Unaccompanied Young Migrants Outside Reception Systems: A Diagnosis of the Case of Barcelona

* This CIDOB Briefing is the result of a discussion that took place at a closed-door seminar at CIDOB with representatives of the Generalitat (Government) of Catalonia, the Barcelona City Council, and the leading social entities in the field. It was held as part of CIDOB’s Global Cities Programme with support from the NIEM (National Integration Evaluation Mechanism) project, which is co-financed by the European Union Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF).

This CIDOB Briefing analyses the situation in Barcelona of unaccompanied young migrants after they have come of age. First, it studies the regulatory and structural factors that intensify their vulnerability once they have left the care provided by child protection mechanisms. Second, it examines what the City of Barcelona is doing to support them in the deinstitutionalisation process and to remedy situations of social exclusion. The conclusions identify what remains to be done and offer a series of general recommendations.

1. Diagnosis of the problem

In recent years, the numbers of foreign minors arriving Europe without family members have greatly increased. In Spain, the number of unaccompanied foreign minors has tripled in three years, from 3,997 in 2016 to 12,417 in 2019. In Catalonia, the figure also tripled, from 1,041 in 2017 to 3,450 in 2018. In 2020, it was estimated that a total of 2,352 minors had migrated to Catalonia and were alone. Since the majority of the new arrivals are aged between 16 and 18, these rising figures have meant, in just a few years, an almost immediate increase in the numbers of young migrants who are on their own when they come of age and leave child protection facilities.

Although they are often grouped together under the same heading of unaccompanied foreign minors (Menors Estrangers No Acompanyats, MENA), their profiles are very diverse. In Catalunya, it is estimated that 59.9% have emigrated because of lack of opportunities at home, 54.7% are fleeing from poverty, and 51% have left for reasons of employment. Family consent about the project of migrating also varies as does the socioeconomic situation and geographic origin of the family (if these young people have a family). Nevertheless, their expectations concerning their destination are not so diverse: 89.5% expect to find work, 52.6% to get some sort of training (especially with regard to finding employment), and 42.9% to regularise their situation. All these factors show the heterogeneity of the group itself.

What is common to all unaccompanied minors is the regulatory and structural context they find once they are in Catalonia. As minors, they are wards of the Direcció General d’Atenció a la Infància i l’Adolescència (DGAIA – Directorate General for Child and Adolescent Care) of the Generalitat (Government) of Catalonia. When they come of age, they leave the child protection facilities. While it is true that some remain linked with the Generalitat’s support service for young people leaving care (Àrea de Suport al Jove Tutelat i Extutelat – ASJTET), others (whether they have been wards of the state in Catalonia or not) are left out. In general terms, their situation is seriously limited by structural factors that directly exacerbate their vulnerability.

The first factor is access to documentation. Many of these minors have come of age without having achieved residence or work permits. Hence, from one day to the next, they have gone from being minors under the protection of the administration to adults who are excluded (or not recognised) by the Spanish Aliens Act. Being undocumented means not having the right to work and, in many cases, major obstacles to accessing social services and benefits. For example, without a residence permit, it is impossible to obtain the benefits for young people leaving care, the minimum living income, or the minimum income of citizenship. However, the problem is not only access to documentation but also the ability to retain it. Two rulings of the Supreme Court (STS 1155/2018 and STS110/2019) have tightened criteria, requiring that young people applying for renewal must demonstrate an income of their own of 537 euros per month the first time (at the age of 18) and 2,151 euros the second time (at the age of 19). This means that many of the young people have been condemned to a situation of irregularity and, accordingly, have been automatically excluded from access to housing and training programmes.

The second background factor is problems of access to the job market. For these young people, the difficulty is twofold. First, without a work permit, they cannot achieve an employment contract, which means that it is impossible for them to work or to find any formal employment. Second, the job market itself does not help the situation as a sizeable proportion of young people (including highly qualified nationals) are in situations of structural unemployment and/or highly precarious employment conditions. More specifically, in Barcelona some 30% of young people aged between 16 and 24 are unemployed.

The third contingent factor is access to housing. As one young migrant remarked, “Without papers there’s no work, and without work, there’s no home”. Once again, the barrier is twofold and thus difficult to surmount. First of all, the more precarious the legal status, the more precarious the housing situation. In particular, without a residence permit, it is difficult to gain access to the housing market and also to the “emancipation flats” provided by the Generalitat’s support service for young people leaving care (ASJTET). Added to this barrier is, once again, the general situation in which housing prices have risen over the last decade despite wage stagnation. Hence, it is not surprising to see that the numbers of homeless unaccompanied young migrants are rising. In 2019, the Xarxa d’Atenció a Persones sense Llar (XAPSLL – Support Network for the Homeless) reported that 389 unaccompanied young migrants aged between 18 and 30 were sleeping in its shelters, and another 150 were sleeping rough while waiting for accommodation.

Given this situation of serious social exclusion and increased vulnerability of unaccompanied young migrants who have come of age, the aim of this CIDOB Briefing is to analyse what has been done in Barcelona and what else could be done. In addressing these issues, we have carried out a series of in-depth interviews with the main actors involved and, in a second phase, have organised a closed-door working session with representatives of the Generalitat of Catalonia, the Barcelona City Council, and the leading social entities working in the area. Although this report incorporates their views, the resulting text is the sole, exclusive responsibility of the authors.

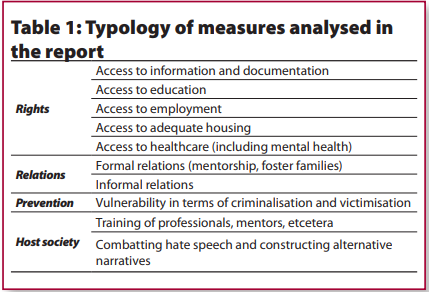

In structuring our analysis, we have produced a typology of measures (see Table 1). The first block covers the measures that safeguard or facilitate access to basic rights: access to information and documentation; access to healthcare; access to education and training; access to employment; and access to adequate housing. The second block includes measures aiming to foster social ties, either formal (through mentorship, foster families, etcetera) or informal (with people of the same age, community, etcetera). The third block shows the measures taken with the aim of preventing factors that increase the vulnerability of these young people in terms of criminalisation or victimisation. Finally, understanding that any kind of integration is a two-way process, we analyse measures pertaining to the host society, from training of professionals working with unaccompanied young migrants to narratives about them, with particular attention to the struggle against hate speech and promoting alternative kinds of discourse.

2. Diagnosis of policies

The first major barrier and a basic factor of exclusion and increased vulnerability is access to documentation. In this regard, the Barcelona City Council has an active residency registration policy, which is to say it facilitates registration in the local census (in Spanish, el padrón) in all cases, independently of the person’s administrative status and/or residential situation. While registration in the local census guarantees better access to basic public services (like education, healthcare, and other rights and services coming under local or regional jurisdiction), it is no substitute for lack of a residence, or residence-and-work permit. With a view to facilitating regularisation, the City Council has reactivated the Xarxa d’Entitats Socials d’Assessorament Jurídic en Estrangeria (XESAJE – Network of Social Organisations for Legal Advice to Foreigners and Immigrants), which includes the city’s social organisations providing legal advice free of charge. The Council has also promoted job placement programmes which, through recruitment grants, aim to facilitate access to employment offers, which is the sine qua non condition for regularisation through arraigo (social roots procedure).

As for access to education, most facilities for unaccompanied young migrants offer some kind of training. The problem is that, in most cases, this is unregulated and/or initial basic training. This, in part, responds to the educational deficiencies of unaccompanied young migrants, of whom only 27% have completed primary schooling (FEPA 2019), as well as their linguistic difficulties in the first years after arrival. Furthermore, many facilities have so far been created in response to an emergency situation—first because of the growing numbers of arrivals and then the pandemic—with the aim of opening residential spaces or shelters (in this case, day centres) rather than providing tools and supporting the young migrants (from the educational sphere as well) in the process of social inclusion. Another more structural shortcoming appears with the limitations of the systems of professional training and their lack of integration with labour market demands (for example, by means of internship contracts).

Access to employment is another major impediment to social inclusion in the case of unaccompanied young migrants. According to data from 2019, only 27.6% of those within the reception system had income from paid work, while 40.4% were receiving some money from public funds. It is true that projects like those of ASJTET (support service for young people in or leaving care), Garantia Juvenil (Youth Guarantee), and Via Laboral (Via Work) facilitate access to training for entering the world of work. Furthermore, many reception facilities have programmes of social and employment counselling services, which are also provided by third-sector organisations. Nevertheless, all these efforts are seriously hampered if the young migrants do not have a work permit afterwards. For example, during the pandemic, only young people with an NIE (Foreigners Tax Identity Number) were able to work in the Lleida fruit picking campaign. The area of “Young People in or Leaving Care” of the Generalitat’s Work and Training Programme (beginning in July 2020) facilitates access to job offers but, once again, a residence permit is a requisite for taking part in the programme. Recently, the Barcelona Youth Network (Xbcn), created in 2018 by the Barcelona Social Services Consortium, has presented a report with proposals for helping young people gain access to the world of work by means of internships in companies, as well as specific measures for modifying the immigration regulations.

Some progress has been made with regard to housing but there is still much to do. In 40.7% of cases, housing support services take the form of “emancipation flats” for young people aged between 18 and 21. Most of them spend between one and two years in flats rented by the entities. In 2019, FEPA (Federation of Entities with Projects and Assisted Housing) assisted 2,117 unaccompanied young migrants with housing resources. As for housing facilities specifically designated for the homeless, the City of Barcelona had the following resources at the end of 2020: BarcelonActua had 87 places in three centres plus five foster families; the Maria Freixa Centre had 21 places; and Iniciatives Solidàries had 12. The Montgat Centre, which opened during the pandemic, was attending to 40 young people. At the regional level, the Department of Labour, Social Affairs, and Families has initiated the Sostre 360º (360º Ceiling) project which aims to give individualised support to young people aged between 18 and 24 who are homeless or with inadequate housing, while also working to improve their autonomy in a shared residential setting. Throughout 2021, it is expected that a minimum of 140 young emigrants can be attended to around Catalonia irrespective of their administrative situation.

With regard to access to healthcare, most of the interviewees in this study did not complain of problems in access to health services and confirm good management of the health card. However, significant deficiencies are noted with regard to mental health care. While grave mental health problems can be referred to different services (for example the Mental Health Team for Homeless People, the Dar Chabab psychiatric team, the Transcultural Team at the Vall d’Hebron Hospital, etcetera), other problems such as stress, anxiety, depression, and the various kinds of malaise deriving from the pain of migration are not being treated transversally. This is a matter for concern of entities working with unaccompanied young migrants as they note that more than 90% suffer from some or other problem of mental health. The organisations interviewed for this study also detect barriers of access to sports activities outside the domain of leisure or recreation and hence to the physical and psychological benefits deriving from them.

With regard to measures aiming to strengthen social relations, it is important to mention the mentorship programmes, managed by the Generalitat and also such organisations as Punt de Referència, BarcelonActua, Migra Studium, and Servei Solidari, among others. A study recently published by the University of Girona (co-authored by Alarcón and Prieto-Flores 2021) draws attention to the connections that exist between the social support received by young emigrants in the host society, their mental health, and their chances of constructing new educational futures. According to this study, mentorship is not only a source of psychological wellbeing, but it also seems to have positive effects in educational expectations and aspirations. The mentors are essential thanks to the trust they inspire and also because they end up guiding the young people through the educational system and can therefore be fundamental in helping them decide what path they want to take.

Family foster care is also increasingly being encouraged as an alternative to institutional care. In the BarcelonActua family foster care project, after receiving training and signing a contract specifying the rules of coexistence, the family undertakes to foster the young person for a minimum of three months. The foundation participates by providing pocket money for the young person and following up every case by means of monthly meetings. As part of the Shock Plan that was approved in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, BarcelonActua also opened a reception facility for young former wards of state who are attended to by voluntary people of reference until they are taken in by a family in the city. In 2017, the Migra Studium Foundation inaugurated the “Xarxa d’Hospitalitat” (Hospitality Network) which promotes family fostering for migrants and refugees in general. At present, this network consists of 68 foster homes, which means that 65 adults and 8 minors can be fostered for a minimum of 4 months. On another level, with a view to promoting meeting spaces, BarcelonActua has launched the BACApp, a mobile phone app that enables volunteers to sign up for activities, many of which include unaccompanied young migrants.

In the case of prevention measures, and with regard to those accommodated in residential facilities, daily contact makes it possible to detect and prevent cases of criminalisation or victimisation. Nevertheless, progress needs to be made in cases of those who will soon be homeless and sleeping rough. In this latter case, according to the professionals we have interviewed, much of the responsibility is shouldered by the team of educators working in the streets of Barcelona and the Dar Chabab Day Centre. While teams working with these facilities identify and act upon situations of victimisation, detecting criminal conduct is a policing matter, which means that proper prevention rarely happens because, in other words, any action is often a posteriori. In the specific case of prevention of gender violence, the FEPA emancipation guide provides services for training and reporting violence. Then again, some reception entities—but only a few that are known so far—have now adopted a transversal stance on gender in the processes of providing protection for and attending to unaccompanied young migrants.

Regarding the matter of training professionals, the interviewees concur in remarking on deficient training of professionals and volunteers who are attending to this specific group. Since 2018, the Ramon Llull University has offered a master’s degree for training experts working in the area of unaccompanied children and young migrants. The Department of Labour, Social Affairs, and Families has also organised specific training activities for professionals in the public system for protection of children and young wards of the state as well as newcomers. Security agents, social work professionals, and staff of Citizen Attention Offices have also participated in training courses. For example, in 2019 new guidelines for action of the Barcelona Guardia Urbana (Metropolitan Police – GUB) were formulated and all agents of the GUB received training from specialist organisations of the city as part of the project of combatting the various forms of discrimination. As for professionals working in the organisations and volunteers, each entity selects and trains in keeping with its own requirements. Although it is not specifically a training resource, the FEPA emancipation guide provides information about benefits, procedures, rights and duties, services, and resources for professionals and also for young wards and former wards of the state.

As for measures taken with the host society in mind, in particular with regard to social conflict and hate speech, the conflict management services intervene in areas where unaccompanied young migrants are involved in neighbourhood conflicts. These services interview all the people concerned and, from a community perspective, try to find solutions for defusing the conflict without involving the police. The Barcelona Xarxa Antirumors (Anti-Rumours Network) has not yet launched a campaign specifically for unaccompanied young migrants, but it does share content about Islamophobia. The Office for Non-Discrimination (OND) is active in the area of awareness and supporting those who report such problems, working in coordination with the Prosecutors Office for Hate Crimes. More generally, the Barcelona Municipal Immigration Council (CMIB) has produced the manifesto “Per una Barcelona antiracista” (For an Anti-Racist Barcelona) with a view to achieving a more just and egalitarian city.

At the level of Catalonia, the FEPA campaign #uncallejónsinsalida (A Dead-End Alley) has sought to draw attention to the cul-de-sac situation of unaccompanied young migrants once they come of age. Moreover, the campaign has urged a change in immigration regulations in order to make it easier for them to join the labour market and to spare them from having to deal with sudden, inescapable situations of irregular status. The Sostre 360º project, which we have mentioned above, was also conceived as a way of responding to and minimising neighbourhood conflicts arising from situations of squatting, sleeping rough, or inadequate housing for unaccompanied young migrants. Since 2019, the EX-MENAS Barcelona association, which was created by former wards of the state and the Espai Migrant (Migrant Space) of the Raval neighbourhood, has been organising and participating in anti-racist demonstrations, and also activities in the social networks in order to make visible unaccompanied young migrants and prevent prejudice.

3. Conclusions and recommendations

As a result of analysis of policies and programmes carried out in Barcelona when dealing with situations of serious social exclusion (which, we repeat, is generated by structural factors) suffered by young migrants after they come of age, some significant progress has been made (sometimes in adverse circumstances and with large increases in the numbers of new arrivals), but there is still much to be done. The biggest effort has been made in the area of access to housing. A major effort has also been made (and even greater with the pandemic) to obtain specific resources for young homeless people who are sleeping rough. However, there are three domains where a lot of work still needs to be done: in education, going beyond basic, unregulated training; in employment, establishing a system of grants and incentives in addition to creating jobs for people of certain vulnerable profiles; and in mental health, making sure that the young people have access to mental health services from the very beginning, and also working to train educators in the field.

Much work is yet to be done, too, with regard to encouraging formal and informal social bonds, as well as prevention programmes. In the area of nurturing social relations, major progress has been made with mentorship programmes and foster families, but this needs to be consolidated as an essential part of reception programmes. Further progress also needs to be made with initiatives promoting meeting spaces for young people or groups of different origins. In the case of prevention measures, street educators and conflict management services are carrying out crucial work. However, anticipation is also necessary. In this regard, individualised follow-up must be carried out with people who are vulnerable to criminalisation or victimisation, and this work needs to be a coordinated effort involving the various agents concerned (educators, protection centres, juvenile prosecutors, outreach workers, health services, local and national police, and so on). Work also needs to be done with initiatives aiming to combat hate speech. This necessarily entails including the young people when countering rumours and creating alternative narratives.

In terms of recommendations resulting from our discussions with representatives from areas of the administration and social entities, we would highlight the following general issues that should be borne in mind:

- Regularisation: Access to documentation is essential, not only for assuring access to basic rights, but also as a necessary condition of social integration. Hence, all social entities have celebrated the recently (October 2021) announced reform of the Regulations of the Aliens Act whereby unaccompanied young immigrants can work after turning 16 and are not faced with sudden, unavoidable irregular status when they come of age or when trying to renew their documents. Clear and inclusive (territorially homogenous) criteria are also needed when regulations are applied, and to ensure that the procedures for obtaining a residence or work permit are the same for all provinces. Moreover, legal advice services must be improved by specialist professionals, and they must be sustained over time. All municipal councils should have the same registration policy in the municipal census (el padrón), independently of the legal status and residential situation of the young migrants. This is important because non-inclusion of this group of people has adverse effects not only on their rights but also in terms of local social coexistence.

- Multilevel governance: Only from multilevel governance will it be possible to offer a coherent response to the situation of these young people. This should be in the vertical sense, since jurisdictions are shared: from access to documentation (which is a jurisdiction at the state level), to guardianship of minors and young people (at the level of autonomous region), through to integration in the associative fabric and civil society (which, by definition, is at the local level). Any bad decision or policy at one of these levels will have effects on the others. In the horizontal sense, it is essential to understand that a coherent response requires integration and coordination of the various spheres of public policy, and also among the actors (public and non-public) involved.

- Support in deinstitutionalisation: Any process of deinstitutionalisation requires that support should be given. And this support cannot be partial, either in time (for a short period) or in the areas covered (with residential resources but, for example, with scant attention to social and employment aspects, or to mental health), or in the collectives themselves (leaving out one part, for example, because of lack of documentation, or not having spent enough time as minors under guardianship of a certain autonomous community). Moreover, it should be understood that this support in the process of deinstitutionalisation does not only include access to certain rights but also, and especially, providing more intensive support for cases of greater vulnerability. In this regard, whether the young people have been under guardianship or not, it is necessary to create specific resources and services for minors (children with behavioural problems) and older youngsters who are in highly complex situations owing to possible mental health disorders and/or risk dynamics (consumption of toxic substances, criminal conduct, etcetera) and who, as a result, have a significant impact in public space.

- General social services but not always: Although, as a general rule, it is important to provide standard access to public services, they should not end up being a dumping ground for a whole variety of highly vulnerable groups with specific needs. When specific resources fail or when they do not function properly because of lack of formal or legal recognition by the state, social services (frequently in the hands of local administrations) end up responding to a too diverse range of needs and also, as happens very often, when they are already working at full capacity and thus not capable of dealing with the whole group of people who need attention. For example, in the case of Barcelona, facilities for homeless people have ended up answering the needs of asylum seekers (who are waiting to enter the reception system or who, having passed through it, have had their applications denied); of migrants who have entered through the southern border; and of unaccompanied young migrants. Their needs, although common to all groups, must be addressed differently, just as the needs of people who traditionally turned to these services must also be dealt with differently.

- Promoting formal and informal social bonds: Formal and informal social bonds are essential in the integration process of these young people. In this regard, we have mentioned mentorship programmes, foster families, and other initiatives aimed at fostering relations with volunteers and other people of similar age groups. However, these programmes need solid support from the administration and other organisations. They must not be a means for outsourcing to civil society the costs of social support and deinstitutionalisation, for two reasons. First, they are the responsibility of the various branches of the administration and, second, studies of these programmes show that their effectiveness depends on solid support in terms of both general resources and specialist professionals.

- Prevention is crucial: Given the highly complex situation and vulnerability of some of the young people, prevention policies are essential. It is therefore vital: to improve the coordination between the entities and branches of the administration, for example in identifying the young people who will soon have to leave housing facilities and will therefore be homeless and sleeping rough, and those who are in serious situations of social exclusion; to help the young people to recognise possible situations in which they could be victims of abuse, as well as providing them with spaces for reporting such eventualities; and to promote programmes to aid the social integration of young people caught up in the juvenile justice system, serving sentences, and leaving prisons without any kind of support network and, in many cases, in an irregular administrative situation.

- Encouraging alternative narratives: The various forms of hate speech must not only be combatted (for example, from an anti-discrimination office) but it is also essential to forestall them by encouraging alternative narratives, which are constructed from different areas of the administration (for example, by promoting an anti-rumour network), as well as, and in particular, through spaces of social proximity. In other words, it is only by means of direct knowledge and personal experience of coexistence that it is possible to counter damaging stereotypes. Accordingly, programmes promoting mutual knowledge (for example, in secondary schools, recreational, cultural, and social associations, and neighbourhood activities) are very important. Moreover, it is necessary to give voice (always individual and always different) to each of the young people and make their stories known. In brief, it is essential to encourage new ways of seeing each other by creating spaces for meeting and exchange.

Bibliography

Alarcón, X. and Prieto-Flores, O. Informe sobre los impactos de las relaciones de mentoría en las condiciones de vida e inclusión social de jóvenes migrantes. Project funded by Recercaixa, 2021.

Federación de Entidades con Proyectos y Pisos Asistidos, Jóvenes en proceso de emancipación: análisis de resultados. Encuesta FEPA 2019. Barcelona:FEPA 2020

Keywords: young emigrants, reception system, diagnosis, Barcelona