Spanish integration policies according to the MIPEX Index

Since the outbreak of the so-called “refugee crisis”, Spain’s public and political debate on migration has been centred on asylum and refuge. This debate has come along with a specific focus centred on entry issues, namely border control and early reception. But what about next? Five years after the crisis outbreak, more than 100.000 people have received international protection and started to settle in Spain. What do these people face after arrival and initial reception? What about their long-term integration? From a public policy perspective, this gets to wider issues that go beyond entry and asylum and have to do with the overall system regulating migrant integration, namely integration policies. At the end of 2020, around 5.5 million foreigners live in Spain, over 11% of the population. Questioning integration policies not only implies reflecting on the situation of migrants and refugees living in Spain, it means reflecting on the present and, even more, on the future of Spanish society.

This paper takes stock of the current state of integration policies in Spain in terms of formal equality. It therefore evaluates the extent to which the framework that regulates the integration of immigrants in Spain guarantees their rights, opportunities and stability on an equal basis to the rest of the population. Integration policies are just one of the factors that affect the integration process, but they are key to establishing the normative framework of possibilities and limitations an immigrant encounters in the host society.

To perform this analysis, we have used data from the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), the most extensive and authoritative system of indicators on integration policies (Joint Research Center of the European Commission, 2017). 1 On a scale from 0 to 100, MIPEX assesses a state’s regulatory framework in relation to the main European and international standards on integration.2 MIPEX indicators evaluate: the de jure system of guaranteed rights for foreigners; the targeted regulations aimed at promoting their integration; and the security of their long-term legal status. MIPEX covers eight policy areas (mobility in the labour market, family reunification, education, political participation, long-term residence, access to nationality, anti‑discrimination and healthcare) in 52 countries between 2007 and 2019. The most recently published results assess the state of integration policies at the end of 2019.

This analytical tool gives us a privileged perspective on the state of integration policies in Spain, making them comparable with those of other countries, as well as examining their evolution over time. Without neglecting the importance of time as a factor, this article favours a synchronous comparative approach with the dual aim of: (i) identifying the strong and weak points of the Spanish regulatory framework in each policy area; and (ii) suggesting possible improvements, based on the experiences of other countries.

Integration policies in Spain, a comparative view

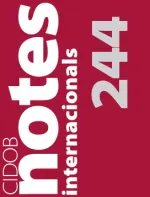

Evaluated as a whole and in comparison with international standards and according to the 0–100 MIPEX scale, Spanish integration policies score 60. This places them above the average for the European Union (50) and of OECD countries (56). The Spanish regulatory framework promotes a comprehensive approach to integration, with particular emphasis on the access to rights. When entering the labour market or requiring healthcare, a foreign person has fundamentally the same recognised legal protection as the rest of the Spanish population. However, the Spanish framework lacks targeted integration policies and provisions that ensure a stable pathway in the host society. This approach, which prioritises access to rights over more specific and long-term policies, reflects a broader trend in the European and global context (Figure 1).

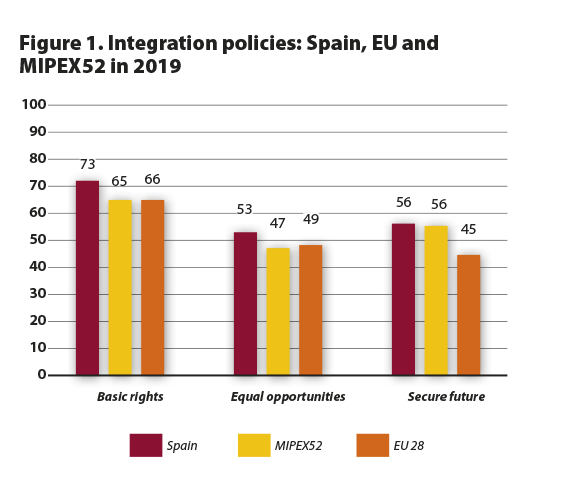

This general trend conceals substantial variation across the different policy areas. In most, the Spanish regulatory framework ensures more favourable conditions than those guaranteed by its European counterparts, especially with regard to access to healthcare and family reunification. On the other hand, in areas such as anti-discrimination and access to nationality it shows notable limitations (Figure 2).

Health

Scoring 81 out of 100, Spain stands out on healthcare, ranking fourth of the countries analysed by MIPEX in this field. Unlike most of the countries analysed, the Spanish framework guarantees de jure universal health access. The Royal Decree Law 7/2018, of July 27th 2018, on universal access to the National Health System, which legally establishes it, expressly mentions the need to guarantee the right of access to healthcare to the foreign population, as a particularly vulnerable group. In other national settings, access to health services and benefits is restricted to residents (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States). Other countries limit the range of services offered to the foreign population, as in the United Kingdom and Portugal. That said, the Spanish system continues to reveal major shortcomings and obstacles. Administrative barriers and a lack of ad hoc tools to better meet the health needs of migrants end up de facto limiting the right to health. Examples of these obstacles are the introduction of healthcare co-payments, which increase social inequalities when it comes to receiving health benefits; and a lack of homogenised access procedures, for example, regarding the differing regulations for entering the resident register. Ireland (85), on the contrary, not only ensures universal access to healthcare, but has placed the health of migrants and ethnic minorities high on the political agenda, reduced administrative barriers and increased investment in research on migrants’ health and medical needs.

Permanent residence

Permanent residence in a country is a key part of integration, as it grants the permanent right to hold rights: it opens the door to the creation of lasting employment, personal and family relations, and is a necessary condition for securing long-term, stable prospects in the destination country. In Spain, non-EU citizens have a favourable framework for acquiring permanent residence (75). Indeed, it is easier to acquire it in Spain than in other settings where, as well as the length of residence requirements (five years in Spain), knowledge of the language is needed (e.g. Germany and France) and/or a degree of economic means (e.g. Austria and Ireland). Unlike, for example, Argentina, Chile, Belgium and Australia, the residence permit in Spain provides automatic access to social security. However, the differences in more favourable and better articulated legal frameworks should be highlighted. Finland (96) and Brazil (96), for example, not only set their length of residence requirements below five years, their residence permits also benefit from more extensive and better developed regulatory protection. In Finland, the residence permit is automatically renewed, preventing delays from affecting the person’s administrative situation. Brazil allows the foreign person to be absent from the country for a period of over three years without that resulting in a breach of their length of stay requirements. In Spain, one (cumulative) year of absence is enough to forfeit the opportunity to apply for permanent residence. The rigidity of this normative provision often clashes with migrants’ desires to move and alternate stays in their countries of destination and origin.

Family reunification

Family reunification policies define and regulate the right to family unity in the context of international migration. According to MIPEX data, the Spanish legal framework in this area is slightly favourable (69), scoring 19 points above the EU average. While many states require longer periods (e.g. Denmark, France, Greece, Germany, Poland, Norway and the United Kingdom), Spain allows family reunification after one year of residence for the partner, parents, minors and dependent older children, and other relatives in comparable situations. The reunited person’s residence permit has the same renewal conditions (duration, renewal and associated rights) as their sponsor (the family member residing in Spain who has requested family reunification) and, unlike other countries (e.g. Denmark and Finland), Spain does not require language or integration tests to be passed. One of the key problems with the Spanish regulatory framework is that the reunited person must maintain the family bond for three years before they can obtain a permit independent of that of their sponsor. This provision subordinates the rights of the reunited person to the stability of their relationship with the family member they join. And it raises serious problems: for example, a female victim of gender-based violence could be forced to stay in a relationship so as not to lapse into irregularity. Other limitations pertain to access requirements. In Spain, only foreigners with sufficient financial resources, specifically those with a salary at least 150% of the IPREM and appropriate accommodation, can request family reunification. Finally, it is worth noting that the measure approved in September 2020 (Instruction of the General Directorate for Migration 8/2020) granting a long-term residence permit to parents where they have minor Spanish children represents an important step towards facilitating integration and promoting family stability for immigrants.

Mobility in the labour market

Labour integration policies are essential to facilitate the access of migrant men and women to the labour market and to foster their professional development in terms of training and specialisation. In terms of access to the labour market, the Spanish regulatory framework offers better conditions (67) than those guaranteed in the average EU country (52). In Spain, foreigners enjoy full access to the private sector and self-employment in equal conditions to the rest of the population. Equivalent access to public employment services and to the main channels of vocational training and study grants are also recognised. The main problems surround the recognition of educational qualifications and, once again, the lack of specific measures. In Portugal (94) the immigrant population benefits from exclusive labour market integration measures and other, even more targeted ones, for specific groups such as young people and migrant women. In Sweden (91), another exemplary country in this field, migrants face no administrative obstacles to obtain recognition for their educational and training qualifications, unlike in Spain. But guaranteeing access to the labour market is not enough to produce labour market mobility – the opportunity to choose stable, high-quality employment must also be created and Spanish labour integration policies are far from guaranteeing this. In Spain, only 27% of immigrants have a permanent contract and 58% earn less than the minimum wage (Iglesias et al., 2020).3

Anti-discrimination

With a score of 59, almost 20 points below the EU average (78), Spanish anti-discrimination policies show substantial shortcomings. In Spain, the victims of racial, ethnic and religious discrimination are protected by the law (Organic Law 4/2000 on the rights and freedoms of foreigners in Spain and their social Integration), but it is a protection that lacks concreteness and efficacy. This set of rules fails to cover all cases and all different forms of discrimination. It is a highly general legal framework in which everything fits, but which lacks the necessary effective protections, enforcement mechanisms and provisions to achieve equality in the access to and supply of goods. Most of the countries analysed have more specific and developed legislative frameworks in this field. They also usually have state bodies that defend equality and diversity, with mandates enshrined in the regulations to fight discrimination on the grounds of race, ethnicity, religion and nationality. Several countries offer excellent (100) examples in this regard: Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Finland, North Macedonia, Portugal and Sweden. As well as a dedicated body, all these countries have laws that cover all forms of discrimination (covering all cases and fields of application) and also have positive action measures that seek to compensate the disadvantages that immigrant groups suffer compared to the rest of the population.

Political participation

In the field of political participation, Spain scores significantly above (55) the European Union average (28) and above most OECD countries (45). In Spain, foreigners are permitted to join political parties, unlike a range of countries both within the EU (e.g. Poland, Slovenia and Bulgaria) and outside it (e.g. China, Russia and Mexico). However, Spain's relatively favourable score in the international context hides significant limitations in absolute terms. Spain restricts the electoral participation of non-EU residents to municipal elections and requires compliance with the residence requirement (legal and uninterrupted for at least five years). The scope of this right is further circumscribed by the principle of reciprocity, which restricts this possibility to EU nationals and citizens of countries with which Spain has a bilateral suffrage treaty (Bolivia, Cape Verde, Chile, Colombia, South Korea, Ecuador, Iceland, Trinidad and Tobago, Norway, New Zealand, Paraguay and Peru). Other crucial problems with political integration in Spain relate to the lack of public funding for immigrants’ associations and active information policies. Finland (95) offers interesting and promising proposals in this regard. It not only recognises foreigners’ right to vote in local elections without restrictions, but also encourages their political participation at the national, regional and municipal levels via public institutions and by offering direct (material and logistical) support to migrant associations.

Education

Spanish integration policies also fails the test when it comes to education (43). While it is true that education is a competence of the Autonomous Communities and their laws and policies in this matter are consequently left out of the MIPEX analysis, the Spanish national framework also displays major deficiencies compared to other countries. Beyond recognising that compulsory education is a right and a duty for foreigners under the age of 16, the lack of regulations specifically covering access to education and its conditions for immigrants impedes their educational pathway and harms them by comparison with the rest of the population. Regarding higher education, there is a lack of measures adjusted to the needs of the foreign population: for example, to facilitate language learning, prevent school dropout and promote access to university education. The United States (83) has implemented these types of measures for years. Spain also has significant limitations in terms of teacher training and, in general, when it comes to recognising diversity within the educational model. In Sweden (93) and Canada (86), the national curricula include respect for cultural diversity as a cross-cutting approach, while intercultural education is taught as a separate subject in the curriculum. Both countries also have targeted policies to favour the incorporation of migrants as teachers in both compulsory and higher education.

Access to nationality

In Spain, the system for accessing nationality has remained intact since its inception (Law 51/1982). It recognises jus sanguinis as a basic principle, prohibits dual nationality and establishes a general requirement of ten years of residence for naturalisation. Exceptions exist, permitting shorter terms (two years) and simpler procedures for Sephardic Jews, citizens of former colonies (the Ibero-American countries, Andorra, the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea and Portugal) and those who have obtained refugee status. This set of rules is considerably more restrictive (30) than in most EU (40) and OECD (50) countries. For other migrant groups, the ten-year residence requirement for Spanish nationality is prohibitive. This is the case, for example, for Chinese and Moroccan citizens – the largest groups affected in numerical terms. Since 2015, it has also been necessary to pass a language test (level A2) and an integration exam of constitutional and sociocultural knowledge of Spain to acquire nationality (Royal Decree 1004/2015, of 6th November). None of these procedures is free of charge, making the possession of sufficient financial resources another requirement in practice. Accessing nationality is a key stage in the long-term integration process. Many countries recognise this fact in their regulatory frameworks. Sweden (83) does not impose financial requirements, or language or integration tests for naturalisation. Argentina’s system (91), taken as a whole, is even more favourable, as it recognises jus soli, dual nationality and offers an accessible naturalisation path in terms of time (two years of residence) and economic requirements.

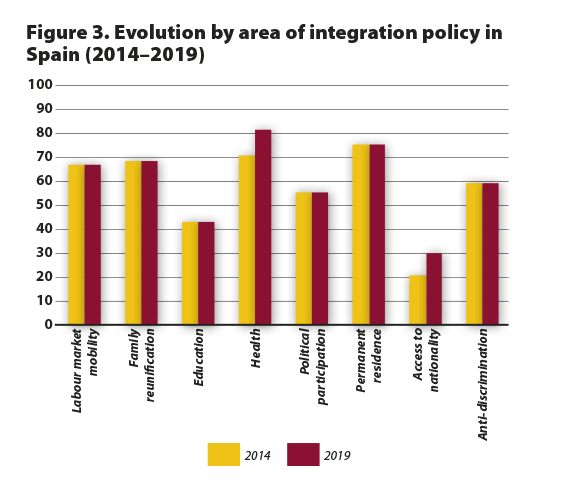

In this regard, it is worth highlighting the changes observed in two main areas. The first corresponds to the improvements in access to healthcare (+10). Royal Decree Law 7/2018 reinstated universal access to healthcare, guaranteeing health benefits to migrants regardless of their formal status. Resolving the limitations introduced by Royal Decree Law 16/2012, the 2018 reform brought Spain into line with the leading European countries in this area (e.g. Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Romania, Slovenia and Sweden). Other changes have also been made in access to nationality (+10). On the one hand, Law 19/2015 has reformed the old procedure in which the level of integration was assessed via interviews with local judges, and introduced standard tests of Spanish and knowledge of the country’s constitutional norms and culture. This has reduced the degree of arbitrariness in the process. On the other hand – and although this change has had hardly any bearing on migrant integration – the administrative procedure for processing nationality has been simplified (Royal Decree 1004/2015; Ministerial Order JUS/1625/2016; Resolution of 11th November 2015, of the Subsecretariat of the Ministry of Justice). Finally, it is worth mentioning the Royal Decree 893/2015, of October 2nd, which grants the Sephardic Jewish community more favourable naturalisation conditions and the advantage of maintaining dual nationality.

Conclusions

Taken as a whole, the Spanish regulatory framework on integration is above average for the European Union and the OECD. It is an advanced framework in terms of the formal access to rights, but presents significant limitations and restrictions when it comes to meeting the specific needs of migrants as a group and guaranteeing a stable long-term integration process.

The lack of actions tailored to the needs of foreigners hinders the integration process and often results in the de facto inability to exercise the rights recognised in law. In the health field and in the area of family reunification, Spanish policies are close to European and international standards. However, substantial problems persist in other areas, such as access to nationality. The notable lack of legislative activity since 2015 contrasts with a social reality that demands it, especially in certain aspects of integration. Anti-discrimination policies are one example. Genuine protection of diversity and safeguarding of the rights of immigrants will only be achieved by passing a specific law that covers all eventualities and proposes positive action measures. The first step in this direction is the revival of the proposed comprehensive bill for equal treatment and non-discrimination put forward in July 2019, which seems to be brought back up after the change of government and the COVID-19 crisis have displaced from the political agenda. It is also worth noting the lack of legislative progress on labour integration. Since 2015 the UN has reiterated its recommendation that the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers(ICRMW) be ratified. This remains a pending issue for the Spanish government if it intends to put an end to precariousness and promote the true economic integration of immigrants.

Room for improvement also remains in areas where progress has been observed. The 2018 health reform, for example, does not cover all the administrative aspects needed to make the right to health effectively exercisable; and it has failed to achieve its goal of reducing administrative barriers in order to provide a homogeneous system, as the pandemic has laid bare.

Beyond helping to identify strengths and – above all – weaknesses in Spain’s regulatory framework on integration, MIPEX's comparative perspective provides examples of best practices that offer concrete political solutions. Finland is paradigmatic in this sense, offering us examples in a range of areas, from education to nationality. Along with Sweden, Portugal and Canada, Finland shows the importance of the nexus between integration policies and the broader framework of public policies and the welfare state.

The scope of this study is, however, limited to the normative framework of integration "on paper". Integration policies, in a broad sense, also encompass other key dimensions that relate to the implementation phase, such as budget allocation and coordination mechanisms between actors. These elements, which lie beyond the MIPEX’s methodological scope, are especially relevant for the Spanish context, given its decentralised and multilevel integration governance model. The municipal divergences around the resident register and the access to rights that make up the integration system are a paradigmatic and prominent example of this methodological limitation. In this sense, this study seeks to be merely the first step in a deeper and more complete empirical reflection on the current state of integration policies in Spain.

Notes:

1- MIPEX methodology summary: “The highest standards are drawn from Council of Europe Conventions or European Union Directives. Where there are only minimum standards, European-wide policy recommendations are used”. For each answer, a set of options is provided with associated values (0–100, for example, 0-50-100). The maximum score of 100 is awarded when the policies comply with the strictest standards of equal treatment of nationals and foreigners (non-EU in the case of the European Union). The terms foreigners, non-EU and migrant are used interchangeably

2- Scipioni, M., Urso, G., Migration Policy Indexes, Joint Research Center (JRC), Ispra, 2017, JRC109400.

3- Juan Iglesias, Antonio Rua, Alberto Ares. Un Arraigo sobre el alambre, La Integración social de la población de origen inmigrante en España Fundación Foessa, Madrid, 2020.

Keywords: migration, integration, MIPEX, indicators, Spain, EU, OECD

E-ISSN: 2013-4428