All that Glitters is not Gold: Unveiling Iran’s Economic Recovery

Iran has become a “hyped” country. Since the Joint Comprehension Plan of Action (JCPOA) – the technical name for the so-called Iran deal – was implemented in January 2016, much has been written about the economic potential of the country and its golden road ahead. It is present in every conversation, article and business meeting related to new markets and opportunities. Due to its “potential” to become the pivot for China, Central Asia and the Middle East, the government has been lavishly promoting the idea of a “promising” future for its citizens. And thus the last elections were a walk in the park for the Rouhani administration. Iranian society, drained from the never-ending economic embargo, had clutched at straws and unconditionally supported the craftsmen that are shaping a resolution.

Iran is currently enjoying a flourishing period of international activity with – almost – the rest of the world. Despite this past frosty decade in which Iran was turned away from the world’s main centres of power and networks, it is now reinstating itself as a relevant regional actor that also has an eye on becoming relevant in the international arena. Politically speaking, Iran has a finger in every pie, from the war in Syria to the Rohingya crisis, the country is currently embarked on a strategy of diversifying its relations with other countries as well as maintaining the ones forged during the tough years of international isolation. By contrast, in terms of its economic performance, things have been slower than expected. That is to say that the expected economic recovery is still not a reality – or the signs of it are not that clear despite the government promises and official discourse followed in recent years. Expectations among young Iranians are high and if not fulfilled in the medium term they might provoke frustration and potential unrest.

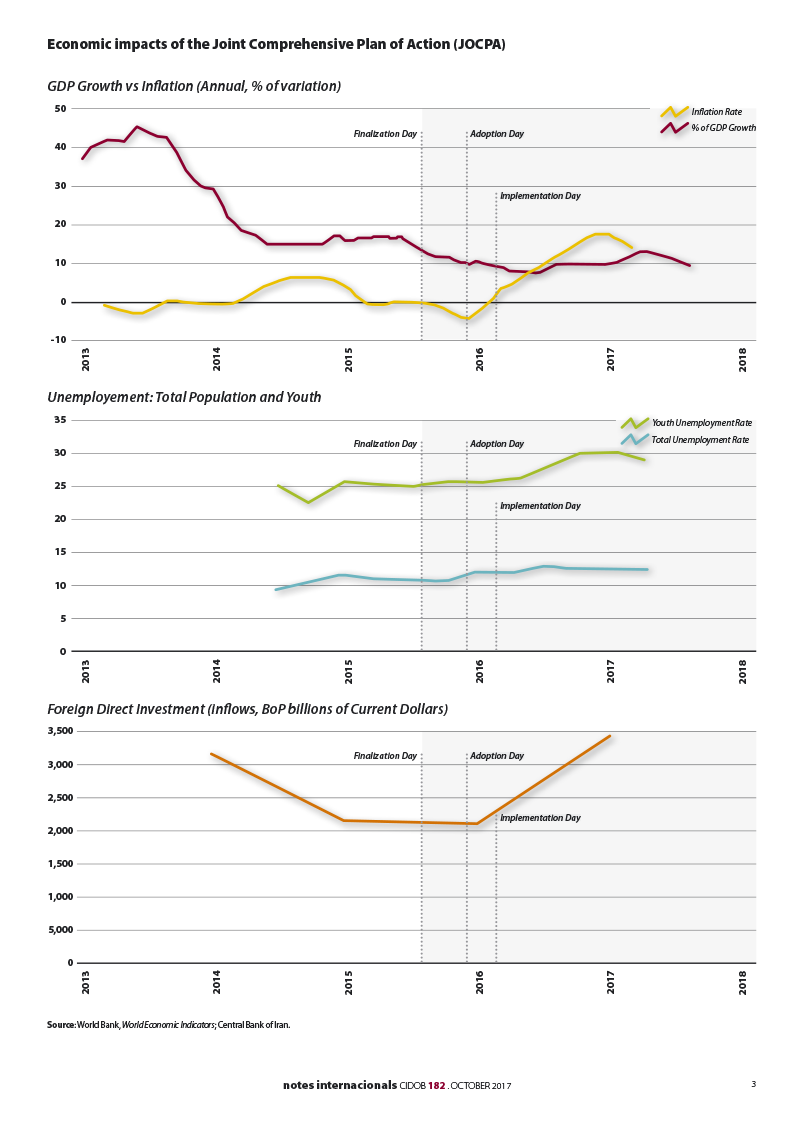

Looking closely at the latest figures published by the IMF, Iran’s GDP grew at 7.4% during the first semester of the 2016/2017 fiscal year, bouncing back from a long year in the negative. Forecasts predict a continuous positive trend in the upcoming years. However, when the oil sector is excluded from these calculations, the numbers are not that appealing. Real non-oil GDP growth for 2016/2017 languished at around 0.8%, which demonstrates the dependency of the Iranian economy on oil. The improvement of other important macroeconomic figures such as single-digit inflation (8.9%) after years of unsustainable, galloping inflation and the doubling of the current account balance to 6.3% are the Rouhani administration’s best presentation to the international markets. They have signalled to the markets that Iran is willing to commit to a sound and continuous economic improvement especially focused on stability and compliance with the macroeconomic standards of international institutions.

Do these numbers really entail an actual improvement in the country? Let’s be frank: not at all. Two important elements are missing from the mainstream (common) analysis of the Iranian economy: first of all, other relevant data show different information and reveal that the rigidities of the economy are not being confronted, or if they are, that aggregate solutions are not being put in place; and second, the nature of Iran’s economic structure is a key point for its future development.

All that glitters is not gold

The last Rouhani administration gained international and domestic credibility thanks to the JCPOA agreement and the alleged potential benefits for Iranian society. After four years in power and a year and a half since the JCPOA deal was implemented, the government boasts that it has performed reasonably well. As mentioned above, inflation has been tamed to manageable rates and the current account balance has also improved in recent months.

Before 2011, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows were around $4 billion per year, the majority of which were in the form of greenfield investment. Oil and gas and heavy industries attracted the greater part of them. This type of investment entails risks for the firms, but also means that there is a long-term commitment to the Islamic Republic, which is a green light for other companies already prowling the country.

According to government sources, for 2017 there will be $11.8 billion in FDI. Water and energy and heavy industries will be the main recipients of the inflow of capital. It seems that international confidence in the Iranian economy is real and is here to stay. However, when taking a closer look at the real dimension of this momentum, some things are pushed out of the picture.

Who is benefitting from this economic situation? The official unemployment rate has increased to 12.4% with an alarming 25.9% youth unemployment rate. Even though accessibility to data is not one of Iran’s strengths, according to the latest report released by the Statistical Centre of Iran (SCI), dating from 2014, the rise in inequality comes after four years of continuous decline and average per capita expenditure actually fell by 1.5%. In particular, the rate of decline was higher for lower income groups. That being said, the way Ahmadinejad managed to reduce inequality was a strategy of feast today, famine tomorrow which became a massive burden for the Rouhani administration once it got into power.

Diagnosis: bankache

Noticeable macroeconomic rigidities are challenging the common view about the policies implemented in recent years. As inflation is being reduced but interest rates remain high, issues are reaching the surface. During Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s two terms, populist measures were the daily bread. Policies such as low-cost housing and cash transfers were complemented by pressures on many banks to offer risky short-term loans to support some strategic sectors that a large share of his voters.

After years of careless economic policies ended and the economy started cooling down, many beneficiaries of those loans, mainly small and medium companies, are struggling to make the payments. Iranian banks’ non-performing assets account for 34% of total loans, with the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio at 10% one of the highest in the region. The high NPL rates are part of a bigger chunk of toxic assets – which account for 45% of the banks’ assets – built on immovable assets arising from the bursting of the housing bubble between 2005 and 2012 and the tremendous government debt. In a recent interview, Central Bank Governor Valiollah Seif stated that “banks should generally be lending 90% of the sum of deposits”.

The Central Bank of Iran (CBI) has stepped in to control the runaway situation. A year ago, the CBI set the official bank deposit interest rates at 15%, with an eye on bringing them more in line with current inflation rates of around 10%. However, since then reports of banks failing to comply with the new regulation have become worryingly frequent. This summer the CBI set September 2nd as the deadline for enforcing the new curtailed rates. However, the massive credit crunch suffocating the financial institutions will challenge the success of this measure.

In order to really tackle the problems arising from the financial system, the government will have to implement serious and sound reforms. First of all, to face this credit crunch means a serious rise in the money supply, thus, the government will have to take it carefully so as to avoid an uncontrolled outburst of capital flows and direct this increase to productive sectors of the economy to prevent new bubbles from materialising. In doing so, it will need the support of all the elements of the public sector. It is very important to work closely with the Majlis, Iran’s parliament, and that the next steps adopt a unified approach.

Secondly, a serious and deep restructuring of the financial system is extremely urgent. The clientelist nature of the Iranian banking system and the proliferation of small credit institutions under the administration of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, which currently account for 25% of the banking activity, are concerning the supervisory bodies. This Iranian style of crony capitalism has designed institutions officially or unofficially related to political, military and religious power axes that have been completely outside any regulatory oversight. However, dealing with these issues will enable the current government to get stuck into something extremely controversial in the country: the three-sector model economy.

The more the merrier?

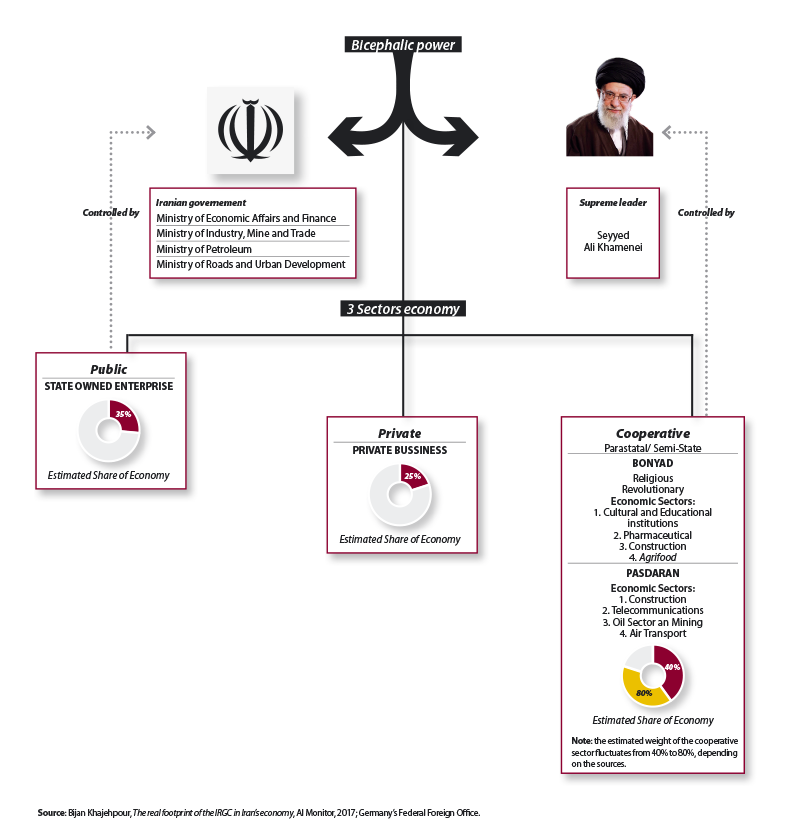

The Iranian economy has a very unusual structure. Article 44 of its Constitution states that “the economic system of the Islamic Republic of Iran is based on three sectors: state, cooperative, and private, and will be based on disciplined and correct planning”. The country is a unique hybrid political system of government where the circles of power are intertwined, but it does not imply that they work closely or that they follow one agenda.

The bicephalous nature of political power in Iran has been replicated in its economic power structure. Part of the economic structure is under state control and part is outside it. Even though the state does not supervise it, the part that works outside state control carries out its activities closely with it. Additionally, the state also offers benefits not applicable to the economic sector under state control.

Iran’s private sector (under state control) plays a very residual role, the public sector together with parastatal actors are the main sources of employment and economic activity in the country. There are two types of parastatal actors in the Iranian economy: the foundations (bonyad) and the Pasdaran organisation.

Bonyads can be divided into two different groups depending on the origin of their revenue. On one side we find the religious bonyads that obtain their revenues from the donations of pilgrims to religious places around the country, an example of those is Astan-e Qods. This organisation currently employs 19,000 people and has a diverse group of firms that runs from healthcare institutes to economic institutes and media outlets. The head of the organisation since 2016 is Ebrahim Raisi, the presidential candidate who ran against Rouhani in the most recent elections. On the other side are the revolutionary foundations, which were established in 1979 by Ruhollah Khomeini in order to manage the enterprises confiscated from people considered too close to the previous regime. Bonyads are completely independent from the state and are only accountable to the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, who is the head of state and the highest political and religious authority in the country.

The Pasdaran started its economic activity in 1989 under the country’s reconstruction (sazandegui) after the war with Iraq. Iran had serious infrastructure deficiencies and the Pasdaran stepped in with a construction company called Khatam al-Anbiya which would profit from its influence to obtain government contracts. Different administrations have awarded it with contracts ranging from the gas sector to the Tehran metro. It is said to have over 135,000 employees, 85% of whom are not part of the IRGC. It kept expanding through the creation of cooperatives that work in other sectors to the extent of being present in finance, communications, agriculture, import-export and culture. During the “privatisation programme” carried out by Ahmadinejad in his first term, they acquired controlling shares in many other businesses related to the pharma, telecommunications and automobile sectors, among others.

These organisations are benefiting from budget allocations, tax exemptions and credit lines from banks. They have promoted a solid relationship with the centres of power of the country through the placement of influential figures in strategic political positions that become their right-hand men in situ. Not only does this allow them to get their agenda through, it also offers inside information from the government, positioning these organisations at the level of the state: a state within the state. These two types of economic actors emerged from very distinct origins with clearly divergent aims. However, they have evolved into massive conglomerates that can be related to the development pattern of the South Korean chaebols in the 80s. That said, the case of Korea presents a worrying example of the collapse of a crony capitalism system ruling the country that allowed these holdings to steadily expand and diversify their businesses with the indulgence of the state until their collapse brought an economic crisis to Korea. Iran should take note of the lessons learned from massive corporations controlling strategic sectors of the economy and operating outside the state.

Rouhani’s second term: too many questions, too few answers

The rent-seeking nature of the Iranian economy makes it hard for the private sector to develop but the real hurdle comes from the three-sector economy. Rouhani had previously spoken of the intentions of his administration to promote entrepreneurship and private sector investment as a means of reactivating the economy; however, no plan has been put on the table. During his first term, Rouhani reaffirmed that corruption was a national security threat and declared his commitment to fighting it. Three years have passed since then and the country is placed at number 120 in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index. In the MENA region it is 11th, showing the little progress made by Rouhani’s administration and the existing contradictions between the official discourse and the economic reality.

Since the JCPOA agreement was signed and the partial lifting of the sanctions took place, millions of dollars have poured into the Iranian economy and almost every week Iranian newspapers update the citizens on the new business deals with foreign companies. But no significant change has been felt in the streets. The expected trickle-down effect from the FDI flows and the business partnerships with foreign firms has not materialised (yet).

A Reuters analysis revealed that since the deal was reached in July 2015, 90 of the 110 deals worth around $80 billion have been with businesses owned or controlled by Iranian state entities, including the Supreme Leader. The close relationship between the “cooperative sector” and the power structure of Iran has brought them a preferential position from which to profit from the revival of trade and investment and has pushed aside the opportunity to include new economic actors.

The willingness of the Rouhani administration to attract foreign investors and commitment to present the Islamic Republic as a reliable partner for the wary Western economies has driven the country’s economic policy towards market-oriented policies that do not (always) offer the adequate margin for redistribution or government spending in areas in need of stimulus. This further exacerbates the existing structural problems that are a consequence of the judicial and institutional limitations of the country.

With the IMF urging the country to implement serious banking reform, a monetary policy to keep reducing inflation, fiscal adjustment and some structural reforms in order to ease foreign capital entering the country, it is clear that there is room for important policies to make economic growth more inclusive and redistributive. Social inequality is a very powerful tool for creating unrest, which is the opposite of what economic development needs. During the last presidential elections, populist ideas came again to the centre of the speech, spurred by disillusionment and fatigue. This second term has been granted to Rouhani’s administration despite the anaemic improvement and the unfulfilled promises, because Iranians are still buying the “peace dividend” narrative from the nuclear deal. With a new US administration constantly threatening the agreement and Iranian society pushing for tangible outcomes, it will take more than strategic diplomacy for Rouhani to take the helm. The clock is ticking.

Keywords: Iran; Society; Economy; Financial System; Political, military and religious power

E-ISSN: 2013-4428

D.L.: B-8439-2012