with a sense of fragility. The Collins English Dictionary calls “permacrisis” an “extended period of instability and insecurity” caused by a chain of events that impact our reality. Inequalities have been growing for years, but the model now seems broken and, in the face of such profound structural change, fears and anxiety pile up.

Protest is growing in both democracies and dictatorships, but either way takes place in fractured, polarised societies. “Social cohesion erosion” is the risk that has worsened the most globally since the COVID-19 outbreak, according to the Global Risk Report 2022, and is seen as a critical threat to the world, both in the short, medium and long term.

A report Pew Research Center from November 2022 lists South Korea (90%), the United States (88%), Israel (83%), France (74%) and Hungary (71%) as the five countries analysed where the highest percentage of people say that significant division and political tension exist in their country. Polarisation is on the rise. In 2022, the Netherlands (61%), Canada (66%), the United Kingdom (68%), Germany (68%) and Spain (68%) all registered increases of over ten percentage points in citizens’ perception of political conflict between supporters of different parties, compared to the previous year.

In this context, the megatrend towards global fragmentation has even reached protest movements and their demands. The polarisation and division present in societies of both the Global North and South are replicated in social movements, even those with emancipatory aims such as improving the recognition of the rights of large parts of the population.

The feminist movement, for example, has been immersed over recent years in divisions over major issues like sex work, the definition of the subject of feminism, the conceptualisation of gender itself and the inclusion of trans people. Expressions of violence have even been exchanged by sectors of the movement with opposing opinions, disinformation has been fostered and, within the group, debates that were thought to have been laid to rest decades ago have resurfaced. In these spaces, doubt and division have frozen or stifled progressive advances due to the contradicting priorities of the different factions within the movement. This division, in turn, has opened up spaces for some conservative social, political and religious sectors to mobilise against what they consider a “gender ideology” by taking positions falsely defined as feminist. This regression threatens basic rights and liberties, as well as fuelling violent discourses against women and other groups like LGBTI+ people and migrants.

Protests in the environmental and climate change movement have evolved different strategies in recent years. At the end of 2022, new forms of protest emerged, including sensationalist actions like gluing themselves to paintings or dousing art with tomato soup, which have captured media attention and returned climate action to the public debate. The goal? To break the illusion that “everything is fine” by using actions that impact and disrupt everyday life, whether on the way to work, during a football match or a museum visit. However, some of these acts of vandalism have ended up diverting attention from the climate emergency, while the public outrage they generate can even be counterproductive for the objectives they pursue. Culture is also a common good.

In general, all these changes reflect the disenchantment many of these movements – especially young people – feel about governments’ inaction in the face of the crises that threaten us. In 2023, this disruptive activism will be even more notable, with specific calls for civil disobedience.

8. Authoritarianism under pressure

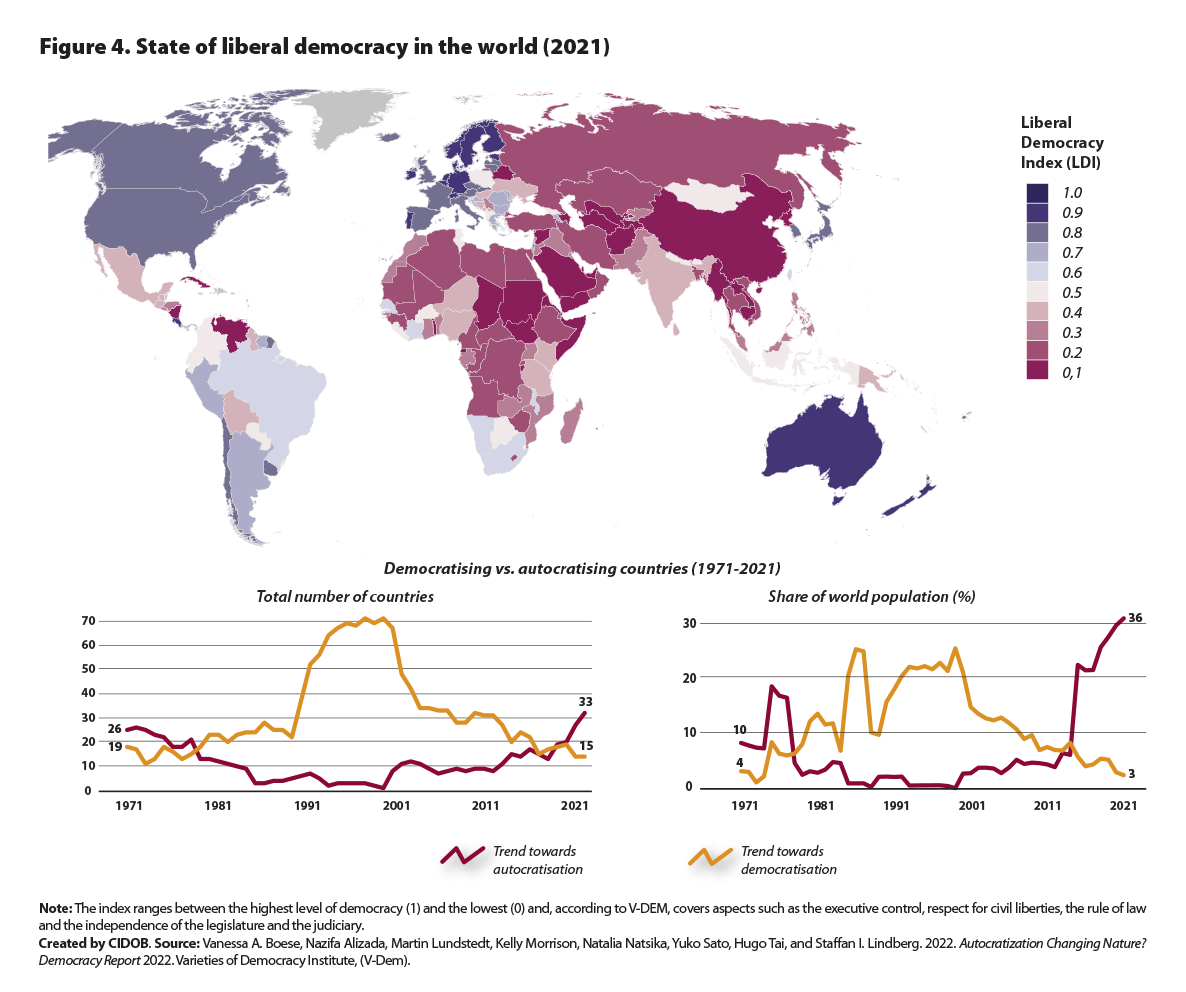

The democratic retreat continues, with 70% of the world’s population – over five billion people – living in dictatorships. The V-Dem Institute’s report on the state of democracy around the world warns that in 2022 the level was “down to 1989 levels”. That means 30 years of democratic advances have been wiped off the map. However, it is not only democracy that is under pressure. The year ahead will also raise many questions for electoral autocracies. In 2023 these authoritarian leaders are likely to be increasingly questioned, either due to internal divisions within the system itself or the strength of opposition movements.

The Iranian regime’s recent announcement that the so-called morality police would be disbanded after more than two months of protests over the death of Mahsa Amini, following her arrest for allegedly flouting Islamic dress code, is a sign of the internal pressure dividing Iran’s power elites. Tension between the security and religious apparatuses, with the leaders of the most reformist movements under house arrest or in exile, portends a complicated 2023 for the Tehran regime.

The same is true of Iran's main trading partner, China. In late October, Xi Jinping secured a third term, cementing his place as China's most powerful leader in decades, but within a month he faced the most significant protests since Tiananmen in 1989. The protests were the aggregate of the unease accumulated over three years of endless COVID-19 lockdowns, anger about local government mismanagement, and labour protests, like the one that broke out at the Zhengzhou iPhone factory. Taken separately, they may appear merely to be instances of local opposition that periodically emerge in a huge country, but together they reflect prevailing social unrest among university students, migrant workers and the middle class – those whose lives are most impacted by the changes brought by the border closures and economic slowdown.

Vladimir Putin also faces intense pressure, on nearly all fronts. Social discontent in Russia –absent from public spaces or censored – is finding other ways to protest, especially via social networks. Public support for Russia's invasion of Ukraine has fallen sharply in recent months, something that is only likely to become more noticeable the longer the war drags on. The divisions near the top of the Putinist pyramid are another source of pressure, albeit difficult to identify in the shadow cast by the president’s highly personalised power. Nevertheless, the pillars holding up the regime, such as the siloviki, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the United Russia party, the National Guard and the oligarchs, including figures with growing visibility and power in the Kremlin like Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner Group, are also pressurised by what happens on the military front. Speculation about Vladimir Putin’s political future and a Russia without him will grow stronger over the coming months.

The strong men seem to be in crisis. Jair Bolsonaro lost the Brazilian elections, while the Trumpist surge fell flat in the US midterms. In Ron DeSantis, a rising figure in the Republican Party, the former US president now has a conservative rival to measure his strength against ahead of the 2024 presidential elections. These are clear warning signs for leaders like Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his hopes of re-election against an opposition that appears more united and stronger than ever.

An eye must also be kept on what happens in Venezuela with Nicolás Maduro. The energy crisis has opened up new spaces that could present opportunities before the presidential elections scheduled for 2024. The Venezuelan opposition is currently looking to organise primaries in 2023 to choose a candidate to face the ruling party.

9. Regulatory fragmentation, sectoral deglobalisation

It is not just that our world is split into two by the bipolar US–China confrontation; parallel worlds are being configured, with spaces for interrelation. As strategic competition has grown, the inherent vulnerabilities of hyperconnectivity have been amplified. China is at the centre of both processes. The zero-COVID policy, which remains in place for now, and which blocks major Chinese international ports and impacts global supply chains, has precipitated the transformation of the globalisation model – and the process of redefinition remains ongoing.

Each new crisis increases the pressure on governments to limit risks. The global impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine on supply chains and access to global goods seems to have brought back geostrategic regionalisation, including in China itself. Officially, the government in Beijing speaks of the “era of dual circulation”, a period when the dominance of monocentric value chains built around China’s export power will coexist with the policy of localising its own supply and manufacturing chains. Indeed, Chinese-made vehicles already dominate the Mexican market, for example, and will continue to do so in 2023. Tesla manufactures half of its cars in Shanghai and SEAT has announced that its first 100% electric SUV will be released at the end of 2023 from the Volkswagen Group’s new factory in Hefei (China).

Reglobalisation seems thus to be underway, or perhaps a regionalisation of variable geometry in a context of selective decoupling – or dual circulation. Integration will continue, especially in sectors where connectivity or mutual need is vital for a sector’s development, and decoupling will occur in strategic sectors of geopolitical confrontation, such as technology, security and defence. This accelerated globalisation reset, caused by both the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, has effects beyond production centres and distribution chains. A rethink – a questioning, even, by some actors – of international governance structures and the institutional framework of Bretton Woods is underway.

China’s commercial power has been its main instrument of global influence, and its economic heft has spurred its demands for more power in international financial institutions (the IMF and World Bank). But with the debate over reglobalisation gaining traction, China has also stepped up the development of its own web of organisations and mechanisms of geopolitical influence. In January 2022, Beijing launched the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, an extensive new Asia-Pacific free trade area that includes China and several strategic US allies, like Japan and Australia. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank are other key tools that will, in recent months and through 2023, become important spaces for this geopolitical transformation. Meanwhile, the potential strengthening of the BRICS in 2023 may also bolster the role of the New Development Bank (NDB). The third Belt and Road Forum should be held next year, and will attempt to give China’s flagship foreign policy initiative under Xi Jinping new impetus with the aim of promoting infrastructure connectivity in a new phase of globalisation. However, the Belt and Road Initiative’s image has been affected in recent years by various projects being paused due to a lack of financing and even, in Sri Lanka’s case, bankruptcy. Beijing has responded with new proposals like the Global Data Security Initiative (2020), the Global Development Initiative (2021) and the Global Security Initiative (2022), which seek to address some of Belt and Road’s weaknesses. These will only be strengthened as new frameworks for Chinese foreign policy in 2023, as Beijing’s priorities pivot towards the Global South and consolidating its influence in developing countries.

Faced with this new reality, the other players in the geopolitical game have also deployed their own strategies. Washington has tightened restrictions on technological exchange with Beijing and increased its shows of support for Taiwan. The European Union has strengthened its economic muscle, with mechanisms like the anti-coercion instrument – still at the negotiation stage – which proposes a harmonised package of countermeasures against possible commercial threats by third countries, and which joins the already existing foreign direct investment regulation, which limits investments that could potentially affect the EU’s security or public order. Other recent initiatives have also been presented, such as the G7’s Global Investment and Infrastructure Partnership (2022), Joe Biden's Build Back Better World (2021), and the European Union’s Global Gateway (2021), in order to compete at a global level for these spaces of influence and development.

This proliferation of instruments that revolve around two competing nucleuses of power raises the risk of geoeconomic fragmentation, according to the IMF. This fragmentation of the world into “distinct economic blocs with different ideologies, political systems, technology standards, cross-border payment and trade systems, and reserve currencies” could also increase vulnerability and problems with accessing global public goods.

But the clash of models goes beyond the tensions between Washington and Beijing. China and Russia’s strategies may differ, but they share a global vision of challenging the liberal international order. While Vladimir Putin uses military force to try to alter the balance of power in Europe, Beijing is convinced that time and history are on its side. Russia is feeling the effects of the legal, commercial, financial and technological restrictions imposed in 2022 by 38 governments from North America, Europe and Asia in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Meanwhile, its main strategic ally, Beijing, is expanding its alternative model from a position of significant integration within the system. For example, the blocking of Russia’s use of the SWIFT international payment system in 2022 strengthened the Chinese yuan’s internationalisation on the markets, as a safe haven currency and one for use in commercial transactions.

10. Testing limits

In 2023 individual and collective limits will be tested. The black ball on our pool table is the unexpected event or effect that can – as recent years have shown – smash international political forecasts, timelines and strategies. Among the threats that could escalate existing risks is the greatly increased danger of a nuclear attack or accident since Russia stepped up its rhetoric in recent months and bombings took place near nuclear power plants like Zaporizhzhia in south-eastern Ukraine.

Of the world’s 12,705 nuclear weapons, around 2,000 – practically all belonging to Russia and the United States – are in a state of high operational alert. What is more, in 2022 North Korea launched eight intercontinental missiles and conducted tests on over 60 missiles, with over 23 launched in a single day. South Korea warns that the question is not whether a new nuclear test will take place, but when. Meanwhile, Kim Jong-un’s modification of North Korean nuclear doctrine has led Seoul and Washington to announce new sanctions.

In 2023 we will watch closely to see the reach of the shock wave caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russian tanks entering its neighbouring country led many to speculate that Taiwan would be the next global confrontation, especially with tensions rising this summer following Nancy Pelosi's visit to the island and the military response from Beijing. The two cases are extremely different, but a conflict in the Strait cannot be completely ruled out. An invasion and forced reunification of Taiwan would, however, generate an unprecedented shock in the world economy as well as unforeseeable geopolitical consequences and high economic, political and diplomatic costs for China. Maritime trade and the airspace of the South China Sea, through which about a third of global trade passes, would be disrupted indefinitely, affecting many global value chains. According to RAND, a year of conflict in the area would reduce China's GDP by 25%–35% and US GDP by 5%–10%. The Taiwanese economy would be completely destroyed and isolated from international trade, with serious consequences for semiconductor supply chains and the infrastructure of TSMC, which produces about 54% of the world's most advanced semiconductors and on which large companies including Apple and Nvidia depend.

Russia’s neighbourhood is another site of potential destabilisation. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has not only weakened Vladimir Putin's image at home, but also as an actor providing stability and security in the post-Soviet space. The recent fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and the more recent clashes on the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, are symptomatic of this background geopolitical shift. Meanwhile, the European Union is closely monitoring the situation in Moldova for fear that it could be the next domino to fall. With part of its territory, Transnistria, controlled by Russian troops for decades and 100% dependence on Russian gas, it is extremely vulnerable.

Increasingly aggressive meteorological phenomena could also put insufficient global responses to the urgent climate crisis to the test in 2023, especially if new related risks emerge, like Natech – natural hazards triggering technological accidents. The latest IPCC report concludes that the effects of climate change have already caused irreversible damage to the environment and people’s well-being. The 2022 floods in Pakistan and Nigeria, the heat waves in India and the persistent drought in the Horn of Africa are clear examples of the unpredictability and impact of these events, which increase the numbers of people forcibly displaced by the destruction of the environment and undermine the livelihoods of millions of people around the world.

Temperatures in Africa, and specifically in the Sahel, are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average. However, climate risks are not the only crisis that could affect the continent. Rising tensions, regional conflicts becoming chronic, electoral contestation and the instability linked to the jihadist movements in the Sahel and their possible expansion towards the Gulf of Guinea could worsen the region’s security situation. What is more, the uncertain post-pandemic recovery, the effects of multiple energy, public goods and debt crises, and the existing social discontent could bring a cascading crisis in Africa in 2023. The consequences, which would be disastrous for the continent’s development and the well-being of its people, would also have major impacts for the actors engaged in regional stability, adding a new global crisis to an already long list.

The continued instability of the permacrisis and the threat of an as-yet-unknown eight-ball do not diminish the need either for action or to reconceive the new cooperation frameworks in order to handle global crises and permanent uncertainty.

Calendar CIDOB 2023: 75 dates to mark on the calendar

January 1 - Renewal of the United Nations Security Council. Ecuador, Japan, Malta, Mozambique and Switzerland will join the UN Security Council as non-permanent members, replacing India, Ireland, Kenya, Mexico and Norway, whose terms end.

January 9–10 - North American Leaders’ Summit. Mexico hosts the so-called “Three Amigos Summit” (featuring Mexico, Canada and the United States), where issues such as extreme poverty, migration, security, energy, regional governance and trade will be addressed.

January 16–20 - Davos Forum. Annual meeting gathering major political leaders, senior executives from the world’s leading companies, heads of international organisations and NGOs, and notable cultural and social figures. This year, under the slogan "Cooperation in a Fragmented World", some of the main shared global challenges will be addressed, as well as the need to work jointly to resolve them in an increasingly complex geopolitical setting. The war in Ukraine will be at the centre of the discussion.

January 27 - 50th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords. The agreements signed by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the government of South Vietnam, the United States and the National Liberation Front market the beginning of the end of the Vietnam War. Three years later, on July 2nd, 1976, the country was reunified under the name of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

January 31–February 5 - Pope Francis visits the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan. The pontiff’s first scheduled overseas trip of 2023. He is expected to address some of the common problems both countries face, relating to humanitarian issues, social tensions and poverty.

February - African Union Summit. As current AU chair, Senegal will organise the summit, with a number of fronts open across the continent: global food insecurity, which is hitting Africa particularly hard, aggravated by the war in Ukraine and natural disasters; governance abuses and democratic regression on the continent, with four countries (Burkina Faso, Guinea Conakry, Mali and Sudan) suspended from the AU; increased violent extremism in the Sahel and Mozambique; tensions between Algeria and Morocco; and the frameworks of the AU’s relationships with China, the United States, the European Union and Russia.

February 5 - Regional and local elections in Ecuador. These elections, to decide the country's main mid-level elected positions, will be coloured by the current security crisis, which has led to periodic declarations of states of exception and emergency, raising social and political tensions in the country.

February 5 – Presidential elections in Cyprus. Rising tensions with Turkey in Northern Cyprus will be a central issue in the elections in a year marked by electoral timing in the main countries embroiled in the conflict. With a record number of candidates, should none get a majority in the first round, the elections will be decided in a runoff on February 12th.

February 17–19 - 59th Munich Security Conference. The annual meeting of the largest independent forum on international security policies, which brings together high-level figures from over 70 countries. The war in Ukraine, transatlantic security relations, US–China technology conflicts and the inclusion of security perspectives from the Global South will be the main focuses of debate and discussion.

February 25 - General election in Nigeria. Asiwaju Bola Tinubu, from the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) party, and former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, leader of the opposition Peoples' Democratic Party (PDP), will vie to replace Muhammadu Buhari, who leaves office after two terms. As well as the usual challenges of poverty reduction, insecurity problems and Nigeria's leadership in the region, there will be growing internal social tension, which threatens to increase instability and the pressure on Nigerian democracy.

February 26 - 20th anniversary of the war in Darfur. In 2003, the government of then President Omar al-Bashir launched a military operation against rebel insurgent groups in the Darfur region, causing one of the largest humanitarian crises in North Africa, forcibly displacing millions of people and leading to over 300,000 deaths. Al-Bashir fell in a coup in 2019 and the International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued two warrants for his arrest for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes related to Darfur.

February 27–March 2 - Mobile World Congress. Barcelona hosts the world’s largest mobile phone event, which gathers the leading technology and communication companies. This year, with velocity as the focus, it will revolve around 5G technology, with five main themes: 5G acceleration; immersive technologies and next-generation mobility; mobile networks; the acceleration of mobile banking and the evolution of digital currencies and their role in digital economy transactions around the world; and the expansion of digital technologies.

February 28 – 25th anniversary of the start of the war in Kosovo. The last armed conflict in the former Yugoslavia was between the separatist Kosovo Liberation Army and the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, then formed of Serbia and Montenegro. It ended with military intervention by NATO and the signing of the Kumanovo Agreement. In 2008 Kosovo proclaimed its independence from Serbia and has so far been recognised by over 110 countries.

March 8 - International Women's Day. Now a key date on many countries’ political and social agendas, because in recent years – especially in Latin America, the United States and Europe – mass demonstrations have gained momentum around a common goal: the fight for the rights of women and gender equality around the world.

March 20 - 20th anniversary of the invasion of Iraq. Saddam Hussein's government was brought down following a military intervention led by the United States and United Kingdom, with the support of countries like Portugal and Spain, under the pretext that Iraq had access to weapons of mass destruction. A Coalition Provisional Authority was given power for just over a year until an interim Iraqi government was established.

March 20–21 - Second European Humanitarian Forum. Promoted by the European Union – one of the world’s leading humanitarian donors – political leaders, humanitarian organisations and other partners will gather at a time of particular international relevance in terms of human security, with the impact being felt of the war in Ukraine, rising global food prices and natural disasters in fragile settings.

March 22– 24 - United Nations Water Conference. New York will host one of the year’s key environmental events. Governments, the private sector and civil society will gather to advance on the achievement of the 2030 Agenda’s SDG 6, at a time of major tensions over water in large areas of the world. This year’s event will focus on five major themes: water for health; water for sustainable development; water for climate, resilience and environment; water for cooperation; and the Water Action Decade.

First Quarter - France–UK Defence Summit. Emmanuel Macron announced the holding of this summit with the aim of establishing strategic priorities for both countries in response to global geopolitical tensions, especially the invasion of Ukraine, the growing tensions with China, and the insecurity in the Sahel. The need to increase European strategic military autonomy will also play a major part in the discussion.

April 2 - General election in Finland. Sanna Marin, the current prime minister, will seek re-election in a turbulent geopolitical context for Finland that began with the war in Ukraine and led to the historic foreign and defence policy shift of requesting NATO membership. The request remains ungranted due to the reluctance of two member states, Hungary and Turkey.

April 2 - 10th anniversary of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). The tenth anniversary of the largest multilateral treaty regulating the international trade in conventional weapons. Over 110 countries, including six of the world's top ten arms producers (China, UK, Italy, Spain, France and Germany), have ratified or joined the ATT.

April 10 - 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreements. Laid the groundwork for bringing three decades of conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland to an end. Approval led to the cessation of violence and the reinstatement of self-government for Northern Ireland.

April 23 - Legislative elections in Guinea-Bissau. Elections will be conditioned by the attempted coup of February 2022, the dissolution of parliament by President Umaro Sissoco Embaló in May, and the delay in calling the elections, which raised political and social tensions in the country.

April 26–28 - First Cities Summit of the Americas. Denver will host the first of these meetings, which aims to promote regional cooperation between the main cities on the American continent in the fields of public health, the environment, digital technology and security. This initiative emerged after the Summit of the Americas in June 2022.

April 30 - General election in Paraguay. The president and vice president will be up for election, along with all members of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, 17 governors and departmental boards, and the Mercosur Parliament. Paraguay’s current presidents and vice presidents are not eligible for re-election. The elections take place in a rarefied political and social environment, amid accusations of corruption, narco-government and an increased presence of transnational organised crime in the country.

May 4 - Local elections in the United Kingdom. The first electoral barometer of the support for the country’s main political parties after the political crises generated by the resignations of Conservative prime ministers Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak’s rise to the leadership.

May 6 - Coronation of King Charles III and Queen Consort Camilla. Westminster Abbey will host the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Consort Camilla, after the death of Queen Elizabeth II on September 8th ended her 70-year reign.

May 7 - General election in Thailand. The current prime minister, Prayut Chan-o-cha, seeks re-election as the opposition hopes for victory after several years of successive political and social crises: from the 2014 coup that brought Prayut to power with the establishment of a military dictatorship, the contested elections of 2019 and the on-going popular protests for democracy since 2020.

May 19–21 - 48th G7 Summit in Japan. Hiroshima will host the latest G7 summit with the Ukrainian crisis and its impact on geopolitics and the international economy on the agenda.

May 25 - 50 years since the founding of the Organization of African Unity. The OAU was the forerunner of today’s African Union, which was created in 2002. The OAU’s foundation promoted a pan-Africanist vision of the continent and of international relations, thanks to the political activism of African leaders like Haile Selassie I, Kwame Nkrumah, Gamal Abdel Nasser and Julius Nyerere.

May 28 - Regional and local elections in Spain. A new electoral cycle begins in the country with the elections for local governments and many regional governments, a few months before the general election. The agenda will be set by an environment of growing political and social tension – with the impact of the pandemic still being felt –, the distribution of the Next Generation EU funds and the war in Ukraine.

June 5 - 10th anniversary of the Snowden case. Ten years have passed since hundreds of classified documents were leaked to various media outlets, compromising US intelligence services and raising questions about the role of the world's leading technology companies.

June 18 – Presidential and general elections in Turkey. The country's current president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, will run for office again in an election the opposition hopes to win. To this end, six opposition groupings have created a political alliance, hoping to capitalise on widespread discontent among the population about the country's critical economic situation.

June 20 - World Refugee Day. In 2023, the number of forcibly displaced people –including both the internally displaced and refugees – will again reach record numbers, with the war in Ukraine driving this year’s rise and the impact of aggressive climate events in Africa and South Asia. This week in June will see the release of UNHCR's annual report on forced displacement trends around the world.

June 24 - Presidential, parliamentary and local elections in Sierra Leone. President Julius Maada Bio will stand for re-election in the midst of a severe economic and energy crisis that has increased the prices of food, electricity and fuel and raised social tensions over recent months, with large-scale demonstrations and protests in major cities across the country.

June 25 - General election in Guatemala. Guatemala holds elections for the country's presidency and vice-presidency, all the deputies in Congress, over 300 municipal mayors and the members of Parlacen. Security, corruption, immigration policies, the impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine on the country's economy, and the severe effects of climate change on the agricultural sector will be the key issues in the electoral campaign.

July - General election in Greece. Hopeful of an electoral breakthrough, New Democracy, who currently hold power, the main opposition party, Syriza, and the alliances that may be formed with third parties, will vie to win elections shaped by the economy and the impact of the war in Ukraine. Both the current prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, and the previous one, Alexis Tsipras, have announced their intentions to stand as leaders of their respective parties.