Enhancing economic cooperation between EU and Maghreb countries: Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia

This piece benefited from the discussions of two foreign policy dialogues organised by CIDOB and CITPAX with the support of the State Secretariat for Global Spain of the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation. The first of those online meetings took place on February 19, 2021, around the topic of “Nearshoring in the Maghreb: priorities and impact on Spain”. The second one, entitled “Euro-Maghreb dialogue on nearshoring and post-COVID opportunities” took place on March 22.

Reshoring is not an expression most people had heard just over a year ago, but the interruption of European supply lines from Asia (essentially China) since the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in March 2020 have pushed the subject up the political agenda. Attention initially focused on pharmaceutical products, but other sectors are ripe for reappraisal, from the apparel industry to mechanical parts, IT and financial services.

Offshoring, which had its heyday a decade ago, consists in moving the production of parts of the value chain to lower-cost countries. Practised on a large scale between 1990 and 2010, that policy resulted in the US and the European Union losing tens of millions of jobs – indeed whole sectors of their industry – to the likes of China and other Asian countries. However, the shortage of certain health products (from masks to pharmaceutical goods) in the early months of the pandemic resulted in much soul searching about nearshoring, which consists in a company moving all or part of its value chain from Asian countries to its near abroad – which for the EU includes the Balkans, Turkey and the Maghreb.

As the costs of freight and Chinese labour rose, questions of security of supply came to the fore. The benefits of nearshoring also include reducing the environmental costs of transport, a factor which fits into the green transition – a priority for the European Commission (European Green Deal). Sharing similar time zones and a reduction of cultural discrepancies and language barriers are other factors to be taken into account.

Recent history of Europe–Mediterranean country cooperation

France’s links with Maghreb countries go back to colonial days and remain strong. In the late 1950s and early 1960s Italy conducted a very active policy of cooperation with Libya, Tunisia and Algeria, spurred on by Enrico Mattei, the founder of the state oil and gas company ENI, and again two decades later when Bettino Craxi was prime minister (1983–1987). The 5+5 initiative launched in Rome in 1990 was enlarged by Spain to include all south Mediterranean and EU countries after the initial success of the Israeli–Palestinian conference in Madrid in 1991. In a report to Commission president Romano Prodi in 2004, a prominent French political figure, Dominique Strauss-Kahn wrote: “no one can believe that, fifty years from now, a teacher explaining to his pupils the key groups of countries in the world which are coherent, would find a pencil fine enough to separate the two shores of the Strait of Gibraltar or the Bosphorus and thus the EU.” His insistence that the EU must cooperate with civil society and not with Arab dictators was the principle that underpinned the civil society meeting held in Barcelona in November 1995.

However, developing such links was always going to be more difficult than delocalising parts of its industry in a similar process to the one Germany promoted with former east European communist countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Industry was a much more powerful voice in German politics than in France, let alone Spain and Italy, and had enjoyed strong industrial links with east European countries before 1939. These countries allowed their norms and regulations to converge with those of the EU not only because of German industry’s outsourcing of part of its value chain but because they knew they had a chance of joining the EU after a reasonable delay. The loss of sovereignty implied by convergence was compensated by joining a large market and receiving substantial aid to modernise their economies.

Colonial economic links between the Latin countries and North Africa do not stand comparison. Maghreb countries were exploited by the former European colonial powers and after independence Tunisia and Algeria (but not Morocco) set about becoming economically self-sufficient. By 1990, it was clear this policy had failed, even in oil-rich Algeria, which like Tunisia is dominated by state companies and tight bureaucratic rule. In sharp contrast, Morocco decided after independence that the private sector should be the motor of the economy and that the country should insert itself fully into world trade. That policy did not deliver convincing results. Opinions today are divided, and many observers do not share the pessimism of others (Akesbi, 2017).

As the EU has never contemplated membership for Maghreb countries (as it has for Turkey), these countries feel the loss of sovereignty induced by convergence of norms and rules more keenly. Ever tighter EU visa rules have further upset public opinion in the Maghreb and, in the eyes of many there, make economic cooperation more difficult. This tightening was the result of EU fears about immigration flows from the region. As security and the fight against terrorism became paramount after 9/11, the Arab world came to be seen as a bed of nails: only a hammer could be used. The impression remains however that the two shores of the western Mediterranean are talking past one another despite the dense network of links the EU has knitted with civil society in the Maghreb. Scepticism is growing in the Maghreb while many in the EU express frustration – and even exasperation – at what they see as southern countries’ unwillingness to reform.

The EU’s new partnership offer

Reinforcing trade, investment and training links remains vital for the EU, as the Renewed Partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood Economic and Investment Plan for the Southern Neighbours policy document released by the Commission on February 9th 2021 makes clear. The plan does not offer a new agenda but adds two new chapters on the digital sector and green transitions to the traditional areas of cooperation on good governance, security and migration. The document also says the EU will support the reduction of non-tariff barriers, a major impediment to trade integration in the region, and puts forward the potential for trilateral cooperation to include Israel, Gulf and other Arab states. The investment plan’s Flagship 7 on digital transformation proposes concrete initiatives for Morocco, Tunisia and Israel. The aim is to deepen cooperation on cyber security and take advantage of digital technology in law enforcement with full respect for human rights and civil liberties. Given the human rights record of many of the region’s security and law enforcement agencies, such a policy will be highly problematic. In the view of many entrepreneurs and economists in the Maghreb, any cooperation with Israel is a very long shot.

The EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum, published in September 2020, also suggests linking vocational training, business-to-business networking, interregional value chains and circular migration to help skilled migrants wishing to move from one country to another or across the Mediterranean. In the Maghreb itself, the closed borders between Algeria and Morocco make this a non-starter but it might ease the movement of skilled workers from south to north.

Back in 2007, the policy of frontiers closed to investment, trade and regular flows of people was reckoned to cost Maghreb countries 2% in lost GDP growth annually. That figure was used by the World Bank, the IMF and at the conference on “El coste del no-Maghreb” organised in Madrid in May that same year. No recent estimates have been made but some observers believe the cost is higher today. The Maghreb is the least integrated region in the world. That as little as 2–3% of each country’s foreign trade is conducted with its neighbours acts as a major brake on their individual economic development and that of the broader region. It also hinders trade and investment links with the EU. In turn, this induces a broad lack of confidence in the future stability of the west Mediterranean region. The consequences also include the flight of capital and young people’s strong desire to migrate. However, in recent years and in sharp contrast to its immediate neighbours, Morocco is seeing the return of young, educated Moroccans who until a decade ago would not have found their country a congenial place to start a company. Morocco’s ranking in UN human development tables remains low but change is afoot.

The EU has spent little political capital to address this problem. The US once did but has other priorities today, a situation that suits the growing presence of Turkish and Chinese companies in the Maghreb. A generation ago, divisions among Maghreb countries mattered little to the EU, but China and Turkey’s growing economic and security presence in the Maghreb, Russia’s military comeback in Libya and its continued role as a major weapons supplier to Algeria give rise to concern in the EU and explain its desire to strengthen ties with Maghreb countries.

Is greater EU–Maghreb normative convergence possible?

Despite the difficulties, the need for convergence with EU norms and regulations remains a precondition for increased flows of EU foreign direct investment (FDI) into the Maghreb, whatever form that takes. For some economists, delocalisation, co-development and nearshoring are no more than semantic games. Morocco has made great strides to modernise its legislation to conform to EU norms, not least environmental ones. The more the Maghreb develops its economic relations with Chinese and Turkish companies, the more it will be in a position to resist EU pressure for convergence. All three countries may have lost their illusions of being treated as equals by the EU and actively attempt to diversify their economic partners but that does not detract from the reality that EU companies will continue to play a major role in the region for the foreseeable future.

One of the key prerequisites to a faster pace of convergence in norms and regulations between EU and Maghreb countries is freer movement of technicians and middle managers between the two shores and the right of professionals such as North African doctors, lawyers and other qualified people to set up shop in the EU. Instead, the Maghreb sees the EU “poach” its doctors, IT engineers and other skilled people if and when it suits its economic needs. This is impoverishing the region, rather than contributing to its prosperity.

Addressing this question is important, as it represents a major grievance from the south. The ambition of the Mediterranean becoming the “internal sea” once suggested by Mr Strauss‑Kahn does not seem to be on the agenda in 2021. It is worth noting that nowhere does the Commission’s document offer any discussion about inevitable trade-offs between pursuing objectives in the five priority areas. Furthermore, ten years after the Tunisian revolution, there is no debate as to whether earlier hopes that democracy, at least in its threadbare electoral form, might usher in reforms. Indeed, the contrary has happened. Having been so supportive of the Tunisia economy model’s capacity to deliver economic growth before 2011 and then of democracy to engineer reforms, many in Europe are perplexed about what to recommend.

An economic reality divorced from EU expectations

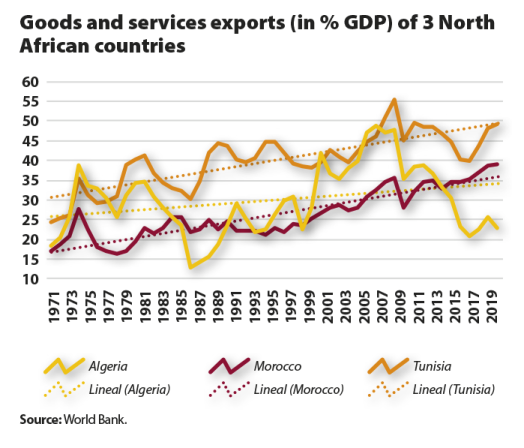

Tunisia and Morocco have been increasingly integrated in world value chains over the past half-century, but Algeria has travelled in the opposite direction since 2008.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows from the EU to the region started in 1972 after a landmark Tunisian law offered tax incentives for companies manufacturing for export. Initially for the textile sector, the incentives were later broadened to mechanical industries. By the turn of the century IT had joined the list. French, German and Italian companies make up the bulk of investment from abroad. The 1972 law followed the end of the “socialist” experiment of the 1960s, which had promoted self-sufficiency across many areas of economic activity. Since independence, Moroccan leaders had opted to give private industry and farming a lead role in economic affairs and to insert the country into international trade networks. This helped achieve steady economic growth and diversification but failed to reduce income and regional disparities, which the king has acknowledged (Akesbi, 2020).

Unlike its immediate neighbours, Algeria’s economy has been oil and gas-based since it became independent in 1962. In the decade that followed, Algeria nationalised foreign oil and gas interests and laid the foundation of state steel, mechanical and plastics industries which by the 1980s and however haltingly opened the door to private entrepreneurs in certain sectors such as pharmaceuticals, mechanical spare parts and plastics. Foreign investment was liberalised in 1991 and quickly attracted projects with major companies across the world. The liberalisation of the oil and gas sector followed, which opened the door to joint ventures worth billions of dollars. They boosted the exploration, production and export of oil and gas over the next two decades. The liberalisation in other sectors was reversed in the 1990s and never restored. Algeria is less inserted in international value chains today than 30 years ago. After 2010, more nationalistic policies led many foreign oil companies to exit Algeria, whose oil and gas production is stagnating. Sonatrach’s incapacity to act as a swing exporter of gas to Spain and Italy during the cold peak of last winter and its decision, for technical reasons, to cut off gas flows to Spain completely for a few hours on January 7th 2021 have seriously damaged the reputation of a once proud company.

Political uncertainty in Tunisia has since 2011 made foreign investors more cautious. In Morocco, joint ventures have usually focused on major mechanical plants and textiles, notably in the free zone of Tangiers. But the policy of major infrastructure investment over the past generation has probably been overdone there was no need for a fast TGV line between Tangier and Casablanca where the bulk of the ticket price is state-subsidised to make it accessible to middle-class travellers.

In all three countries, private companies depend closely on their relations with the state and practice a form of crony capitalism. It took the revolt of 2011 in Tunisia for that country’s major foreign partners to appreciate how far economic reality was divorced from the model roles imposed on the country by its major international partners as part of Africa (Davos) and the Arab world (World Bank and EU). By 2014, in a report which offers a rare act of contrition the World Bank ate humble pie. The Hirak revolt in Morocco in 2016–2017 showed the limits of the Moroccan economic development policies some in the EU are tempted to offer as a template to its neighbours.

Which sectors attract investment?

Tunisia

Until 2011, the country enjoyed a stable macroeconomic climate. Transport accessibility was reasonably good and the pool of skilled workers attractive, as was the lifestyle. The legal and fiscal rules were not too cumbersome for foreign companies, which worked mostly in the offshore sector.

Four sectors offer ample opportunities for joint ventures with and offshoring by EU companies: food processing; renewable energy; generic pharmaceuticals and IT. Where the first is concerned, European companies are very active in the olive oil and dates sectors. Tunisian production of olive oil has trebled since 2000, with ever greater quantities of high quality biological olive oil being exported across the world. Other niche farm products like dates, almonds, pistachios and eucalyptus oil are being developed. As water resources are scarce, olive oil trees offer the advantage of preventing erosion in semi-desert regions and of being labour intensive. One sector crying out for development is fish farming in the waters off the country’s east coast. Renewable energy is another very promising sector. Tunisia has modest reserves of oil and natural gas, but in combination with solar energy the industry could support multiple economic activities. Granting Tunisia green partner labels makes sense for the EU. Finally, Tunisia has a small but thriving pharmaceutical sector – notably for generic products – as it benefits from the work of many good engineers and technicians.

The sober truth today is that foreign companies are leaving Tunisia and there is little hope of change until the political crisis is solved.

Algeria

Abundant cheap energy, vast resources of renewable energy, a reasonably well-educated workforce and greater individual purchasing power should offer Algeria important advantages in attracting FDI. The value of the domestic market in medicines combined with a fast-growing pharmaceutical industry should bring opportunities for reshoring. In this sector a variety of state, domestic and foreign private companies have enabled local production to cover 60% of medicines needed today, compared with 10% a decade ago.

Over 160,000 kilometres of fibre optic cables have been laid in Africa’s largest country and the penetration rate of mobile telephones is 106%; 35 million Algerians are connected to the internet and 22 million have a Facebook account. Three companies share the mobile telephone market and 4G covers the whole country. But IT only accounts for 4% of GDP at present. These three sectors are unlikely to offer opportunities for FDI or nearshoring if Algeria’s management model is not fundamentally altered. The energy sector is in a shamble as a result of 20 years of bad management, corruption and lack of investment. In the absence of economic reforms which allow private and state sector companies to trade more easily with their foreign peers, Algeria will remain a country whose potential is unrealised.

Morocco

Morocco offers many of the prerequisites for FDI. Its workforce remains underqualified, but things are changing. Its middle class is growing, while its equivalents in Algeria and Tunisia are shrinking. Its policy of promoting itself as an African hub, buttressed by the growing sophistication of the Casablanca Finance Centre and a very modern TechnoPark in the same city hold promise. In its state phosphate company, OCP, and leading banks the country has players of international stature which can project the kingdom’s international interests.

In private, Moroccan entrepreneurs agree that their lack of access to the Algerian market remains a major handicap. Traditional bonds of history, language and taste – not to mention sheer proximity – make Algeria familiar despite the political problems of recent years. But over time they have diversified their partners and any opening up of the Algerian market is a pipe dream today.

The key sectors where nearshoring has been successful are the garment and automotive sectors, but what happens after COVID-19 is anybody’s guess. The automotive sector has become the country’s leading exporter, with revenues of $10.5bn in 2019 – although more than half of that value is imported. The sector represents a quarter of Morocco’s exports, employs 148,000 people directly and has a 40% local integration rate. Around 80% of the vehicles are destined for European markets, mostly France, Spain and Italy. What happens if these countries only recover slowly in the years ahead (Akesbi, 2018)? Finally, the country’s renewable energy policy has been ambitious and has already induced investment from China, from Siemens to make wind turbine blades, and from a Franco-Japanese consortium to build a wind farm in Taza region. The potential for EU companies is great.

Future challenges

While Morocco has pursued a consistent policy of attracting foreign capital and diversifying its partners across the world since 2000, Tunisia has failed to follow suit and is today totally beholden to a political crisis with no end in sight. Its trade and investment patterns tie it to the EU more closely than Morocco, which faces the challenge of spreading wealth more equitably across the country (the Hirak protest movement of 2015 in the north were an expression of frustration from a poor region). Morocco has been politically stable for two decades and its economic policies predictable, but they have failed to produce many jobs, let alone reduce social inequalities.

Algeria’s political future is less predictable today than at any time in the last 30 years. As its hard currency reserves dwindle and its politics remain dominated by the military – who may not even appreciate the depth of the coming macro-economic crisis – and the security services, whose sole purpose is to control and restrain ties with abroad, Algeria’s future hangs in the balance. Hirak, which convulsed Algeria in 2019, will not go away, however weakened it may be today.

The high hopes that the 2011 revolution gave rise to in Tunisia were exaggerated from the start. Corruption has been democratised while social and regional inequalities run deeper than ever. If Tunisia is forced to reschedule its foreign debt, it may act as a wake-up call. If the political stalemate persists a key question is whether the EU and the World Bank will continue to support Tunisia financially. Another question is how the political class and the people (who unlike in Algeria and Morocco have a voice) will react if the IMF steps in.

Many North Africans feel the EU has never treated them as equals but essentially as commercial partners. Scepticism in southern rim countries is often mirrored in the EU by a sense of frustration – not to say exasperation – that did not exist a decade ago. Maybe a note of cautious optimism is in keeping: both partners are growing up. The high flow vocabulary of the Barcelona Process has given way to a more mature conversation. What is not in doubt is that all three North African states are diversifying their economic partners. Yet, the long-standing ties of history symbolised by the presence of millions of EU citizens of North African origin and the reality that European companies will continue to play an important role in countries which still conduct more than half their foreign trade with EU countries mean Europe will never be able to ignore its southern near abroad.

References

Akesbi, Najib. “Economie politique, et politiques économiques du Maroc in Economie politique du Maroc, Ouvrage collectif”, Revue Marocaine des Sciences Politiques et Sociales, Hors-série, vol. XIV, April 2017, pp. 49–111.

Akesbi, Najib. “Un «modèle » en crise face à « la crise ». La pandémie de la Covid-19, un moment de vérité pour le pouvoir”, Revue Confluences Méditerranée, no. 114, Autumn 2020, IREMMO, L’Harmattan.

Akesbi, Najib. “Pourquoi et comment l’économie marocaine s’installe sous le ‘plafond de verre’”, News Hebdo, Hors Série, no. 36, December 2018.

Keywords: Economic cooperation, EU, Maghreb, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Covid-19, FDI

E-ISSN: 2013-4428