War in Ukraine and the gas crisis force a rethink of EU foreign policy

EU member states’ utter dependence on Russian supplies make gas a key factor in the crisis provoked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Germany’s realpolitik towards Russia in recent decades has left it weakened, as it has allowed Russia to weaponise gas.

Hegemonic US power has frequently been used over the past seven decades to ensure European allies’ energy security. Europe’s failure to undertake coherent collective action to sort out its dependency on gas imported from beyond its borders has been worsened by the decline of its domestic production, which covers 42% of its requirements compared with 53% a decade ago.

The crisis will force a major rethink of Europe’s gas security over the next decade. This will include diversifying outside sources of gas – starting with suppliers that are close by, such as Algeria and Libya, as well as looking further afield in Africa and the Americas; and increasing gas exchanges within Europe by helping Spain become a major gas hub and ensuring gas stocks are much higher than the historic lows they reached last autumn.

As European gas prices hit an all-time high this week with futures linked to Title Transfer Facility (TTF), Europe’s wholesale natural gas price rose more than 40% to €173 per megawatt hour (on March 3rd). Natural gas prices in Europe are currently the equivalent of $225 per barrel of oil equivalent. That is an astronomical rise. In the US, the price of a similar unit is $5. Meanwhile, oil prices rose to their highest level in nine years with Brent crude reaching $118.22 a barrel.

Gas prices are sky high because Europe has no substitute for natural gas from Russia, the largest exporter both worldwide (260 bcm/year [Billion cubic metres]) and to the old continent (160 bcm/year, or 45% of total European imports). The spot market for gas is relatively small compared to oil. Most gas is not traded as liquid natural gas but is transported by pipeline that can only service certain markets. Hence there is very little gas which can be redirected to Europe and what can be redirected is very expensive. This explains the vast disparity in prices between Europe and the US and why the US has been encouraging buyers and sellers to break their contracts to allow Europe to restock its inventory. Inventories in Europe have been at historic lows since last autumn because prices were high and the Russians had already cut back their supply. Low inventories, a perception of scarcity and unchanged levels of demand created the conditions for a perfect storm – a fear factor and actual shortage which drove prices up.

Hegemonic US power has frequently been used over the past seven decades to ensure European allies’ energy security. Yet in Libya and the Global Enduring Disorder Jason Pack explains that waning American geopolitical hegemony has injected more uncertainties into the supply chains for various products. Simultaneously, he sees many neo-populist leaders conspiring with Vladimir Putin to promote high energy prices while promoting fears of future shortages out of a conviction that this increases Russian geopolitical leverage. One can extrapolate from Pack’s framework that coordination failures among major importing European states have led to failures to undertake proactive collective action to decrease their structural volatilities

The leading cause of the current crisis is therefore part and parcel of this “Enduring Disorder” – the European failure to undertake coherent collective action to sort out Europe’s dependency. EU domestic gas production has declined by a quarter over the past ten years and now covers only 42% of consumption, as compared with 53% in 2010. The decline is mainly the result of the closure of the Groningen gas field, which is well underway and will be completed by 2030.

Six points need to be considered to understand where we go from here:

- European countries’ dependence on Russian supplies of gas varies

- There are no miracle solutions in the short term

- Russia needs the income from gas and Europe cannot live without gas

- Germany’s realpolitik towards Russia has failed

- Spain as a gas hub?

- The crisis will force the EU to rethink its foreign policy.

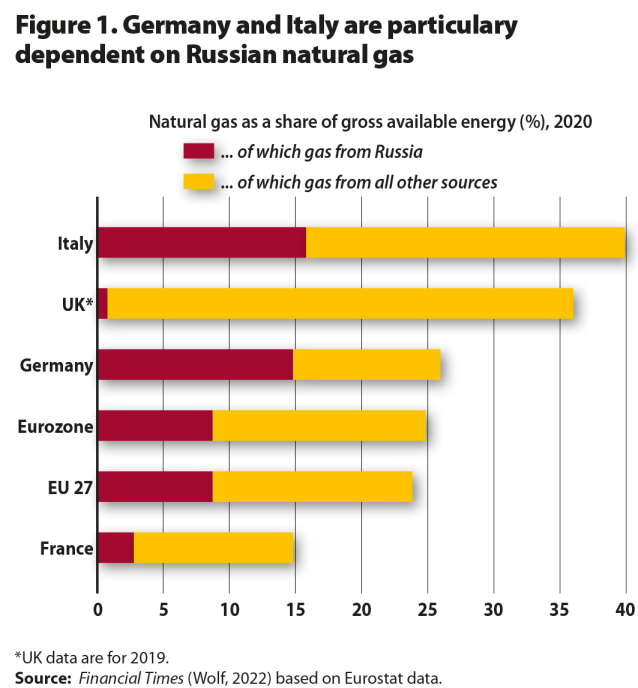

1. European countries’ dependence on Russian supplies of gas varies

Russian gas provides 45% of Europe’s total gas imports. Russia is also Europe’s main supplier of crude oil (3.1 million b/d or 29%) and refined products (106 MMT/year or 51%). Spare capacity in oil production is concentrated in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Both countries are hedging their bets, as they believe successive US administrations have been disengaging from the Middle East and have been disgruntled with US policies since former president Barack Obama was perceived to have ignored the interests of America’s long-term Sunni Arab partners during the 2011 popular uprisings and when he signed up to the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran. Spare production for natural gas, except in Russia and Qatar, is negligible.

Daleep Singh, the US Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economics is clear that sanctions are “not designed to cause any disruption to current flows of energy from Russia” to Europe. They may be “massive”, but some breathing space is left for Russia’s economy, an opportunity that was denied in Iran’s case.

The dependence of individual EU countries on Russian supplies varies considerably. Russia accounts for 60% or more of gas imports for the Czech Republic, Latvia, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Finland and Germany. This percentage falls to 40% for Italy and 20% or less for France, Sweden, Spain and Portugal. Nuclear power is France’s main source of energy and Spain has a dependable supplier in Algeria, from which it has been buying gas since the first shipments of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Barcelona were pioneered by Pedro Duran Farell in 1969. The importance of nuclear power in a country like France, the major role of coal in a country like Poland, and a confused debate about energy transition (few politicians have grasped the importance of natural gas during the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy) have all contributed to the serious energy crisis the EU faces.

2. There are no miracle solutions in the short term

The message delivered by the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) in Doha (Qatar) last weekend was that an increase of non-Russian gas to Europe comes up against two limits. They are summed up in the February 28th issue of World Energy Weekly (WEW): First, global production capacity is by definition limited. Second, “there are significant constraints where export possibilities are concerned, as a large proportion of capacity (including LNG) is already contracted over medium or long-term, mainly with Asian markets.” During the summit, Russia’s minister of energy, Nikolay Shulginov, emphasised that Russians are “fully committed to existing contracts”, thereby “remind[ing] Europeans of Moscow’s position: long-term gas agreements offer significant protection to buyers in terms of volumes and prices”. It is a point the EU’s dash to liberalise gas markets since 2000 has quite overlooked. The Qatari minister of energy, Saad Sherida al-Kaabi, explained that the fundamental reason for current gas prices is lack of investment. In the short term, conditions will remain difficult and volatile.

3. Russia needs the income from gas and Europe cannot live without gas

Russia and Europe are joined at the hip, at least when it comes to energy. Hence, shock and awe sanctions on Russia would hurt Europe as much as Russia. Revenue from energy exports accounts for 40% of Russia’s federal budget, which is why some observers dismiss the idea that Russia would turn off the energy pipelines as far-fetched. It wants to be seen as a reliable partner. But there are no simple solutions: Russia needs the income and Europe cannot live without the oil and gas. The EU–UK approach to sanctions does reflect an understanding that Russia is at least as dependant on its gas sales to Europe as European economies are on burning that gas.

Beyond gas, Russia remains a key commodity exporter. It supplies about 40% of the world’s palladium, which is needed in the catalytic converters used in vehicles to limit harmful emissions, about 30% of titanium, an important component for metal alloys, and (with Ukraine) 40–50% of neon, a by-product of steel manufacturing, which is a critical raw material for chip production. When Russia entered eastern Ukraine in 2014, the price of neon jumped 600%, causing disruption in the semiconductor industry. Russia’s influence extends to farming and the food industry. Belarus is a leading exporter of potash, a key input in the production of certain fertilisers. Western sanctions against Belarus forced up prices and led China and Russia, also large fertiliser exporters, to put in place export curbs to safeguard domestic supply. As it is, shipments of wheat – Russia and Ukraine account for almost one-third of global shipments – have already been disrupted, leading to a jump in prices of wheat futures traded in Chicago by 13% to $11.32 a bushel.

Will Russia thwart Western countries by limiting supplies of such raw materials and commodities? Some analysts suspect that growing Russian influence in former Soviet states “could eventually create a situation where Moscow has strong influence over the global grain markets” (Terazono et al., 2022). Thus, after gas, food risks being weaponised in some strategic game.

4. Germany’s realpolitik towards Russia has failed

A fourth element to be considered in this crisis is that Germany “has been weakened: its realpolitik towards Russia has failed”, with Pierre Terzian (2022)’s harsh judgment widely shared by oil and gas executives. Critics argue that a realpolitik built on such reliance on gas supplies from one source, especially Russia, made no sense. Nor did switching off Germany’s nuclear industry after the Fukushima disaster. The result was greater use of coal in a country whose leaders constantly boast of their green credentials.

Back in 1978, Germany contracted to buy Algerian LNG and build the necessary regasification terminals. That would have diversified Germany’s non-EU suppliers of gas at a time when the first major gas pipeline to Russia was being built. Yet Germany walked away from that contract, as did the Dutch, who had also agreed to buy LNG from Algeria. No explanation was ever offered to Algeria. When he visited Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in 1983, President Ronald Reagan told his host he was encouraging the building of a pipeline to carry Algerian gas to the Iberian Peninsula (the Maghreb–Europe pipeline was built ten years later and inaugurated in 1996). According to Schmidt, the French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing held the fantastical belief that Russia was a more reliable supplier than Algeria.

5. Spain as a gas hub?

The history of gas tells us LNG was invented by Shell in Algeria between 1961 and 1964. The first ever shipment of LNG was carried from Algeria to the UK in 1964. Algeria has respected all its gas export contracts to European customers since then, be they in LNG form or via underwater pipeline. When a political dispute with Morocco closed the Maghreb–Europe pipeline on November 1st 2021, Algeria assured that neither Spain nor Portugal would be in need of gas, which is delivered either by LNG ships or transits through the Medgaz pipeline from Algeria to Spain which was inaugurated in 2004.

Spain, for one, could contribute more to Europe’s gas security if the connections between the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe were developed (Riley and Ghilès, 2018). Spain boasts one-third of Europe’s LNG import capacity, much of it unused, and is connected to Algeria by two major pipelines (including the one closed since November 1st last year). But the Iberian supply routes to the rest of the EU are restricted by France’s refusal to allow any increase in the 7 bcm gasline that carries gas northwards. The main blocking factor is the French lobby that protects its nuclear industry. An Iberian solution would not only benefit Spain and France but also Algeria, creating additional incentives to explore for and develop new gas fields, exploit shale gas, of which the country boasts the third largest reserves in the world, and kickstart a domestic renewables revolution. Libya’s gas reserves are at present modest but much of the country, especially its potentially promising offshore zones, remain unexplored. Algeria has 4,500 bcm of proven reserves and 20–25 tcm (trillion cubic metres) of unconventional gas reserves, the third-largest in the world after the US and China (Argentina’s reserves are similar to Algeria’s). How much gas that could produce is anyone’s guess. Algeria today produces 90 bcm, of which 50 bcm were exported last year. Algeria also boasts huge storage capacity – 60 bcm – at the Hassi R’Mel gas field, its oldest and largest, as compared with the EU’s storage capacity of 115 bcm. Strengthening its gas ties with Algeria and Libya would fit with the EU’s professed policy of strengthening its relations with Africa.

Libya is currently facing a moment of turmoil as two rival leaders claim to be the country’s prime minister. Jason Pack (2021) points out that now would be a key time for nations with previously rival approaches towards the Libyan conflict, like France and Italy, to finally bury the hatchet and invest real money and political capital in Libya’s stabilisation and coherent economic reconstruction. It is in their financial as well as geostrategic interest, as the Italian ENI and the French Total Energy would be the prime winners of greater Libyan gas exports to Europe.

6. The crisis will force the EU to rethink its foreign policy

If Europe decides to move beyond Russian gas, which over a 5–10-year period is an available option, Russia’s only remaining market will be China. This, argues Anatol Lieven (2022), will put Russia completely in China’s pocket, with implications for the price of gas, as it becomes a buyer’s market for China. In the longer run, Russia will become a raw-material supplier to China. This is something the Russian elites dread and would not be risking if they felt the West had left them much choice in the matter. In turn this throws up the question of the always-complex Sino-Russian relationship. A better understanding of the Sino-Russian relationship is essential to better understanding the gas crisis in Europe. Terzian (2022) writes that “it would be in China’s interest to see Russia emerge from this crisis neither too weak nor too strong. It wants Russia to help establish a new international order, while also needing China’s support in several areas. For historical reasons, the Chinese are still suspicious of the Russians”. The Russian–Chinese statement of February 4th, when President Putin visited his Chinese counterpart for the inauguration of the Winter Olympics, suggest the two countries “do not seem to be in complete agreement on the exact definition of the ‘new order’ they want.” (ibid.) They do not have the same priorities now, just as they did not during the Cold War. For Russia it is NATO; for China the new international order.

Conclusion

In the short-term Russia holds at least a military advantage, but current thinking is that in the longer term Western countries and China will have the upper hand. How far Russia goes is the critical question, but however this crisis ends, the EU is going to have to think about how it can live with the new alliance being built between Moscow and Beijing. Strategic thinking here will have to include energy security, climate change and relations with China, but also its near abroad in the Mediterranean and, beyond that, Africa.

References

Lieven, Anatol. “What is Moscow thinking? The brutal calculations behind Russia’s attack on Ukraine”. The Signal (22 February 2022).

Pack , Jason. Libya and the Global Enduring Disorder, Hurst, 2021.

Riley, Alan and Ghilès, Francis. “The Iberian Solution could offer Europe more gas”. World Energy Weekly (WEW) (21 September 2018).

Terazono, Emika; Hume, Neil and Files, Nic. “War in Ukraine: when political risks upturn commodity markets”. Financial Times (March 2022) (online) . [Accessed on 07.03.2022] https://www.ft.com/content/cf0212cf-21f3-4520-ae5f-136ce3f78afc

Terzian, Pierre. “Scope and consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine”. CIVILNET (28 February 2022) (online). [Accessed on 07.03.2022] https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/652021/scope-and-consequences-of-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine/

Wolf, Martin. “Putin has reignited the conflict between tyranny and liberal democracy”. Financial Times (FT) (01 March 2022) (online). [Accessed on 07.03.2022] https://www.ft.com/content/be932917-e467-4b7d-82b8-3ff4015874b3

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/NotesInt.2022/268/en

E-ISSN: 2013-4428