Mediterranean Cities, the Urban Dimension of the European Neighborhood Policy

* This text includes work from the cooperation of CIDOB with the Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona (AMB) and the book “Wise Cities” in the Mediterranean? Challenges of Urban Sustainability

Relations between the European Union and its neighbors in the southern Mediterranean have come a long way since the launch of the Barcelona Process in 1995. Cooperation in the fields of economic, cultural exchange, and security cooperation has intensified. Cities are home to over two thirds of the European population, consume 80 percent of its energy, and account for 85 percent of its GDP. They are crucial for the localization processes of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the north of the Mediterranean urban growth is modest, flatlines, or has gone into reverse in the case of Italian cities, but on the southern shores of the Mediterranean societies are urbanizing rapidly with growth rates of most major cities between 1.5 percent and 2 percent per year. Not surprisingly European institutions increasingly include urban agendas in their foreign policies on the neighborhood. Cities play a growing role in international policy issues such as climate change mitigation, accommodation of migrants, and Track II diplomacy, yet their voice is sometimes subdued in the EU’s engagement with the southern and eastern Mediterranean. To intensify Euro-Mediterranean cooperation in a heterogeneous urban landscape across the Mediterranean divide, cities need to be brought on board. Avenues of municipal participation need to be strengthened within existing EU institutions, such as the European Committee of the Regions (CoR), but also via EU cooperation with international city networks such as the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (CEMR) and United Cities Local Governments (UCLG).

The European Neighborhood Policy in the Mediterranean and Its Urban Dimension

The European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), initially launched in 2004, was revised in 2011 and 2015 under the impression of the Arab spring uprising. After extensive stakeholder consultations its scope has been broadened. Security issues rank more prominently and interact closer with the policy fields of trade and development cooperation. Security is regarded as a necessary precondition for economic development. At the same time the EU hopes to strengthen security via economic development and improved governance. It aims at “stabilization of the region, in political, economic, and security related terms”. Interlinkages between development, security, and political stability are highlighted. Job creation for the burgeoning youth population is seen as an urgent priority alongside agricultural livelihoods and rural development. The four main areas of the revised ENP are: (1) good governance, democracy, rule of law and human rights; (2) economic development for stabilization; (3) security; and (4) migration and mobility. The dialogues on migration and security are key components of the revised ENP. The former seeks to “facilitate mobility, while discouraging irregular migration”. In this vein it tries to help the establishment of better education, health, and social protection systems for migrant communities in North Africa.The dialogue on security aims at combating terrorism and radicalization. This encompasses cooperation with civil society NGOs, but also security sector reforms in Lebanon and Jordan.

Most of the economic development and the political contestation that are associated with the core areas of the ENP happen in cities. The EU is increasingly aware of this aspect, not only when it comes to its own territory. In 2011 the European Commission argued in its Agenda for Change that civil society organizations and local authorities are crucial actors in development and need to be brought on board via participatory measures to ensure inclusive and sustainable growth. The ensuing dialogue with local actors led to the 2013 European Commission Communication on Empowering Local Authorities in partner countries. The EU prioritizes urban development in its ongoing budget period 2014-2020 and encourages Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) that turns traditional top-down development policy on its head. Instead of centralized technocratic plans, local communities are supposed to participate in the formulation of development goals in an attempt to leverage local social, environmental, and economic strengths. The ultimate goal is the creation of sustainable and inclusive growth and territorial cohesion. The EU has also given more funds to the URBACT III program, an exchange and learning program for sustainable urban development in Europe that seeks to tackle issues such as urban sprawl, and mobility, rural- urban interlinkages, energy efficiency, and support for disadvantaged neighborhoods.

The European Neighborhood Instrument has a budget of over EUR 15 billion for 2014-2020 and is the major vehicle for realizing the ENP policy goals, beside the bilateral Action Plans or Association Agendas between the EU and each ENP partner that come with conditionality tied to government and economic reform. This raises the question of how urban agendas find their ways into policy formulation and budget decisions and become an integral part of governance structures.

City Networks and the European Neighborhood Policy

The EU has a formal mechanism for participation of local actors in decision-making via the European Committee of the Regions (CoR). It is the European Union's assembly of regional and local representatives who are, however, appointed by the central governments of the respective member states. They are not chosen by municipal institutions. The European Commission, the Council of the EU, and the European Parliament have to consult CoR when drawing up legislation on matters concerning local and regional government. As such it only has a consultative function. However, it can bring municipal concerns to the European Court of Justice. The Euro-Mediterranean Regional and Local Assembly (ARLEM) is a permanent joint assembly that was established in 2010. It brings together members of CoR and municipal representatives from the south of the Mediterranean to discuss issues of mutual concern. It works on specific issues via commissions, such as the Commission for Sustainable Territorial Development that deals with cross-border cooperation, employment, and a sustainable urban agenda in the Mediterranean.

Beside the EU institution CoR there is a wide array of international city networks of varying geographic and thematic scopes. This diversity can be a fruitful pool of ideas and talents, but it can also be challenging for joint lobbying efforts because of overlaps and duplications.

Brussels based EUROCITIES represents over 140 large cities in Europe and Barcelona based Metropolis large cities globally, while Med Cities has a regional, not a global focus and primarily deals with technical cooperation, rather than political advocacy, just to mention a few. There are also specialized international networks such as the Bonn based ICLEI, Local Governments for Sustainability that organizes over 1,5000 cities, towns and regions on matters that are relevant for the sustainability aspects of the ENP. With a similar thematic focus, the C40 Global Climate Leadership Group and the 100 Resilient Cities project are philanthropic initiatives supported by US billionaire Mike Bloomberg and the Rockefeller Foundation, respectively. In contrast to the intercity associations of elected politicians they do not have a bottom up democratic mandate. Their structure can allow swift, well funded, and focused action, but also raises questions about accountability and legitimacy.

Barcelona based United Cities Local Governments is an attempt to bundle some of this municipal advocacy. Metropolis is in charge of its metropolitan section. As a global international organization UCLG gathers countries from the southern and northern shore of the Mediterranean. Among its seven geographic sections its European one is represented by the Council of European Municipalities and Regions and its Middle East and West Asia (MEWA) section represents southern Mediterranean municipalities. UCLG has a strategic partnership with the European Union since 2015, contributing to the Post-2015 Agenda and working towards Habitat III.

UCLG and its regional sections, such as CEMR, as well as Metropolis, ICLEI, and C40, are also cooperating under the umbrella of the Global Task Force of Local and Regional Governments (GTF) that was established in 2013 to bring a local and regional perspective to global challenges such as climate and resilience, financing for development, localizing global goals, and implementing the New Urban Agenda. Among the partners of the GTF are the European Commission, the UN, and other international institutions.

Thus, the diversity and heterogeneity of international city networks has been recognized as a challenge and cities work to increase cooperation across institutional divides. When the urban dimension of the ENP comes into play, further challenges arise with the considerable differences between southern and northern Mediterranean cities in terms of size, infrastructures, development, and level of autonomy.

Mediterranean Cities: a Mixed Bunch

Cities on the southern and northern shores of the Mediterranean belong to the oldest in the world and can draw on rich traditions of architecture, urban development, and municipal administration. Yet, there are fundamental differences between these cities. Mega cities like Istanbul and Cairo grapple with other challenges than medium sized cities along the Côte d’Azur that have higher per capita incomes and better infrastructure. Cities in the north of the Mediterranean also have stronger traditions of municipal self-governance and autonomy. In some cities of the southern Mediterranean mayors are more akin to appointed civil servants with limited fiscal space and decision-making power, while in many cities of the northern Mediterranean they are elected politicians with the freedom, funds, and mandate to formulate municipal initiatives of their own.

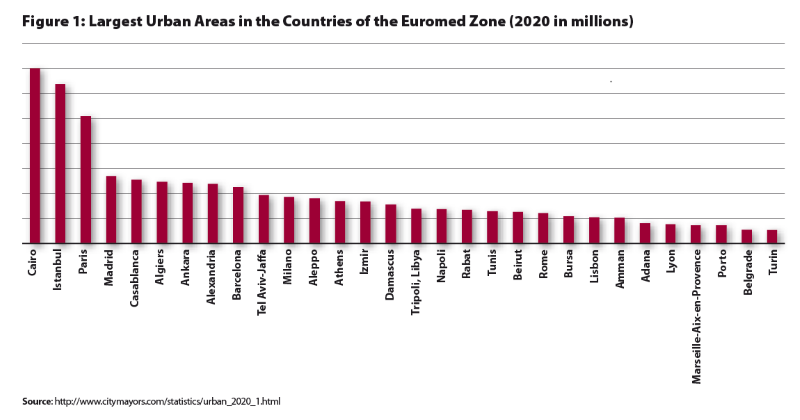

A look at a list of the 400 largest urban areas globally reveals that the largest ones in countries of the Mediterranean are in its southern part, led by Cairo and Istanbul (see Figure 1). Paris and Madrid follow, but are located inland and are not strictly Mediterranean cities. Turkey has the largest representation with four other urban areas beside Istanbul: Ankara, Izmir, Bursa, and Adana. Intermediary cities have accounted for much of the urban growth in the wider region, especially the Turkish corridor of Çanakkale-Izmir-Antalya-Gaziantep and the Maghreb coastal corridor between Sfax in Tunisia and Tétouan in Morocco. In contrast, population numbers in northern Mediterranean cities only show minimal population growth or trend sideways. Migration dynamics ward off natural population decline. Italian cities are an exception, as the populations of Rome, Naples, Milano, and Turin decrease between 0.33 percent and 0.56 percent each year. Like cities in Eastern Europe they are in demographic decline.

Source: http://www.citymayors.com/statistics/urban_2020_1.html

Some of the differences between northern and southern Mediterranean cities are embodied in architectural designs and urban morphologies. The medieval oriental city stresses privacy in ethnically segmented living areas with splendid courtyards, but sober and windowless facades. Meanwhile the public realm (e.g. mosque, souk) is controlled by autocratic rule. In contrast, the divide between public and private is not as clear-cut in cities in the north, which have more public spaces (e.g. forum, agora, town hall) as an expression of their traditions of constitutional government and municipal autonomy. In the 19th century colonial cities with right-angled street grid patterns were added to the urban geography in the southern Mediterranean, housing new centers of administration, commerce, and education. The post-war decades would see the sprawling expansion of suburbs and dormitory cities on both shores of the Mediterranean. This expansion has been often informal, sometimes followed by later legalization and connection with electricity grids and other public utilities.

In recent decades modern Dubai style urbanization has developed in the Gulf with vast, car centered traffic arteries, signature buildings, corporatized value chains, and gated communities in bespoke real estate developments, inspiring copycat projects of luxury real estate in Mediterranean cities such as Beirut, Cairo, or Tangier. Resource inefficiency of such agglomerations, limited public spaces that are commercialized and securitized, the spatial manifestations of social segregation and discontent, and the neglect and non-integration of architectural heritage have led to soul searching about the adequacy of such urbanization models and their underlying motivations. Cities struggle to integrate their architectural heritage in sustainable adaptation processes, oscillating between preservation romanticism and bulldozer runaway modernization. They are also facing the challenge of interacting more equitably and sustainably with their hinterlands from where they receive migrant populations and on which they rely for the provision of vital services.

Housing and urban networks are at the heart of the urban fabric. Real estate is a means to protect and legalize the monetary flows that are created by the urban economy and the flow of rents (location rent, sinecure, and monopoly rents) that are used by elites to foster political alliances in limited access systems as Dominique Lorraine has pointed out in a book on large cities in the southern Mediterranean, such as Cairo, Istanbul, Beirut, and Algiers. Cities in the southern Mediterranean have a large share of informal housing and struggle with poor quality of urban services, such as electricity, water, and waste disposal. Violence tends to be more prevalent than in rural settings. In limited access systems, the formal institutions serve people unequally and second rank institutions play a crucial role in the development of large projects. Self-organized informal neighborhood initiatives (e.g. for housing, waste disposal or cleaning) form a third pivot of urban governance in these cities.

It is a matter of debate whether the current urbanization drive in developing countries and emerging markets can be interpreted as a positive developmental process or not. In his 2010 book Arrival City, Doug Saunders argues that the Global South will become largely urbanized over the 21st century, undergoing processes that are similar to the urbanization history of the West in the 19th century. Now as then rural migrants are drawn by the economic pull factors of the “arrival city” on whose outskirts they settle. They gradually acquire urban equity and maintain a mutually beneficial relationship with their rural origins of migration by providing investments (e.g. second homes, tourism, agriculture) and helping newly arriving relatives to start out on their own, according to Saunders. In contrast, Mike Davies sees such sprawling agglomerations as symptoms of a “planet of slums”: dumping grounds for the permanently redundant of the post-industrial age, without real development perspective. Rather than pull factors he sees push factors as major causes of Third World urbanization, such as violent conflict and deterioration of state power in the rural peripheries in the wake of structural adjustment.

This debate cannot be decided here, yet it points again to considerable differences between cities in the north and south of the Mediterranean: whereas suburbanization and real estate speculation are major concerns in the north, rural-urban migration movements are a more pressing concern in the south. These differences also show in climate policies. Both the Paris agreement of 2015 and the Quito New Urban Agenda have stressed the importance of cities in climate change mitigation. Yet climate policies still play a subdued role in politics and policy formation in cities of the southern Mediterranean, as revenues from oil and gas exports and domestic energy subsidies play a central role in the social contract of local rentier and semi-rentier states as Eric Verdeil has pointed out. Energy exporters of the region are worried about low hydrocarbon prices and skyrocketing domestic demand that could compromise export capacity. The fiscal effects of high energy prices that can drain public coffers via growing energy subsidies is another concern, even more so for the net-importing countries of the region. In both cases the main focus remains production and tariffs of traditional hydrocarbons. States are reluctant to give up control over these issues while cities have no real autonomy and hardly figure in national energy debates. Dubai, Cairo, and Amman are the only MENA cities that are part of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership network. Thus the main driving forces for renewable energy transitions in the south are not climate policies, but the improved economics of solar panels and their possible contribution to diversification of domestic energy consumption. Such diversification is a predominant concern, as rolling blackouts have become a common occurrence in many cities and domestic hydrocarbon subsidies weigh on public finances.

With all their differences, Mediterranean cities share some of today’s most common urban challenges. Environmental degradation is a shared concern as are climate change, sea level rise, and growing social inequality. Gentrification and touristification are not only pressing issues for Barcelona and Venice; cities like Beirut and Rabat have grappled as well with displacements as a result of luxury real estate development. Beirut Madinati (Beirut my City) was a volunteer campaign during the municipal elections of 2016 that protested against corrupt politicians, power and water shortages, and a crisis in garbage disposal. Among its ten key demands were greenery and public spaces, community spaces and services, and affordable housing. If cities are exposed to negative side effects of economic globalization, they are also in a position to harvest some of its benefits. The fourth industrial revolution poses major threats and opportunities for how work and resource allocation is structured in society. Cities like Barcelona seek to foster new clusters of economic activity in the digital sphere. With the construction of a factory for electric cars by Chinese company BYD that is backed by US billionaire Warren Buffet, Tangier is well positioned to benefit from developments in this new key technology. International networks of cities relate to these common challenges of cities in the Mediterranean and can play roles as intermediaries in the ENP.

Initiatives, Projects, and Possible Avenues of Participation

United advocacy and lobbying efforts clearly need to be on top of the agenda for cities in the Mediterranean and beyond. Only if they pool interests and join forces they will be able to make themselves heard on a regional, national, and international level. “If mayors ruled the world” politics would be more pragmatic, solution oriented and less ideological the late Benjamin Barber argued in his famous book of the same title. Such enthusiasm must not overlook considerable limitations: cities are hardly without issues such as lack of accountability or inequality, they depend on national decision-making in crucial policy areas such as migration, trade and financing, and they have natural capacity limitations when it comes to foreign policy.

The Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments (GTF) is an important step forward to improve coordination and consultation between the major international networks of local governments and push their agendas in joint advocacy work. UCLG with its longer history and broad and decentralized organization structure is also in a good position to pool interests in its policy councils where its members deal with thematic issues such as the right to the city, multilevel governance, or resilient and sustainable cities. Its Global Observatory on Local Democracy and Decentralization (GOLD) gathers, analyzes, and shares information on decentralization and local governance across the world. Development cooperation ranks prominently among UCLG’s main preoccupations alongside participatory democracy, gender equality, culture, and local finances and self-government. It launches “waves of action” that include implementation of concrete measures, learning, advocacy, and monitoring and follow-up. In 2017-2019 its two waves of action have been the right to housing and migration. It is thus well positioned to inform ENP policy formation and could make itself heard more prominently, also because it already has a strategic relationship with the EU that encompasses institutional relations and advocacy, the provision of intelligence, the strengthening of local governance networks, and the fostering of cooperation and learning.

The Euro-Mediterranean Regional and Local Assembly is an avenue for increased participation that has already yielded concrete project results. ARLEM adopted a report on sustainable development that led to he First Ministerial Conference of the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) on sustainable urban development in Strasbourg (France) in November 2011. It provided UfM with a mandate to develop a guidance framework for sustainable development of Euro-Mediterranean cities and territories, develop related donor based projects, and commission a study about an Urban Agency for the Mediterranean.

In the wake of these UfM initiatives the Urban Projects Financing Initiative (UPFI) was established in 2013 to develop "sustainable and innovative urban projects which serve as best practice example and are potentially re-usable", with the support of international financial institutions and donors such as the Agence Française de Développement (AfD) and the European Investment Bank together with the European Commission and in association with other International Financial Institutions. The UPFI has now five UfM labeled advanced projects in North Giza (Egypt), Sfax-Taparura (Tunisia), Jericho (Palestine), Izmir (Turkey) and Bouregreg (Morocco). In total, up to 27 projects have been identified in nine Mediterranean partner countries, pointing to a considerable implementation gap. If completed, all projects would amount to investments of EUR 5 billion.

Conclusion

The revised ENP of 2015 moves security issues up the priority scale, but also keeps a close eye on economic development as a stabilizing factor in the southern and eastern Mediterranean. Much of this development is urban. Cities in the south of the Mediterranean continue to grow rapidly, while urban expansion on its northern shores has almost stopped or gone into reverse in the case of Italian cities. The growth has been particularly pronounced in intermediary cities. Improved rural-urban linkages and an upgrading of intermediary cities in urban planning agendas compared to overcrowded metropolitan areas are crucial aspects of urban planning in the southern Mediterranean. Rural migration flows and informal settlements loom large among its urban development challenges, while northern Mediterranean cities are more preoccupied with suburbanization and real estate speculation.

However there are many shared concerns such as environmental sustainability, growing social inequalities, and the provision of public services. City networks play a crucial role in assisting urban policy formulations within the ENP. They can help to create local ownership and the kind of Community-Led Local Development that the EU hopes to achieve. Initiatives like the Urban Projects Financing Initiative that was launched by the Union for the Mediterranean and others also engage in concrete projects.

There is an almost overwhelming diversity of international city networks. This raises questions about possible duplications that could compromise efficient and focused advocacy within the ENP process. At a minimum the involved networks will need to explore synergies and cooperation. To an extent they already do. The Global Task Force of Local and Regional Governments exists since 2013 as an umbrella organization. The Council of European Municipalities and Regions represents the European section of United Cities Local Governments, which in turn has a strategic partnership with the EU and has Metropolis as a member in charge for its metropolitan section. With its pan-Mediterranean and technical focus and strong representation of mid-sized cities Med Cities can provide important niche expertise and coordination. Such improved lobbying efficiency will be indispensable to inform the ENP process and its formal mechanisms of local participation via the European Committee of the Regions and the Euro-Mediterranean Regional and Local Assembly.

Keywords: cities, economic development, sustainable development, security, energy, climate change, governance, Mediterranean, European Neighborhood Policy, Euro-Mediterranean cooperation

E-ISSN: 2013-4428

D.L.: B-8439-2012